Find anything you save across the site in your account

What Could Tip the Balance in the War in Ukraine?

In 2024, the most decisive fight may also be the least visible: Russia and Ukraine will spend the next twelve months in a race to reconstitute and resupply their forces.

By Joshua Yaffa

On December 29th, Russia fired more than a hundred and fifty missiles and drones on cities and towns across Ukraine, killing more than thirty people in Kyiv alone, the largest number dead in the capital in a single day since Russia’s invasion nearly two years ago. The first days of 2024 brought more of the same: day after day of aerial bombardment, with the seeming aim of weakening Ukraine’s air defenses and targeting facilities that produce long-range weapons. This year is likely to be marked by exchanges of missile and rocket fire rather than dramatic, large-scale maneuver warfare. But the most decisive fight may also be the least immediately visible: Russia and Ukraine will spend the next twelve months in a race to determine which side can better reconstitute and resupply its forces, in terms of not only personnel but also shells, rockets, and drones.

In other words, the war may not be won outright this year, but the conditions for victory may well be set in motion. If Western backers provide necessary arms, training, and financing to Ukraine, its military may emerge, by next year, with the upper hand. But such an outcome is far from assured. “The West is on a trajectory to end up losing this war through sheer complacency,” Jack Watling, a researcher of land warfare at the Royal United Services Institute, told me. Watling has made more than a dozen research trips to Ukraine since the start of the invasion. “I’m not making a prediction,” he told me. “Rather, it’s a choice—Western countries have agency.”

Ukraine’s counter-offensive , which began in June before fizzling out in the fall, failed to capture any significant territory, let alone come close to reaching the Sea of Azov, which would have put pressure on Russia’s control of Crimea. In fact, according to an analysis from the Times , as of September, Russia controlled two hundred square miles more territory in Ukraine compared with the start of 2023. In Western capitals, this disappointment kicked off a round of finger-pointing, distress, and pessimism. Republicans in Washington had been looking for such a reason to question the merit of further U.S. aid to Ukraine. Last month, the House Speaker, Mike Johnson, after meeting with Ukraine’s President, Volodymyr Zelensky , said, “What the Biden Administration seems to be asking for is billions of additional dollars with no appropriate oversight, no clear strategy to win, and with none of the answers that I think the American people are owed.”

According to a recent report in the Washington Post , there have been frustrations on both sides: U.S. officials judged their counterparts in Ukraine as waging a delayed and inefficient campaign unlikely to yield maximal results. Ukrainian armed forces, meanwhile, have felt that they are expected to fight like the U.S. military without being provided with the full capabilities that the U.S. military possesses in the field. In an interview with The Economist last November, Valerii Zaluzhnyi, the commander-in-chief of the Ukrainian armed forces, admitted that the war has reached a stalemate, saying “there will most likely be no deep and beautiful breakthrough.” But, he argued, only a significant change in the war’s technological balance could tip the fighting decisively toward one side. For Ukraine, that includes airpower, both fighter jets and drones; electronic-warfare capability to counter Russian jamming; and counter-battery fire to locate and target Russian artillery systems.

“Ukraine’s military options were limited not only by what the West would provide but also by political choices,” Michael Kofman, an expert in the Russian and Ukrainian militaries at the Carnegie Endowment, said. For example, the Zelensky administration made Bakhmut a politically symbolic battle, keeping Ukrainian units fighting there throughout the spring and summer, which meant that many of the country’s most capable and battle-hardened troops were unable to take part in operations elsewhere. Ukraine settled on a strategy for an offensive waged on three axes at once, hoping to exhaust Russian reserve units. But the result was to further spread out forces and artillery. Offensive operations in the south, the most important front, were conducted by more inexperienced troops, fresh from training. When the initial assault failed, Ukraine switched to attacks by smaller units, which preserved lives and equipment, but did not lead to a larger breakthrough. “Ukraine didn’t have any easy options,” Kofman said. “But the three-pronged offensive did not deliver.”

Whatever the causes, the failure of the offensive created a number of problems for Ukraine. Russian forces may hold certain advantages, especially in terms of matériel, at the start of the year, Kofman said, but none of them look particularly decisive on their own. More important are unity, patience, and determination among those Western states supporting Ukraine’s war effort. “When your ability to continue fighting is so dependent on outside support, you also depend on the expectations and belief—or not—those same outside powers have in your path to victory,” Kofman told me.

The danger for Ukraine is that Western pessimism becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Mykola Bielieskov, a defense analyst at the National Institute for Strategic Studies, in Kyiv, said, “Skeptics in the West were provided with a very powerful argument: where is the guarantee that if we provide another sixty billion”—the amount that President Joe Biden is asking Congress to approve—“the result will be any different?”

The Kremlin, meanwhile, used 2023 to reorient the Russian economy around the war effort, pumping billions into arms production and related industries. Defense spending makes up nearly a third of the state budget for this year, during which Russian factories will produce as many as three million shells, a larger number than what would come from the U.S. and Europe combined. Watling pointed out the irony of Russia, an economy the size of Italy’s, outproducing the entirety of NATO in terms of artillery ammunition. Last year, Ukraine largely fought the war with munitions produced before the start of Russia’s invasion. “This year,” Bielieskov said, “is when we will begin to really feel the effect of decisions not taken earlier.”

Watling recalled meeting with defense ministries of NATO states as far back as the summer of 2022. “They asked me, ‘What does Ukraine need?’ ” Watling relayed the rough numbers in terms of troops and ammunition. As he tells it, he had another round of meetings this winter: “I told them, ‘We had this same conversation more than a year ago. The numbers haven’t changed. We’ve only lost time.’ ” By his estimate, last summer, Ukraine was firing seven thousand shells a day, and Russia was firing five thousand. Today, that ratio has swung dramatically in the opposite direction, Russia firing ten thousand shells for every two thousand launched by Ukraine. “The failure to translate rhetoric into action has a body count attached to it,” he told me.

At a recent Kremlin ceremony, Vladimir Putin appeared as sanguine and self-assured as he had since the start of the war, smiling with a glass of champagne in hand. Ukraine produces virtually no weapons of its own, he declared, and has “no future.” “But,” he added, “we do.”

“Putin can draw a certain line,” Tatiana Stanovaya, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center, told me. “In Putin’s understanding, the counter-offensive has failed, and the West won’t be able to provide the level of military aid that would fundamentally change the situation on the front going forward.” A period of uncertainty, going back to the unravelling of Russia’s initial invasion plans in 2022, appears to have ended, and one of stability has begun. All Russia has to do now is wait. “Putin thought all along that support for Ukraine was temporal and that he would outlast it,” a U.S. defense official told me.

Putin, then, isn’t entirely wrong to feel a renewed sense of confidence at the start of the year. And, if Russia can resist the temptation to waste lives and equipment in a winter offensive, its defensive positions look stable. But that may prove unlikely. “Our generals may well mistake the ability to defend with an opportunity to go on the attack yet again,” a defense source in Moscow told me. “The results of such an action are predictable.” (The source returned to an oft-repeated axiom: “Russia is never as weak as may appear, but it’s not as strong, either.”)

Fundamentally, Putin’s political goals for Ukraine remain as grandiose as ever. “In his mind, he really doesn’t want to take Kyiv by force,” Stanovaya told me. “He wants them to give up, to fall to their knees.” In other words, regime change, with a pro-Russian government in Kyiv not because Russian tanks installed it there but, rather, because modern Ukraine failed from within and could no longer resist Russia’s imperial dominion. “This was never about territory for him,” Stanovaya said. “He doesn’t care where the borders are drawn. If Ukraine is friendly, it doesn’t matter what territory formally belongs to whom—it’s all our land, in our zone.”

But, if Ukraine remains, in Putin’s terminology, “anti-Russia,” then it must be injured and weakened, one strike at a time. This explains the existence of two seemingly contradictory phenomena: Putin’s interest, as reported by the Times , in negotiating a ceasefire that would effectively freeze Russia’s current positions, and the unprecedented aerial bombardment of recent days. He’d prefer the former, but the latter is a way to demonstrate the cost of not making a deal on Russia’s terms. “Putin believes that not only is his preferred outcome achievable but that it is inevitable, and must be realized as swiftly as possible,” Stanovaya said. Entreaties about a ceasefire may be an attempt by Putin to lead Western politicians to question the necessity of further arms transfers to Ukraine.

