Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1.3 The Economists’ Tool Kit

Learning objectives.

- Explain how economists test hypotheses, develop economic theories, and use models in their analyses.

- Explain how the all-other-things unchanged (ceteris paribus) problem and the fallacy of false cause affect the testing of economic hypotheses and how economists try to overcome these problems.

- Distinguish between normative and positive statements.

Economics differs from other social sciences because of its emphasis on opportunity cost, the assumption of maximization in terms of one’s own self-interest, and the analysis of choices at the margin. But certainly much of the basic methodology of economics and many of its difficulties are common to every social science—indeed, to every science. This section explores the application of the scientific method to economics.

Researchers often examine relationships between variables. A variable is something whose value can change. By contrast, a constant is something whose value does not change. The speed at which a car is traveling is an example of a variable. The number of minutes in an hour is an example of a constant.

Research is generally conducted within a framework called the scientific method , a systematic set of procedures through which knowledge is created. In the scientific method, hypotheses are suggested and then tested. A hypothesis is an assertion of a relationship between two or more variables that could be proven to be false. A statement is not a hypothesis if no conceivable test could show it to be false. The statement “Plants like sunshine” is not a hypothesis; there is no way to test whether plants like sunshine or not, so it is impossible to prove the statement false. The statement “Increased solar radiation increases the rate of plant growth” is a hypothesis; experiments could be done to show the relationship between solar radiation and plant growth. If solar radiation were shown to be unrelated to plant growth or to retard plant growth, then the hypothesis would be demonstrated to be false.

If a test reveals that a particular hypothesis is false, then the hypothesis is rejected or modified. In the case of the hypothesis about solar radiation and plant growth, we would probably find that more sunlight increases plant growth over some range but that too much can actually retard plant growth. Such results would lead us to modify our hypothesis about the relationship between solar radiation and plant growth.

If the tests of a hypothesis yield results consistent with it, then further tests are conducted. A hypothesis that has not been rejected after widespread testing and that wins general acceptance is commonly called a theory . A theory that has been subjected to even more testing and that has won virtually universal acceptance becomes a law . We will examine two economic laws in the next two chapters.

Even a hypothesis that has achieved the status of a law cannot be proven true. There is always a possibility that someone may find a case that invalidates the hypothesis. That possibility means that nothing in economics, or in any other social science, or in any science, can ever be proven true. We can have great confidence in a particular proposition, but it is always a mistake to assert that it is “proven.”

Models in Economics

All scientific thought involves simplifications of reality. The real world is far too complex for the human mind—or the most powerful computer—to consider. Scientists use models instead. A model is a set of simplifying assumptions about some aspect of the real world. Models are always based on assumed conditions that are simpler than those of the real world, assumptions that are necessarily false. A model of the real world cannot be the real world.

We will encounter our first economic model in Chapter 35 “Appendix A: Graphs in Economics” . For that model, we will assume that an economy can produce only two goods. Then we will explore the model of demand and supply. One of the assumptions we will make there is that all the goods produced by firms in a particular market are identical. Of course, real economies and real markets are not that simple. Reality is never as simple as a model; one point of a model is to simplify the world to improve our understanding of it.

Economists often use graphs to represent economic models. The appendix to this chapter provides a quick, refresher course, if you think you need one, on understanding, building, and using graphs.

Models in economics also help us to generate hypotheses about the real world. In the next section, we will examine some of the problems we encounter in testing those hypotheses.

Testing Hypotheses in Economics

Here is a hypothesis suggested by the model of demand and supply: an increase in the price of gasoline will reduce the quantity of gasoline consumers demand. How might we test such a hypothesis?

Economists try to test hypotheses such as this one by observing actual behavior and using empirical (that is, real-world) data. The average retail price of gasoline in the United States rose from an average of $2.12 per gallon on May 22, 2005 to $2.88 per gallon on May 22, 2006. The number of gallons of gasoline consumed by U.S. motorists rose 0.3% during that period.

The small increase in the quantity of gasoline consumed by motorists as its price rose is inconsistent with the hypothesis that an increased price will lead to an reduction in the quantity demanded. Does that mean that we should dismiss the original hypothesis? On the contrary, we must be cautious in assessing this evidence. Several problems exist in interpreting any set of economic data. One problem is that several things may be changing at once; another is that the initial event may be unrelated to the event that follows. The next two sections examine these problems in detail.

The All-Other-Things-Unchanged Problem

The hypothesis that an increase in the price of gasoline produces a reduction in the quantity demanded by consumers carries with it the assumption that there are no other changes that might also affect consumer demand. A better statement of the hypothesis would be: An increase in the price of gasoline will reduce the quantity consumers demand, ceteris paribus. Ceteris paribus is a Latin phrase that means “all other things unchanged.”