After all, as Putin has always seen it, his real interlocutor is not the government in Kyiv but its Western backers, the U.S. most of all. Stanovaya encapsulated the Russian leader’s appeal for the coming year: “Either you abandon your support of Ukraine and reach a deal with us, or we take Ukraine anyway, and destroy a lot of lives and billions in your military equipment in the process.” As for the West, Watling said, “We’re really running down the clock.” ♦

New Yorker Favorites

The day the dinosaurs died .

What if you started itching— and couldn’t stop ?

How a notorious gangster was exposed by his own sister .

Woodstock was overrated .

Diana Nyad’s hundred-and-eleven-mile swim .

Photo Booth: Deana Lawson’s hyper-staged portraits of Black love .

Fiction by Roald Dahl: “The Landlady”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Susan B. Glasser

By The New Yorker

By Michael Schulman

By Dexter Filkins

Things you buy through our links may earn Vox Media a commission.

How Ukraine’s Counteroffensive Might End

Ukraine had high hopes for its long-anticipated counteroffensive , the goal of which is to reclaim territory Russia seized in the country’s south and east last year (as well as Crimea, taken in 2014) and force Vladimir Putin into a weak negotiating position. And although the country’s forces have made some promising recent gains , the operation has thus far been a deadly and demoralizing slog. Ukrainian soldiers have run up against vast minefields and other elaborate Russian defenses and have been able to make only slow progress, at a steep cost in men and equipment. With the limited time before the onset of the fall mud season, what can Ukraine realistically accomplish? For perspective on that question, I spoke with John Nagl, a former lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army who has written extensively about counterinsurgency and is now a professor of warfighting studies at U.S. Army War College. (Nagl made clear that his views on the war did not reflect those of the army, or the Department of Defense.)

I was reading a Wall Street Journal article you were recently quoted in, and its premise was that the West had not properly trained or equipped Ukrainian forces ahead of Ukraine’s big counteroffensive, which hasn’t been hitting its goals. That was mid-to-late July; have things changed much since then? Not a lot. The defensive is the stronger form of war, as we teach at places like the Army War College. You should have a three-to-one advantage if you’re going to succeed on the offense. Force ratios are really tough to determine in this war, because the Ukrainians have been really closed-lipped about their capabilities and the forces they have, but it’s probably closer to a one-to-one. You try to achieve local superiority, but that’s hard to do because the other side is also looking to create a counteroffensive. In fact, the Russians have done that in the northeast of the country.

The Ukrainians aren’t just lacking air power and air superiority, without which the United States would not attempt a deliberate attack; they also lack the force ratios. They lack expertise in combined arms warfare. They probably don’t have sufficient armor. They’re running short on artillery. They don’t have the long-range fires we’d like to have. In addition to close air support at the point of penetration, you’d like to have the ability to interdict deep with deep fires, either with air power or with really long-range missiles to take out ammo dumps and to preclude the possibility of reinforcements. Once you figure out where the enemy is trying to breach, you move reinforcements to that area. I think often about Hitler’s failure to achieve air superiority over the English Channel, when Churchill said , “Never has so much been owed by so many to so few.”

Though air superiority was never on the table for Ukraine in this counteroffensive. That’s correct. The hope was that the Russian forces were fragile, and I don’t think it was an invalid hope. I think it was worth the try.

Because of the disorganization and shambolic nature of their fighting early in the war? Absolutely, but also because of the political fragility of Putin, the internal dissent he’s facing, the loss of so many of the good Russian forces, the evident morale problems we’ve seen among the Russian forces, and poor training among the conscript forces who are defending. But the truth is that defense isn’t just the stronger form of war, it’s the easier form of war. So far, the Russian forces haven’t broken. That’s not to say they won’t, but it’s also the key to this war.

Without western support, Ukraine loses. You can criticize western policy and say we’ve given them just enough not to lose at every phase of the war. I don’t think it’s an unfair criticism, but that certainly hasn’t been why we’ve been relatively stingy with our support, or at least tardy with our support. We are fighting a proxy war. The brave Ukrainians are doing the fighting and the dying, and the United States and our allies are providing the weapons with which they’re conducting that war against a nuclear-armed power.

You can see why Zelenskyy might be frustrated , since the timeline seems to be that he requests something from the U.S., is rejected, and then three months later he gets it. Given this pivotal point in the war, why wouldn’t Biden be a bit more generous right now? Predictions are difficult, especially about the future. President Biden has been feeling Putin out. Putin keeps drawing red lines, and we keep pretty deliberately crossing them and he redraws another red line further back. I have no idea what sort of ears we have listening to Putin and his deliberations, but it appears that we have ears pretty close to Putin, or did. Early in the war, we knew that he was going to attack and broadcast it to the world. Without knowing what’s being said in the Kremlin, I am not willing to fault the Biden administration for being careful as they essentially play chicken with a nuclear-armed power that can destroy the United States in the blink of an eye.

Well, when you put it that way … But that’s the game, right? Biden’s primary responsibility is the safety of the American people, and in my eyes at least, he has balanced his desire to defend Ukraine, preserve the rules-based international order, and stick more than a finger in Putin’s eye. He has achieved all of those objectives while not creating conditions that lead to global thermonuclear war against an opponent who is not necessarily stable.

Where you stand depends on where you sit. Zelenskyy would prefer us to take more risks. He says, “Putin’s not going to go nuclear.” Okay, how do you know that?

Yes, it certainly calls for a good dose of caution. I don’t fault the Biden administration for that. Also, there is no single magic weapon. F-16s are terrific airplanes, but they are effective in a coordinated network of air-defense systems and artillery systems designed for suppression of enemy air defense and airborne-warning and control systems and in-the-air traffic controllers. So giving the Ukrainians F-16s, which is going to happen, isn’t the magic bullet either, because the Russians have not been wasting time.

Ukraine is now the most heavily mined country in the world. There are millions of mines along the front line in Ukraine. The most likely outcome of this war, I think, is a frozen conflict on the ground as we wait to see what happens politically. Who is the next president of the United States? The Ukrainians are watching that with, as you can imagine, enormous interest. As long as the next American president and the next American Congress continue to support Ukraine, Ukraine will not fall. The Ukrainians will continue to fight. They will fight conventionally.

If the country falls, they will fight as insurgents and try to turn this into Afghanistan, after which the Soviet Union essentially ceased to exist. I wrote a piece before the invasion, back in February of ’22, in Foreign Policy . I believed that Ukraine would fall, and I argued that Putin was going to be the dog who caught the truck — that the grinding insurgency that he would be confronted with would lead to the collapse of his regime as it had led to the collapse of the Soviet Union.

I was wrong on the first part. I’m comforted that I had really good company in being wrong. Everybody thought that the Russian advantage was going to prove decisive, including General Milley, who has access to a lot better information than I do. But Ukrainians are absolutely determined to fight for the survival of their country. I just got back from ten days in Poland — I attended the NATO conference on the subject with a bunch of Ukrainian professors, military analysts, people like me. Their determination was absolute. One of the faculty members stood up — her son had been killed the week before. Another of the faculty members talked about his grandma being gunned down by a helicopter. The Russians are literally flying attack helicopters and taking out little babushkas.

Whatever happens on the ground here in the short-term, Ukrainians are going to hate the Russians with a blinding passion for generations to come. This war has been a catastrophe for Russia, and for Putin personally.

One of the few optimistic pieces I’ve read about Ukraine’s position recently was about cluster munitions , and how they were helping break some of these heavily mined lines. Google it for me — I can’t remember who it was, but somebody said, “There’s an awful lot of ruin in the nation.” I think it was a Brit.

It was Adam Smith . Adam Smith said, “There’s a lot of ruin in the nation.” So to paraphrase, there’s an awful lot of ruin in a prepared defense. The cluster munitions are killing an awful lot of Russian soldiers. Certainly the Ukrainians are glad to have them, but by themselves, they are not going to win this war. F-16s are terrific airplanes, by themselves they’re not going to win this war. Additional Leopard tanks are terrific weapons. By themselves, they’re not going to win this war. Have you read Steve Biddle’s piece in Foreign Affairs ?

No. He’s the smartest guy on the planet. He talks through why new weapons don’t make that big of a difference, why it’s hard to create breakthroughs in modern war. The most likely outcome is that this war turns into a frozen conflict, not far from the present lines, until either the West stops supporting Ukraine or the Russians decide to stop prosecuting the war. Probably with the demise of Vladimir Putin.

That seems far off. We came close. Prigozhin quit!

Maybe he was our source all along. That he’s still alive astounds me.

None of it really adds up. None of it adds up, but it certainly inspired the Ukrainians to fight on, right? It’s a huge, huge crack at the waterline in the bad ship Putin. So, that’s what they’re fighting for. They do need to demonstrate to the United States and the West that they’re worth continuing to support, and they are earning that with their blood.

We thought the Russians might be more fragile than they are. That hasn’t turned out to be the case. That doesn’t mean they’re not going to break tomorrow. If a Russian unit cracks at the right place and the Ukrainians happen to have a couple of tank battalions right there? Could they in fact cut the land bridge to Crimea? They could. Is it worth trying? Absolutely. Is it likely? It’s not. But it’s nonzero.

People like Michael Kofman have said that these counteroffensives tend to take many months, and we’re still relatively near the beginning of this one. Was it Hemingway who said, “When you go broke, you grow broke gradually and then all at once.” The counteroffensive succeeds slowly and then all at once.

Is there a particular point where you’d say, “Okay, there’s been no breakthrough. There probably won’t be one”? The fighting conditions go to hell in October. Mud is the enemy, speaking as an old tank driver. If we haven’t had the breakthrough by November, we’re not going to have the breakthrough.

Perhaps it’s more likely that those months would see more political talks, since there’s less possibility for a military advance. Correct. What does political negotiation look like? Is Ukraine willing to settle for getting the Donbas back? The Russians aren’t willing to give up Crimea. The most favorable Russian regime from the West’s perspective wouldn’t give it up. If Navalny is the Russian president, I don’t think he’s willing to do that.

The best outcome I can see for Ukraine is giving up Crimea and an American tank division stationed in Donetsk. That’s a win for Zelenskyy. That’s a win-win for Ukraine. Are the Americans going to be willing to do it? I’m not sure. Again, I’m not sure they should. I don’t want Americans and Russians shooting at each other directly.

Understandably. But Poles? They’re probably ready. The Poles hate the Russians with a blinding passion, and Poland is buying a whole bunch of tanks.

I didn’t quite realize how much Russia’s neighbors hated it until the war. Yeah. It’s one thing not liking your in-laws, it’s another thing when they move in with you.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

- just asking questions

- war in ukraine

- foreign interests

- foreign policy

Most Viewed Stories

- The Package King of Miami

- King Charles Snubs Prince Harry Twice in One Day

- Kari Lake’s Worst Enemy Is a Republican

- This Isn’t the Same Stormy Daniels

- Why President Biden Is Correct to Denounce Campus Antisemitism

Editor’s Picks

Most Popular

- The Package King of Miami By Ezra Marcus

- King Charles Snubs Prince Harry Twice in One Day By Margaret Hartmann

- This Isn’t the Same Stormy Daniels By Olivia Nuzzi and Andrew Rice

- Kari Lake’s Worst Enemy Is a Republican By Casey Quackenbush

- Why President Biden Is Correct to Denounce Campus Antisemitism By Jonathan Chait

What is your email?

This email will be used to sign into all New York sites. By submitting your email, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy and to receive email correspondence from us.

Sign In To Continue Reading

Create your free account.

Password must be at least 8 characters and contain:

- Lower case letters (a-z)

- Upper case letters (A-Z)

- Numbers (0-9)

- Special Characters (!@#$%^&*)

As part of your account, you’ll receive occasional updates and offers from New York , which you can opt out of anytime.

How will the war in Ukraine end? The potential paths forward in Vladimir Putin's ill-conceived invasion

One year after full-scale war returned to Europe for the first time since World War II, the invasion of Ukraine grinds on with no end in sight.

Under the cover of darkness on February 24, 2022, Vladimir Putin acted on a long-held ambition, rolling his tanks across the border and disrupting the lives of 44 million people.

Ukrainians woke up to the sound of panicked texts and calls, and air raid sirens blaring over the capital, the first signs their fragile peace with Russia was broken.

Ordinary citizens with normal, everyday lives were suddenly making heartbreaking decisions over whether to stay and fight or undertake the treacherous journey to a border crossing.

In the space of a fortnight, Natalie Taranec went from teaching at a school in Kyiv to making a desperate dash to the sanctuary city of Lviv and fleeing to another country.

"Leaving Ukraine [is] done with a heavy heart," she said as she packed her bags and prepared for a long drive to the border with her husband.

Among the great uncertainties they faced as they made their decision to leave was about how the invasion would unfold and ultimately end.

One year on, the same question still looms large for many.

Ask any analyst or observer how they think the war in Ukraine will play out, and they'll tell you their guess is only as good as the next offensive.

Less than 12 months ago, few could have imagined the invasion continuing until today, much less predicted its conclusion.

With so much of Ukraine's fate still uncertain, analysts say all outcomes remain possible.

A highly motivated Ukraine may continue to defy the odds, recapturing the land it lost after February 24.

Russia could make a push for more land or the flow of weapons to Kyiv could be halted, bringing forward a stalemate.

Or the war could drag on for years and years at a low ebb. Or it could all end in a small room with both sides laying out their terms for peace.

While the West believes it will be up to Ukraine to decide its future, there is no denying the outcome of the war will have far-reaching consequences for Europe and the rest of the world.

Everyone has a stake in the endgame.

The state of the war

In a two-hour address on Tuesday night, Vladimir Putin gave no indication the war would end any time soon , promising to continue Russia's offensive against its neighbour "step by step".

"I want to repeat. [The West] started the war. And we used force, and are using force, to stop it," he said.

Russian and Ukrainian forces have essentially been locked in a slow, grinding fight since November, particularly around the gateway to the north and central parts of Luhansk, as the war shifted into positional warfare.

While Ukrainian forces still have momentum, Russia currently controls about 18 per cent of Ukraine , including much of Donetsk and Luhansk in the east, as well as Crimea, which it illegally annexed in 2014.

It has also spent the past two months systematically targeting Ukrainian infrastructure, devastating the country's power grid and putting its healthcare services at risk.

By the end of last year, the United Nations had recorded around 18,000 civilian casualties in Ukraine and 50 per cent of its energy infrastructure as destroyed or damaged.

Russia has also suffered immense losses on the battlefield, with US officials estimating a toll of almost 200,000 .

Ukraine's resistance and willingness to fight remains strong, but — if there is a Russian offensive on the horizon as some are predicting — their fortitude will once again be put to the test.

For now, Volodymyr Zelenskyy maintains he will continue to fight to the bitter end.

Mr Putin has suggested the same, claiming he is ready to resume nuclear weapons testing after suspending participation in New Start, the last remaining nuclear arms control treaty between Russia and America.

So, what will unfold next in the war and are there any signs it is reaching its conclusion?

These are some potential scenarios.

Ukraine recaptures its territory

Throughout the war, Western governments have continued to supply aid and weapons to Ukraine and, if that continues, Kyiv's forces could translate that into more battlefield success.

"It's certainly what the Ukrainians are betting on," International Crisis Group's director of the Europe and Central Asia program, Olya Oliker, said.

Ukraine is in a strong position, but a number of things have to line up perfectly for its soldiers to be able to recover all the territory they have lost by the end of this year.

The commander-in-chief of Ukraine's armed forces said in December that his country needed 300 tanks, 600-700 armoured fighting vehicles and 500 howitzers to push the Russians back from their fortified positions.

Analysts say its forces also require more troops and would need to withstand an expected Russian onslaught in spring, between March and May.