But things changed between May 2005 and May 2006. Economic activity and incomes rose both in the United States and in many other countries, particularly China, and people with higher incomes are likely to buy more gasoline. Employment rose as well, and people with jobs use more gasoline as they drive to work. Population in the United States grew during the period. In short, many things happened during the period, all of which tended to increase the quantity of gasoline people purchased.

Our observation of the gasoline market between May 2005 and May 2006 did not offer a conclusive test of the hypothesis that an increase in the price of gasoline would lead to a reduction in the quantity demanded by consumers. Other things changed and affected gasoline consumption. Such problems are likely to affect any analysis of economic events. We cannot ask the world to stand still while we conduct experiments in economic phenomena. Economists employ a variety of statistical methods to allow them to isolate the impact of single events such as price changes, but they can never be certain that they have accurately isolated the impact of a single event in a world in which virtually everything is changing all the time.

In laboratory sciences such as chemistry and biology, it is relatively easy to conduct experiments in which only selected things change and all other factors are held constant. The economists’ laboratory is the real world; thus, economists do not generally have the luxury of conducting controlled experiments.

The Fallacy of False Cause

Hypotheses in economics typically specify a relationship in which a change in one variable causes another to change. We call the variable that responds to the change the dependent variable ; the variable that induces a change is called the independent variable . Sometimes the fact that two variables move together can suggest the false conclusion that one of the variables has acted as an independent variable that has caused the change we observe in the dependent variable.

Consider the following hypothesis: People wearing shorts cause warm weather. Certainly, we observe that more people wear shorts when the weather is warm. Presumably, though, it is the warm weather that causes people to wear shorts rather than the wearing of shorts that causes warm weather; it would be incorrect to infer from this that people cause warm weather by wearing shorts.

Reaching the incorrect conclusion that one event causes another because the two events tend to occur together is called the fallacy of false cause . The accompanying essay on baldness and heart disease suggests an example of this fallacy.

Because of the danger of the fallacy of false cause, economists use special statistical tests that are designed to determine whether changes in one thing actually do cause changes observed in another. Given the inability to perform controlled experiments, however, these tests do not always offer convincing evidence that persuades all economists that one thing does, in fact, cause changes in another.

In the case of gasoline prices and consumption between May 2005 and May 2006, there is good theoretical reason to believe the price increase should lead to a reduction in the quantity consumers demand. And economists have tested the hypothesis about price and the quantity demanded quite extensively. They have developed elaborate statistical tests aimed at ruling out problems of the fallacy of false cause. While we cannot prove that an increase in price will, ceteris paribus, lead to a reduction in the quantity consumers demand, we can have considerable confidence in the proposition.

Normative and Positive Statements

Two kinds of assertions in economics can be subjected to testing. We have already examined one, the hypothesis. Another testable assertion is a statement of fact, such as “It is raining outside” or “Microsoft is the largest producer of operating systems for personal computers in the world.” Like hypotheses, such assertions can be demonstrated to be false. Unlike hypotheses, they can also be shown to be correct. A statement of fact or a hypothesis is a positive statement .

Although people often disagree about positive statements, such disagreements can ultimately be resolved through investigation. There is another category of assertions, however, for which investigation can never resolve differences. A normative statement is one that makes a value judgment. Such a judgment is the opinion of the speaker; no one can “prove” that the statement is or is not correct. Here are some examples of normative statements in economics: “We ought to do more to help the poor.” “People in the United States should save more.” “Corporate profits are too high.” The statements are based on the values of the person who makes them. They cannot be proven false.

Because people have different values, normative statements often provoke disagreement. An economist whose values lead him or her to conclude that we should provide more help for the poor will disagree with one whose values lead to a conclusion that we should not. Because no test exists for these values, these two economists will continue to disagree, unless one persuades the other to adopt a different set of values. Many of the disagreements among economists are based on such differences in values and therefore are unlikely to be resolved.

Key Takeaways

- Economists try to employ the scientific method in their research.

- Scientists cannot prove a hypothesis to be true; they can only fail to prove it false.

- Economists, like other social scientists and scientists, use models to assist them in their analyses.

- Two problems inherent in tests of hypotheses in economics are the all-other-things-unchanged problem and the fallacy of false cause.

- Positive statements are factual and can be tested. Normative statements are value judgments that cannot be tested. Many of the disagreements among economists stem from differences in values.

Look again at the data in Table 1.1 “LSAT Scores and Undergraduate Majors” . Now consider the hypothesis: “Majoring in economics will result in a higher LSAT score.” Are the data given consistent with this hypothesis? Do the data prove that this hypothesis is correct? What fallacy might be involved in accepting the hypothesis?

Case in Point: Does Baldness Cause Heart Disease?