If Ukraine manages to clear some of those hurdles, its forces could be in a position by July to retake large portions of land, according to the Royal United Services Institute's former director, Professor Michael Clarke.

While a happy outcome for Ukraine, victory would be contingent on the flow of equipment and aid from the West continuing, which rests on two key factors beyond Kyiv's control: capacity and political will.

After years spent scaling-back artillery, ammunition and tank investments, Europe has cleared out old warehouses to supply Ukraine with the weapons it wants and needs to fight Russia.

Both sides are burning through arsenal at breakneck speed, setting off a mad scramble for remaining Soviet-era equipment such as S-300 air defence missiles, T-72 tanks and artillery shells.

"The current rate of Ukraine's ammunition expenditure is many times higher than our current rate of production. This puts our defence industries under strain," NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg warned this month .

Smaller NATO countries have reportedly exhausted their supplies, leaving a shrinking pool of nations to step up and fill the gap.

Germany and France have announced more support through air missile systems and AMX-10 RC light armoured vehicles, while the US tipped in another $US3.75 billion in new military assistance last month.

US President Joe Biden's recent unannounced trip to Ukraine was also intended to rally NATO support for Ukraine, after insisting there would be no backing down from what he's portrayed as a global struggle between democracy and autocracy.

It comes amid a deepening global divide on the conflict and concern that public support and political will may wane the longer the war drags on.

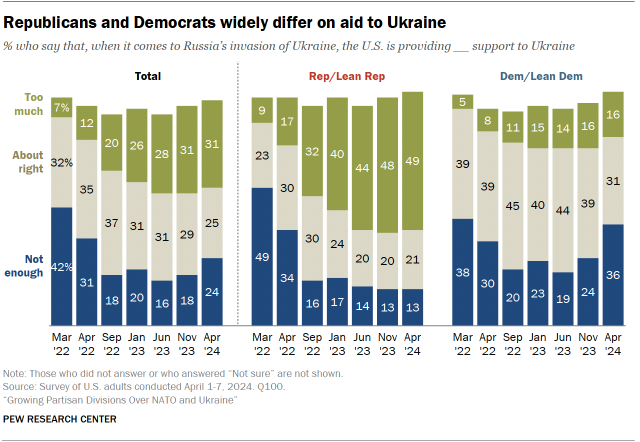

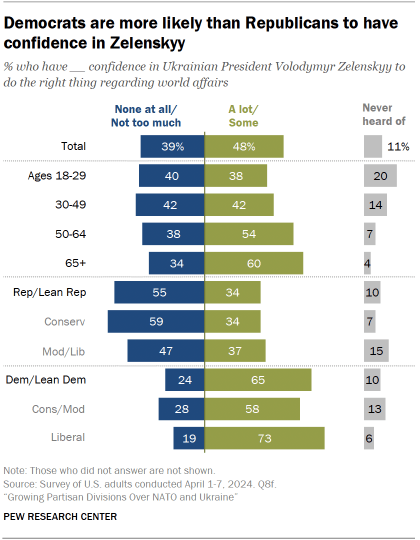

While Americans back providing aid for Ukraine, a recent Pew Research Poll found nearly a quarter believe the country is providing too much support to Ukraine.

And some prominent Republicans — who took over the House from the Democrats in January — have called for an end to US military and other assistance to Ukraine.

"The Ukrainians, I think, have confounded most expectations — [but], I think, this is all contingent on Western support continuing," King's College London professor of conflict and security Tracey German said.

Without ongoing funding and supplies, analysts warn the Ukrainians could falter, turning the war in Russia's favour.

Moscow snatches victory

All signs are pointing to a renewed push from Russian forces, likely involving thousands of soldiers in battalion and brigade-sized attacks , as Moscow continues to hammer Ukraine's energy network.

Mr Putin has already annexed the regions of Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia through so-called referendums after pulling back troops to regroup in eastern Ukraine.

Over the winter, Russia's army had the opportunity to stabilise its front lines and develop new ones, thanks to an injection of fresh recruits from its partial mobilisation in September.

Ukrainian officials believe an emboldened Russia is preparing for another offensive as early as today, having begun the preliminary phase earlier this month .

The Russian side hasn't escalated as much as it can, analysts say, and another offensive aligns with Mr Putin's strategy to double down when backed into a corner.

"[Putin] can't stop, he can't go back," the Centre for Strategic and International Studies' senior advisor and retired Marine colonel Mark Cancian said.

Russian nationalist voices have already expressed skepticism in Russia's ability to launch a successful offensive, but Ukraine's defence minister, Oleksii Reznikov, says Moscow could "try something" to mark the anniversary of its initial invasion.

A possible escalation could involve Russian forces turning the tables on the battlefield and making a push for the south of Ukraine, Professor Clarke said.

The eastern city of Bakhmut, the small town of Vuhledar, Kharkiv and Zaporizhzhia — the gateway to the south — could all be in their sights, the BBC has reported .

"If the Russian spring offensive was successful … they could possibly take all of the area west and [to] the east of the Dnieper River, and then make a puppet state out of what's left of Ukraine," Professor Clarke added.

Or Mr Putin could resort to more-drastic measures, including the use of nuclear weapons, Dr Oliker warns. Nothing is off the table.

It is still unclear what victory would look like for Mr Putin, who has continued to push the false narrative that the West is to blame for the war and framed the invasion as a global conflict.

Analysts say conquering pieces of Ukraine wouldn't necessarily mean an end to the fighting.

"[Russia is] facing three or four generations, 60 or 80 years, of guerilla war, because they're up against a population of 44 million people who are now completely and utterly Ukrainian men," Professor Clarke said.

A stalemate and an armistice

One other possibility is that both sides become exhausted after an inch-by-inch fight, and decide to come to an agreement.

Chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark Milley has previously suggested there was no military solution to the Russia-Ukraine conflict and diplomacy was needed to end the war.

As painful as it is to make compromises in a negotiated settlement, Mr Cancian says Kyiv and Moscow may one day decide peace is the only way forward.

The West — the US, NATO and/or a handful of European countries — could play a hand in hastening that decision, perhaps by offering Ukraine an ultimatum.

However, the terms for how the fighting could end are murky. The current outlook for a negotiated deal would likely involve Ukraine ceding some territory to Russia, analysts say.

Mr Zelenskyy has so far ruled this out as a possibility, proposing a 10-point "formula for peace ," which includes demands for a full withdrawal from Ukraine's territory.

"From a Ukrainian perspective … after the losses that they have endured, particularly over the last year, the question will be … 'Why would they want to seek to negotiate over what is their recognised territory?'" Ms German said.

Neither side has been wiling to come to the negotiation table since the beginning of the war, dashing any hopes for an end to the fighting any time soon.

However, if the war were to drag on this year and into next year, the reasoning could change.

Ukraine could be in a strong position to negotiate once it gets back all of its territory, "including most of what it lost in the Donbas in 2014, with special arrangements made for plebiscites," Professor Clarke said.

Although he added that discussions around Crimea would likely have to be settled separately, possibly going to an international tribunal for discussion and a process of continuing negotiation.

Both sides could engage in a "step-by-step approach to a temporary peace", unfolding in a similar way to previous conflicts, including Cyprus after 1974 and Korea after 1954, Professor Clarke added.

Any progress towards talks would likely start with a ceasefire or a similar type of temporary arrangement that would enable both sides to suspend fighting, the analysts suggest.

A ceasefire would give the Ukrainians a reprieve without backing Mr Putin into a corner, preventing a possible escalation in which he resorts to extreme measures such as attacks on Western energy infrastructure or the use of nuclear weapons.

Sanctions would remain and borders would still be in dispute until a final agreement is reached, which could take years and multiple rounds of ceasefires.

In the meantime, the costs of the war would continue to weigh heavily on Russia, possibly weakening Mr Putin's internal support.

Putin is ousted and the Russian state collapses

As the war drags on, there is growing debate over whether Mr Putin will be around long enough to oversee its end.

The Russian leader's future may depend on the country's powerful security forces, such as those led by Yevgeny Prigozhin or Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov.

Mr Prigozhin's guns for hire have played a critical role in keeping the war going against a backdrop of morale problems, strategic blunders and lack of adequate training.

However, the man dubbed "Putin's chef" has also been a vocal opponent of the Kremlin's inner circle in recent months in a sign that power may be shifting among Russia's political class.

"The elites and potential successors are watching [Putin's] every military move, but they can already see that he has no place in their post-war vision of the future," Russian journalist Andrey Pertsev wrote in his analysis for the Carnegie Endowment .

"His sole remaining function in their perception of the new era of peace will be to nominate a successor and leave the stage."

Professor Clarke said the downfall of Mr Putin was only a matter of time and would likely be brought about from within the military and Russia's security service, with the support of oligarchs fed up with the Kremlin.

Some observers say the likelihood of negotiations between Russia and Ukraine would be more favourable under a different leader.

While the invasion of Ukraine was started and waged by Mr Putin, Alexei Navalny says the real war party is the entire elite and the system of power itself, which is an "endlessly self-reproducing Russian authoritarianism of the imperial kind".

Mr Putin's exit would not end the war in Ukraine because the Russian leader would likely be replaced by another pro-war nationalist, Professor Clarke said.

"So, the war will go on with somebody else," he said.

Forcing Mr Putin out of the Kremlin also carries enormous risks for whoever takes over, by hastening the Russian state's ruin.

If there was no clear successor, Mr Putin's departure could spur on a brutal power struggle among pro-war, right-wing nationalists, authoritarian conservatives and a murky anti-war movement .

This, in turn, would likely weaken the regime and distract Russia from what remains of its war effort.

The war with no end

One final scenario that many have predicted throughout the war is a grinding conflict between Ukraine and Russia lasting many years.

The "special military operation" in Ukraine has already beaten most analysts expectations and, with more offensives planned for this year, there appears to be no end in sight.

The longer the war drags on, there is an increased chance it may slow to "more of a nasty simmer", like the one prior to the full-scale invasion in February, Ms Oliker says.

"It's actually much more sustainable for both countries," she said.

"If it's a smaller front-line, and less fighting, they'd both be building up and looking for a way to break through. But, at least for a while, they'd have a way to rebuild.

"And you could even imagine some kind of, if not a ceasefire, but something that is at least a massive dialling down. But that will be temporary."

A similar situation emerged after the fighting in Ukraine in 2014, with the unresolved conflict featuring a form of continued Russian occupation for many years.

However, there is a risk if this were to happen that Russia would launch another invasion in future, once it had time to replenish its stocks.

What the endgame means for the world

The Ukraine war has had tremendous ripple effects throughout the world's economy by driving up gas prices and inflation rates, impeding the flow of goods, exacerbating world hunger and stretching the entire humanitarian system .

European security was also fundamentally changed by Russia's invasion on February 24 and many states outside of Russia and Ukraine have a stake in its outcome, analysts said.

At the core of why governments are defending Ukraine is the conviction that an emboldened Russia is dangerous for the rest of Europe and, possibly, the world.

"The price we pay is in money, while the price the Ukrainians pay is in blood. If authoritarian regimes see that force is rewarded, we will all pay a much higher price," NATO General Secretary Jens Stoltenberg said at the end of last year.

"And the world will become a more dangerous world for all of us."

If the West remains united with Ukraine, it could make the costs of the war so insurmountable for Russia that it breaks the level of commitment of its political elite.

Mr Putin, on the other hand, is banking on support weakening over time, giving him an opportunity to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat.

Ultimately, there is hope there will one day be an end to the bloodshed.

Although it is tempered by a grim knowledge that one wrong move could escalate the conflict into a situation once considered unthinkable.

A tit-for-tat nuclear altercation is the sort of grim scenario you could imagine not even Mr Putin would desire.

However, with the stakes this high, it's impossible to rule out.

- X (formerly Twitter)

Related Stories

Billions in weapons pledged for ukraine but uncertainty hangs over german tanks.

Russia hasn't been destroyed by Western sanctions. It still has something the rest of the world needs

- Community and Society

- Russian Federation

- Unrest, Conflict and War

- World Politics

Ukraine-Russia war: Expert predictions on where conflict will go next

We've been talking to experts on what we can expect in the third year of Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Kyiv is on the back foot in the fighting - but will anything change that?

Saturday 24 February 2024 22:29, UK

As the war reaches its second anniversary, it's still unclear how it will eventually come to an end.

So, what are we likely to see over the next 12 months? We've been speaking to experts to get their predictions.

'Russia will target these areas next'

Security and defence analyst Professor Michael Clarke says...

Ukraine may well lose more of the territory it has been defending during the rest of this year, but it will be working hard to build up its strength for 2025 and to convince the Western powers that it can prevail against Russia's invasion eventually.

Ukraine war latest: Navalny's body released after mother refuses ultimatum

On the ground, Russia will try to take Kramatorsk and Slovyansk, which would effectively give it the whole of the Donbas region.

At sea, the Ukrainians will try to make the most of the pressure they can put on Crimea through their increasing success in the western part of the Black Sea.

In the air, Russia is making the most of its natural numerical advantage, but Kyiv will be hoping it can turn the air war to hold Russian aircraft further away from its frontline areas.

But most important of all will be the competition for war production between the two sides.

Russia can certainly out-produce Ukraine on its own.

Ukraine can manufacture many good and innovative war stocks but it can only match Russian production levels with the full backing of the Western powers.

This will be the most important - and the most uncertain - front in this war for the coming year.

'Ukraine likely to lose rest of Donbas'

Security and conflict expert Dr Huseyn Aliyev says...

Kyiv will suffer "more serious territorial losses" over the next 12 months, he says.

Reflecting on the recent fall of Avdiivka, he explained a lack of tactical reserves and ammunition - problems the Ukrainians faced during the "botched" defence of Bakhmut in 2023 - were continuing to cause issues.

"As things stand, Ukraine is highly dependent on foreign supplies of ammunition and weapons as two years into the conflict domestic mass production of ammunition is still lagging behind, even when it comes to basic munitions, such as landmines or mortar rounds," he said.

In comparison, Russia has become fast and efficient at "institutional adaptation and learning", Dr Aliyev added.

"All procrastinations on Ukraine's part are likely to lead to more serious territorial losses," he said, warning a lack of domestically made artillery shells and drones could have dire consequences.

"Unless Ukraine engages in construction of defence fortified positions and ramps up domestic production of ammunition, as well as improves mobilization and recruitment, it is likely to lose the rest of Donbas region this year as well as some territories in the south," he said.

'Defeat of Kyiv government could look feasible by end of year'

International affairs editor Dominic Waghorn says...

Both sides in this war are now engaged in what America calls a "hold and build" strategy.

Unable to achieve a breakthrough, Russia and Ukraine are hoping to hold the line while they strengthen their forces.

This is expected to last all year, unless the West chooses to give Ukraine a decisive qualitative edge something it has been too timid and cautious to do so far throughout this conflict.

Without far more substantial support for Ukraine by the end of this period of consolidation, Russia is likely to have the upper hand.

NATO countries have far more economic and military power taken together but they have chosen individually not to share enough of that to give Ukraine the wherewithal to expel the invaders.

Ukraine has been given enough to continue the war, not to win it. There are now doubts over whether it will be sent enough even to stand its ground.

Russia's leader Vladimir Putin knows his survival depends on not losing the war so he is predictably taking all steps to avoid that eventuality.

He is militarising the economy and taking precautions to avoid the inevitable fallout from soaring casualty figures.

He has barred one anti-war rival from running in the upcoming presidential elections and it seems now killed the most prominent critic of his invasion of Ukraine, Alexei Navalny.

Russia has run rings around Western sanctions.

Ed Conway's revealing research is the latest case in point.

And he has enlisted the support of North Korea and it seems more vicariously China in securing supplies of ammunition and weapons that far outweigh the munitions being sent by all of Ukraine's Western backers put together.

There is also still doubt over the strength of military and financial support America is prepared to send Ukraine.

Mr Putin's formidable misinformation machine has sown doubt in the minds of many in the West about the rights and wrongs of the war and the chances of victory.