Mark Hunter – bald – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

A website called embarrassingproblems.com received the following email:

What did Dr. Margaret answer? Most importantly, she did not recommend that the questioner take drugs to treat his baldness, because doctors do not think that the baldness causes the heart disease. A more likely explanation for the association between baldness and heart disease is that both conditions are affected by an underlying factor. While noting that more research needs to be done, one hypothesis that Dr. Margaret offers is that higher testosterone levels might be triggering both the hair loss and the heart disease. The good news for people with early balding (which is really where the association with increased risk of heart disease has been observed) is that they have a signal that might lead them to be checked early on for heart disease.

Source: http://www.embarrassingproblems.com/problems/problempage230701.htm .

Answer to Try It! Problem

The data are consistent with the hypothesis, but it is never possible to prove that a hypothesis is correct. Accepting the hypothesis could involve the fallacy of false cause; students who major in economics may already have the analytical skills needed to do well on the exam.

Principles of Economics Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

1.3 How Economists Use Theories and Models to Understand Economic Issues

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Interpret a circular flow diagram

- Explain the importance of economic theories and models

- Describe goods and services markets and labor markets

John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), one of the greatest economists of the twentieth century, pointed out that economics is not just a subject area but also a way of thinking. Keynes ( Figure 1.6 ) famously wrote in the introduction to a fellow economist’s book: “[Economics] is a method rather than a doctrine, an apparatus of the mind, a technique of thinking, which helps its possessor to draw correct conclusions.” In other words, economics teaches you how to think, not what to think.

Watch this video about John Maynard Keynes and his influence on economics.

Economists see the world through a different lens than anthropologists, biologists, classicists, or practitioners of any other discipline. They analyze issues and problems using economic theories that are based on particular assumptions about human behavior. These assumptions tend to be different than the assumptions an anthropologist or psychologist might use. A theory is a simplified representation of how two or more variables interact with each other. The purpose of a theory is to take a complex, real-world issue and simplify it down to its essentials. If done well, this enables the analyst to understand the issue and any problems around it. A good theory is simple enough to understand, while complex enough to capture the key features of the object or situation you are studying.

Sometimes economists use the term model instead of theory. Strictly speaking, a theory is a more abstract representation, while a model is a more applied or empirical representation. We use models to test theories, but for this course we will use the terms interchangeably.

For example, an architect who is planning a major office building will often build a physical model that sits on a tabletop to show how the entire city block will look after the new building is constructed. Companies often build models of their new products, which are more rough and unfinished than the final product, but can still demonstrate how the new product will work.

A good model to start with in economics is the circular flow diagram ( Figure 1.7 ). It pictures the economy as consisting of two groups—households and firms—that interact in two markets: the goods and services market in which firms sell and households buy and the labor market in which households sell labor to business firms or other employees.

Firms produce and sell goods and services to households in the market for goods and services (or product market). Arrow “A” indicates this. Households pay for goods and services, which becomes the revenues to firms. Arrow “B” indicates this. Arrows A and B represent the two sides of the product market. Where do households obtain the income to buy goods and services? They provide the labor and other resources (e.g., land, capital, raw materials) firms need to produce goods and services in the market for inputs (or factors of production). Arrow “C” indicates this. In return, firms pay for the inputs (or resources) they use in the form of wages and other factor payments. Arrow “D” indicates this. Arrows “C” and “D” represent the two sides of the factor market.

Of course, in the real world, there are many different markets for goods and services and markets for many different types of labor. The circular flow diagram simplifies this to make the picture easier to grasp. In the diagram, firms produce goods and services, which they sell to households in return for revenues. The outer circle shows this, and represents the two sides of the product market (for example, the market for goods and services) in which households demand and firms supply. Households sell their labor as workers to firms in return for wages, salaries, and benefits. The inner circle shows this and represents the two sides of the labor market in which households supply and firms demand.

This version of the circular flow model is stripped down to the essentials, but it has enough features to explain how the product and labor markets work in the economy. We could easily add details to this basic model if we wanted to introduce more real-world elements, like financial markets, governments, and interactions with the rest of the globe (imports and exports).

Economists carry a set of theories in their heads like a carpenter carries around a toolkit. When they see an economic issue or problem, they go through the theories they know to see if they can find one that fits. Then they use the theory to derive insights about the issue or problem. Economists express theories as diagrams, graphs, or even as mathematical equations. (Do not worry. In this course, we will mostly use graphs.) Economists do not figure out the answer to the problem first and then draw the graph to illustrate. Rather, they use the graph of the theory to help them figure out the answer. Although at the introductory level, you can sometimes figure out the right answer without applying a model, if you keep studying economics, before too long you will run into issues and problems that you will need to graph to solve. We explain both micro and macroeconomics in terms of theories and models. The most well-known theories are probably those of supply and demand, but you will learn a number of others.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Steven A. Greenlaw, David Shapiro, Daniel MacDonald

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Principles of Economics 3e

- Publication date: Dec 14, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-3-how-economists-use-theories-and-models-to-understand-economic-issues

© Jan 23, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Economic Glossary

- Depression Defined

- Introduction to Economics

- Microeconomics

- Macroeconomics

Economic Definition of hypothesis . Defined.