He has found useful conduits for his falsehoods and half truths, wittingly or not, in the likes of American propagandist Tucker Carlson.

Ukraine has scored some successes at sea sinking a number of Russian warships, but is yielding territory in the ground war, if only incrementally.

But the direction of travel against Ukraine is likely to continue.

If the West chooses not to step up its support to counter the might of Russia's war economy and the support of its allies, a tipping point is likely to be reached towards the end of the year when the defeat of the Kyiv government might start looking feasible.

The West may then learn how sincere Vladimir Putin is when he insists he will not attack NATO countries next, with all that could entail for global security.

'Russian casualties will get increasingly worse'

Former senior military intelligence and security officer Philip Ingram says...

Casualties will remain huge for both sides, but they will get "increasingly worse" for Russia as the West bolsters Ukraine's defences.

"Russia is relying on North Korea and Iran, that does not bode well; the Western defence industrial base, its ammunition manufacturers are finally waking up," he said.

Meanwhile, he said Ukraine has been delivering a "masterclass in strategic manoeuvre" with Special Operations Executive (SOE) operations across occupied territories and into Russia.

This has included assassinations, railway derailments, factories and oil refineries blowing up, as well as military headquarters, airfields and logistic dumps targeted by long-range weapons and the Russian Black Sea Fleet rendered impotent, Mr Ingram explained.

"These combined with resurgent Western supplies will allow Ukraine to regain a multidimensional initiative", he said.

But will it bring a quick end to the war? Mr Ingram said it is "highly unlikely, unless there is a major change in Moscow".

"We will be talking about the Russia-Ukraine war in another 730 days, I believe," he added.

"However, in another 730 days Russia will be significantly weakened, it simply can't afford much more, whereas in the West, affordability is merely a political decision as the price for Ukraine losing is significantly greater.

"It is that that will ensure continued Western support no matter what election outcomes unfold."

'Third year of war could prove more difficult for Zelenskyy'

Military analyst Sean Bell says...

The key to Ukraine's fortunes lie with Vladimir Putin, and 2024 could prove to be a very difficult year.

"Although Western political support for President Zelenskyy appears relatively robust, translating that rhetoric into a steady supply of battle-winning weapons is proving increasingly difficult," he adds.

"Western war chests are depleted, and without weapons and ammunition, Ukraine's prospects are bleak."

However, he points out Russia will face the same challenge and will try to cultivate links with North Korea and Iran to augment its own defence industrial base, funded by growing oil revenues.

"The presidential elections could prove crucial," he says.

"A change of administration in the USA could herald a reduction in financial and military support for Ukraine this coming year.

"Even with massive support in 2023, Ukraine was unable to break through Russian lines. Any reduction of support could be critical.

"And, with Russia's presidential elections behind him, Putin could feel emboldened to 'double-down' on his special military operation in Ukraine.

"Year two of this conflict started with a sense of optimism for the coming Ukrainian spring offensive.

"However, without a determined, coherent and credible western strategy to provide Ukraine with the weapons and ammunition it needs to prevail, this could prove a much more difficult year for President Zelenskyy."

'West cannot afford to miscalculate in 2024'

Researcher Jaroslava Barbieri says...

2024 will be the year the West plays a vital role.

While she predicts Russia will keep hold of material and manpower advantages, she believes the EU and NATO will "seriously commit" to improving Ukraine's defence capabilities.

In 2022 the West underestimated Ukraine's ability to fight. In 2023 the West underestimated Russia's ability to recover from its military setbacks and sustain a long-term war," she said.

"The policy of drip-feeding weapons into Ukraine reflected Western governments' illusion that supporting Ukraine's victory could mean something other than inflicting a decisive defeat on Russia.

"2024 is the year when the West cannot afford to miscalculate again."

"The future of the war hinges on the West coming to terms with the reality that it's an existential war not only for Ukraine, but the West as a whole."

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

In her view, the best case scenario will see Donald Trump staying out of the White House and Western powers drawing up a coherent plan on how to use Russia's frozen assets to Ukraine's advantage.

In turn, Ukraine will boost mobilisation, hold defensive lines and build up its air defences.

She said Kyiv would then increase drone attacks, especially in Crimea, and acquire long-range precision strike capabilities to hit deep behind enemy lines.

"Together, these factors will allow Ukraine to rebuild its capacity to conduct large-scale offensive operations in 2025," she said.

However, a worst case scenario would see the "return of American isolationism and European political paralysis".

"Facing severe shell shortages, Ukrainian soldiers would be forced to scale back military operations," she explained.

"Ukraine's inability to replenish its battlefield manpower would exacerbate brewing tensions inside Ukrainian society.

"The Kremlin would continue to exploit any sign of Western hesitation to push the narrative that Ukraine cannot win this war and that negotiating a deal on Moscow's terms is the only option.

"In turn, this could possibly lead to a new wave of Ukrainian refugees."

'Key US support well in the balance'

Our US correspondent Mark Stone says...

The war in the Middle East has somewhat overshadowed an almighty and long-running row in Washington about funding for Ukraine.

As Sky News' own eyewitness reporting has revealed, the Ukrainian military is close to running out of weapons and ammunition.

On the ground in eastern Ukraine, Vladimir Putin has the upper hand.

European foreign ministers meeting here in New York aren't even trying to argue otherwise.

Read more: UK and other NATO allies urged to consider conscription Two Britons who nearly died fighting in Ukraine reveal why they returned Alexei Navalny's widow accuses Vladimir Putin of 'fake' faith

In Washington, a small but influential group of Trumpian politicians representing doubting constituents across the country are blocking a bill to send another huge tranche of weapons to Ukraine.

There is absolutely no guarantee that they will allow it to pass.

It's striking that European foreign ministers who are at the UN to mark the anniversary are focusing their messaging on America, not Russia.

With quite blunt language, they are calling for America to step up and continue to support Ukraine.

"It is in the interests of the American people," the foreign ministers of Britain, Germany and Poland said at an event on 5th Avenue this morning.

It's a message that isn't landing in America yet.

The "America first/security begins at home" message, and confusion over the merits of funding a far-away war, run deep across many parts of America.

And remember - the prospects for the Ukraine war could shift even more profoundly should Donald Trump be elected in November.

We are approaching a moment in this long war where fortunes could shift profoundly.

Related Topics

How Ukraine Must Change If It Wants to Win

A beleaguered country needs more than volunteerism and chutzpah to protect its version of democracy.

Listen to this article

Produced by ElevenLabs and News Over Audio (NOA) using AI narration.

This article was updated at 9:45 a.m. ET on January 9, 2024

On December 29 , Russia launched the largest missile attack against Ukraine since the start of the full-scale invasion. On January 2, another attack of the same magnitude hit schools, hospitals, and apartment blocks across Ukraine. Early yesterday morning—the day after Orthodox Christmas—the Russians hurled yet another missile barrage at Ukraine. Together, these attacks sent a message: Russian President Vladimir Putin is not interested in negotiations, cease-fires, or swapping land for peace. Although he cannot overwhelm Ukraine militarily, Putin now believes that he can keep up the pressure, destroy Ukraine’s civilian infrastructure, wait for Ukraine’s allies to grow tired, goad the Ukrainian public into turning against the government, and then win by default.

Often, this new phase of fighting is described as a “war of attrition,” as if the only thing that will determine the outcome is the number of bullets. But although the number of bullets does matter, the war has an important narrative and psychological component too. Alongside the bombings, Kremlin officials are now telegraphing to everyone—to Western politicians and journalists, to Ukraine, to the Russian people—that they can absorb 300,000 casualties and massive equipment losses, that their country’s economy is thriving, that they are willing to devote half of the national budget to defense production indefinitely. At the same time, the Russians and their supporters in the United States and Europe describe Ukraine as corrupt, politically divided, and, above all, certain to lose. In Washington, some Republicans justify their (so far) successful attempt to block American aid to Ukraine by using this language. Viktor Orbán, the Hungarian prime minister who courts investment from Russia and China, does the same when blocking European aid.

From the June 2023 issue: The counteroffensive

Ukrainians know that negotiations with Russia are fruitless, and in any case not on offer. They also know that military loss still means the same thing that it meant when Russia invaded in February 2022: occupation, mass repression, concentration camps, and the end of an independent Ukraine. They also know that the Russians are much weaker than they claim. Their soldiers still stumble into traps; their commanders still seem to be improvising. The Russian public is tired of the war and of the falling living standards it has created . Nevertheless, to beat the Russians militarily and psychologically, to undermine the Russian propaganda repeated by Orbán and the MAGA right, to maintain their alliances and defend their territory until the Russians have had enough, they have to change.

Two years ago, in the weeks that followed the full-scale invasion, ordinary people pitched in to buy night-vision goggles, the managers of chic bistros mobilized to feed troops, men drove their children to the border and then went home to fight in the territorial army. Now the volunteerism, chutzpah, and wild energy that carried the army and the society forward for the past two years have to be transformed into systems, institutions, and rules. Ukraine needs not just the most enthusiastic army, but the best-managed. Ukraine needs not just clever engineers who build innovative sea drones , but the most modern defense industry in Europe, if not the world. Finally, Ukraine’s government needs to eliminate any remaining corruption and mismanagement—and convince its allies that it has done so as well.

I did not invent these recommendations. I heard them in Kyiv, late last month, from Rustem Umerov, Ukraine’s new defense minister.

To outsiders, Umerov might seem an odd choice for this job. Born in 1982 in Uzbekistan because Stalin had sent Umerov’s Crimean Tatar family into exile there in 1944, Umerov returned to Crimea with his parents only in 1991, when Ukraine became independent from Moscow’s control. When he was still very young, Umerov told me, he “understood how to be what is now known as a refugee.”

His memories of resettlement and his membership in Ukraine’s Muslim Tatar minority might have led him to feel excluded or alienated. Instead, he drew for me a clear line from his childhood experience of exile to his present role in defending Ukraine. From the time he was a student, he understood that the Tatars are only safe when Crimea is part of a democratic, tolerant Ukraine—but a democratic, tolerant Ukraine is only guaranteed if Ukraine is part of Europe. He was an advocate of Ukrainian membership in NATO and the European Union when that position wasn’t particularly popular. “We want to be a part of the civilized world,” Umerov now says, “part of the rule-of-law world … What Russia proposes is no rule of law, no development, aggression towards all their neighbors.”

Following the Russian occupation of Crimea in 2014, when many Tatars were expelled from their homes once again, Umerov became an advocate for Crimean political prisoners, directly negotiating for their release. Starting in February 2022, he served again several times as one of Ukraine’s intermediaries with Russia, as well as with Turkey and the Gulf States, both formally and informally.

Along the way, he obtained a reputation for competence. When I asked others about him in Kyiv, they mentioned the languages he speaks (which include Turkish as well as English, Russian and Ukrainian) as well as his wide range of contacts, lack of pretension, and absence of drama. I met him in the same featureless conference room where I had previously met his predecessor, Oleksiy Reznikov, a personable lawyer who forged good relationships with his foreign counterparts but retired amid a series of news stories about Defense Ministry corruption . Reznikov was not personally implicated: Since 2022, in fact, there has been no suggestion of misused foreign aid or of high-level corruption in the Ukrainian army. But there has been overcharging and waste, just like in the U.S. military—the difference being that if the Ukrainian army has a shortage of winter uniforms because someone has written a bad contract, people might die.

Ending both the reality and the impression of sloppiness is now Umerov’s second-most important task. It’s also part of a larger problem, he told me. Ukraine needs everything, all the time: artillery rounds, winter shoes, F-16s. Prioritizing the army’s needs, translating that into concrete purchases and coordinating with both Western companies and Ukraine’s growing defense industry is a complicated managerial problem that needs more than one solution. Umerov mentioned several, including the creation of 10-year contracts that will help both domestic and foreign companies plan long term, and investment conferences designed to encourage Western companies to cooperate directly with Ukraine. When talking about these changes, he makes frequent reference to “OECD rules” and “NATO standards.” He also talks about “systems” and “transparency.” These are not buzzwords. Ukraine’s continued existence depends on making them mean something real.

Read: Can Ukraine clean up its defense industry fast enough?

Umerov’s more important task—Ukraine’s most important task—involves people, not shoes and bullets. Ukraine needs to recruit and train more soldiers, as well as to give veterans a rest from combat. Fear and paranoia about military service are growing; there are reports of people being pressed into the army and of others trying to sneak across borders and swim across rivers in order to dodge mobilization. Umerov understands this, again, both as a narrative problem and a real one. He wants to change the tone of the conversation: “This is not a punishment,” he says of military service. “It’s an honor.” But everyone is afraid of the unknown, he told me, and right now military service involves a lot of unknowns. “People should understand how they will be trained, how they will be fed, how they will be taken care of during the operation. And then how they will exit .” The details are still a matter of debate, but he wants to end the uncertainty, negotiate new rules with the military and with Parliament, create a national military-service database and then give all military-age citizens a clear set of options.

For Ukraine to weather Russia’s narrative war, Umerov also thinks that the Ukrainian political debate needs a “decompression.” The purported rivalry between the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky, and the chief of the army, Valery Zaluzhny, has had a lot of airtime in the Ukrainian media. Umerov is widely thought to be one of the people who bring the two men together. When I asked him about the friction between them, he replied that he just wants these discussions to become less exciting: “It’s also normal, you know, for there to be disagreements between people. I mean, okay, there’s general unity, everybody wants to win the war, but there can be different opinions.” Instead of politicizing disagreements or making a fetish of them, “we should be focused on the objectives, strategic objectives, military objectives.”

None of these tasks is simple, and any of them could trip up larger, richer, and less embattled countries. Russia has a much larger population but has made a mess of mobilization, which it now does by stealth, forcing ethnic minorities and even foreigners with work visas into their army. European democracies have so far failed to rapidly ramp up domestic military production, even in the face of a growing, existential threat from Russia. The U.S., meanwhile, is incapable of any kind of decompression: Americans have hardly any debates that are calm, apolitical, and “focused on the objectives.” All of our conversations about Ukraine, just to take one relevant example, are now fully politicized: A part of the Republican Party is opposing aid to Ukraine simply because that harms Joe Biden.

But then, we don’t face the same stakes. Ukraine’s battle against Russia has always been a civilizational clash, between an open society and a closed one, a rule-of-law society and a dictatorship. Ukrainians are still betting that their version of democracy is not just more attractive than Russian autocracy but more effective. On the way out of Umerov’s office, I met some of his younger colleagues, who were joking about how confusing expressions like “institutional transformation” can sound to many Ukrainians, especially the older employees of the massive apparatus that is the Defense Ministry. But they weren’t suggesting that they won’t try to explain, or that they won’t eventually implement an institutional transformation and win the war. If they believe in Ukraine’s future, so should we.

- Subscribe Digital Print

- Tourism in Japan

- Latest News

- Deep Dive Podcast

Today's print edition

Home Delivery

- Crime & Legal

- Science & Health

- More sports

- CLIMATE CHANGE

- SUSTAINABILITY

- EARTH SCIENCE

- Food & Drink

- Style & Design

- TV & Streaming

- Entertainment news

The best outcome for Ukraine in this conflict

A look at possible endings as putin’s 'shock without awe' turns into a war of attrition..

Three months after Russia’s unprovoked attack on Ukraine, the war is entering a new phase. This change requires all involved — the Kremlin as well as Kyiv and its supporters in the West — to rethink scenarios, goals and strategies.

Phase 1 of the war, starting on Feb. 24, might be called "Shock Without Awe." Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered his army to invade, bomb and destroy Ukraine from all sides and to kill his counterpart in Kyiv, Volodymyr Zelenskyy. By shocking Ukrainians, Putin was expecting to awe them into submission.

Instead, they became a nation of heroes, from Zelenskyy ("I need ammunition, not a ride”) to all the men, women and children who sacrificed and stood together against the Russian onslaught. The symbol of the country’s will to resist became Azovstal, a steel plant in the now-destroyed city of Mariupol that the Ukrainians, for a time, defended against all odds.

This month, that phase ended. Understanding that this war will be neither quick nor easy, Putin commanded his forces to concentrate on taking "only” Ukraine’s east and south. In Mariupol, the last remaining Ukrainians evacuated Azovstal. Russia is massing its firepower for a new and more focused assault. Ukraine, receiving guns and ammo from the West, is preparing to fight back.

Phase 2 therefore looks likely to be less kinetic and more grinding — less like a Blitzkrieg and more like a war of attrition evoking the trenches of World War I. My guess is that each side will gain, lose and retake territory in an interminable clash of wills that only makes the rubble bounce.

What, then, could Phase 3 eventually look like and ultimately the war’s end? A decisive military outcome seems unlikely — and possibly even undesirable.

If the Russians "won” — that is, if they routed the Ukrainian Army — they would dismember or eliminate Ukraine as a country and subjugate much of its population. But the Russians won’t succeed in that way, because Ukraine is getting more and better weapons by the day and will hold out.

If the Ukrainians "won,” they would drive the Russians back at least beyond the frontlines as they stood on Feb. 23. But that would amount to a catastrophic failure that Putin couldn’t hide from his population. He would fear for his political and physical survival, which he would redefine as an existential threat to the Russian state. This is the scenario in which he might "escalate to de-escalate” by launching tactical nuclear strikes until Ukraine surrenders.

This would be the worst of all outcomes, possibly even drawing in the West. But I don’t think it’ll come to that, because the Ukrainians probably can’t expel the Russian forces anyway. For that, Russia can still mobilize too much conventional military might.

In a likelier scenario, therefore, the war drags on and increasingly looks like a stalemate. This, too, would be disastrous, for both sides.

Large parts of Ukraine would be destroyed, while other regions couldn’t start rebuilding. The millions of Ukrainian refugees — mostly women and children — couldn’t return and would settle into new lives in western Europe and elsewhere. Eventually, fathers and husbands at home would seek to join them. Ukraine, even with billions in Western aid, would be permanently stunted.

Russia, meanwhile, would indefinitely remain the international pariah it now is. The rest of Europe will gradually wean itself from its fossil fuels, turning off the Kremlin’s money tap. Components and technologies won’t enter Russia, while talented people will keep leaving it. The country will become an impoverished and totalitarian dystopia.

Sooner or later, therefore, sheer exhaustion will prod both sides to negotiate. As ever, each will try to show up at the talks holding as much territory as possible, which will make the lead-up even more barbarous and bloody. But then there’ll be give and take.

Whatever Kyiv says now, it can’t expect to get back Crimea, Luhansk or Donetsk. Putin annexed the former and recognized the latter two as "People’s Republics,” with the obvious aim of gobbling them. He couldn’t give them up and still claim victory at home. But Kyiv should insist on keeping its coastline on the Black Sea, lest Ukraine become landlocked and indefensible in the long run.

Wherever the final line of confrontation runs, the real question is what the ceasefire, truce or armistice will look like. One possibility is a Korean model. As on that peninsula since 1953, there would be no peace treaty, just mutual despair yielding a cessation of fighting along some sort of demilitarized zone.

But such an outcome would be much less promising for Ukraine than it proved for South Korea. Both are permanently threatened by totalitarian neighbors with nukes. But South Korea, unlike Ukraine, had the explicit protection of the U.S. and gradually became the glittering economic and cultural power it is under that American aegis. Ukraine will just as explicitly lack NATO protection, because the West wants to avoid a Third World War.

Another scenario is the Finnish model. In the Winter War of 1939-40, Finland fought a Soviet invasion to a standstill and kept its independence in return for ceding some territory to the USSR. But this success came at the cost of compromising its sovereignty: It became a neutral buffer state that coordinated its foreign policy with Moscow — a quasi-independence pejoratively called "Finlandization.”

Finland eventually became the success story it is today. It has a strong national identity, loves freedom and is prepared to fight for it. After the Cold War, it entered the European Union. This year, at last, it will almost certainly join NATO. In the long run, the Finnish model is, therefore, more promising for Ukraine than the Korean or any other.

And yet, Ukrainians, like the Finns during the Cold War, would probably have to wait decades for their bliss. That’s not an easy proposition for Zelenskyy or anybody else to sell to a traumatized population yearning for justice.

The devastating reality of Putin’s war is that, for the foreseeable future, it can lead only to outcomes that are messy and tragic. Little or nothing will be resolved. Success, such as it is, will be merely the avoidance of even worse catastrophes.

Andreas Kluth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European politics. A former editor in chief of Handelsblatt Global and a writer for the Economist, he is author of "Hannibal and Me.”

In a time of both misinformation and too much information, quality journalism is more crucial than ever. By subscribing, you can help us get the story right.

Advertisement

Supported by

Ukraine Retreats From Villages on Eastern Front as It Awaits U.S. Aid

Ukraine’s top commander said his outgunned troops were facing a dire situation as Russia tried to push its advantage before the first batch of an American military package arrives.

- Share full article

By Constant Méheut

Reporting from Kyiv, Ukraine

Russian troops have captured or entered around a half-dozen villages on Ukraine’s eastern front over the past week, highlighting the deteriorating situation in the region for outgunned and outnumbered Ukrainian forces as they wait for long-needed American military aid.

“The situation at the front has worsened,” Gen. Oleksandr Syrsky, Ukraine’s top commander, said in a statement on Sunday in which he announced that his troops had retreated from two villages west of Avdiivka, a Ukrainian stronghold in the east that Russia seized earlier this year, and another village further south.

Military experts say Moscow’s recent advances reflect its desire to exploit a window of opportunity to press ahead with attacks before the first batch of a new American military aid package arrives in Ukraine to help relieve its troops.

Congress recently approved $60 billion in military aid for Ukraine , and President Biden signed it last week, vowing to expedite the shipment of arms.

“In an attempt to seize the strategic initiative and break through the front line, the enemy has focused its main efforts on several areas, creating a significant advantage in forces and means,” General Syrsky said on Sunday.

Here’s a look at the current situation.

A slow but steady advance near Avdiivka

General Syrsky said the “most difficult situation” at the moment was around the villages west of Avdiivka, which Russia captured in February after months of fierce battles. He said Russia had deployed up to four brigades in the area with the goal of advancing toward Ukrainian military logistical hubs, such as the eastern city of Pokrovsk.

After Russia captured Avdiivka, Ukrainian forces fell back to a new defensive line about three miles to the west, along a series of small villages, but that line has now been overrun by Russian forces. General Syrsky said on Sunday that his troops had withdrawn from Berdychi and Semenivka, the last two villages in that area that were not yet under full Russian control.

Serhii Kuzan, the chairman of the Ukrainian Security and Cooperation Center, a nongovernmental research group, said the Ukrainian command had to make “a choice between a bad situation and an even worse one” and decided to lose territories rather than soldiers.

Further complicating the situation, Russian forces have managed to break through t he northern part of this defensive line by exploiting a gap in Ukrainian positions and quickly advancing into the village of Ocheretyne. That village sits on a road leading to Pokrovsk, about 18 miles to the west. It is unclear whether Russian forces have gained full control of it.

The offensive on Chasiv Yar

The Institute for the Study of War , a Washington-based think tank, said on Sunday that Russia’s gains in Ocheretyne presented the Russian command with a choice: continue to push west toward Pokrovsk, or push north toward Chasiv Yar, a town that has suffered relentless Russian attacks in recent weeks.

As many as 25,000 Russian troops are involved in an offensive on Chasiv Yar, according to Ukrainian officials. Chasiv Yar, about seven miles west of Bakhmut, lies on strategic high ground.

Its capture would put the town of Kostiantynivka, some 10 miles to the southwest, in Moscow’s direct line of fire. The town is the main supply point for Ukrainian forces along much of the eastern front.

A push northward from Ocheretyne could also allow the Russian forces to attack Kostiantynivka from the south, in a pincer movement.

“Russian forces currently have opportunities to achieve operationally significant gains near Chasiv Yar,” the Institute for the Study of War said in its report on Sunday.

Tough weeks ahead