Offline Version : PDF

Term hypothesis Definition : A reasonable proposition about the workings of the world that's inspired or implied by a theory and which may or may not be true. An hypothesis is essentially a prediction made by a theory that can be compared with observations in the real world. Hypotheses usually take the form: "If A, the also B." The essence of the scientific method is to test, or verify, hypotheses against real world data. If supported by data over and over again, hypotheses become principles.

« hyperinflation | hysteresis »

Permalink : https://glossary.econguru.com/economic-term/hypothesis

Alphabetical Reference to Over 2,000 Economic Terms

© 2007, 2008 Glossary.EconGuru.com . All rights reserved. Privacy Policy | Terms of Use | Disclaimer | Contact Us

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.5: Economic Models

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 3432

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Math Review

Mathematical economics uses mathematical methods, such as algebra and calculus, to represent theories and analyze problems in economics.

Learning objectives

Review basic algebra and calculus’ concepts relevant in introductory economics

As a social science, economics analyzes the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. The study of economics requires the use of mathematics in order to analyze and synthesize complex information.

Mathematical Economics

Mathematical economics is the application of mathematical methods to represent theories and analyze problems in economics. Using mathematics allows economists to form meaningful, testable propositions about complex subjects that would be hard to express informally. Math enables economists to make specific and positive claims that are supported through formulas, models, and graphs. Mathematical disciplines, such as algebra and calculus, allow economists to study complex information and clarify assumptions.

Algebra is the study of operations and their application to solving equations. It provides structure and a definite direction for economists when they are analyzing complex data. Math deals with specified numbers, while algebra introduces quantities without fixed numbers (known as variables). Using variables to denote quantities allows general relationships between quantities to be expressed concisely. Quantitative results in science, economics included, are expressed using algebraic equations.

Concepts in algebra that are used in economics include variables and algebraic expressions. Variables are letters that represent general, non-specified numbers. Variables are useful because they can represent numbers whose values are not yet known, they allow for the description of general problems without giving quantities, they allow for the description of relationships between quantities that may vary, and they allow for the description of mathematical properties. Algebraic expressions can be simplified using basic math operations including addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and exponentiation.

In economics, theories need the flexibility to formulate and use general structures. By using algebra, economists are able to develop theories and structures that can be used with different scenarios regardless of specific quantities.

- Calculus is the mathematical study of change. Economists use calculus in order to study economic change whether it involves the world or human behavior.

Calculus has two main branches:

- Differential calculus is the study of the definition, properties, and applications of the derivative of a function (rates of change and slopes of curves). By finding the derivative of a function, you can find the rate of change of the original function.

- Integral calculus is the study of the definitions, properties, and applications of two related concepts, the indefinite and definite integral (accumulation of quantities and the areas under curves).

Calculus is widely used in economics and has the ability to solve many problems that algebra cannot. In economics, calculus is used to study and record complex information – commonly on graphs and curves. Calculus allows for the determination of a maximal profit by providing an easy way to calculate marginal cost and marginal revenue. It can also be used to study supply and demand curves.

Common Mathematical Terms

Economics utilizes a number of mathematical concepts on a regular basis such as:

- Dependent Variable: The output or the effect variable. Typically represented as yy, the dependent variable is graphed on the yy-axis. It is the variable whose change you are interested in seeing when you change other variables.

- Independent or Explanatory Variable: The inputs or causes. Typically represented as x1x1 , x2x2 , x3x3, etc., the independent variables are graphed on the xx-axis. These are the variables that are changed in order to see how they affect the dependent variable.

- Slope: The direction and steepness of the line on a graph. It is calculated by dividing the amount the line increases on the yy-axis (vertically) by the amount it changes on the xx-axis (horizontally). A positive slope means the line is going up toward the right on a graph, and a negative slope means the line is going down toward the right. A horizontal line has a slope of zero, while a vertical line has an undefined slope. The slope is important because it represents a rate of change.

- Tangent: The single point at which two curves touch. The derivative of a curve, for example, gives the equation of a line tangent to the curve at a given point.

Assumptions

Economists use assumptions in order to simplify economics processes so that they are easier to understand.

Assess the benefits and drawbacks of using simplifying assumptions in economics

As a field, economics deals with complex processes and studies substantial amounts of information. Economists use assumptions in order to simplify economic processes so that it is easier to understand. Simplifying assumptions are used to gain a better understanding about economic issues with regards to the world and human behavior.

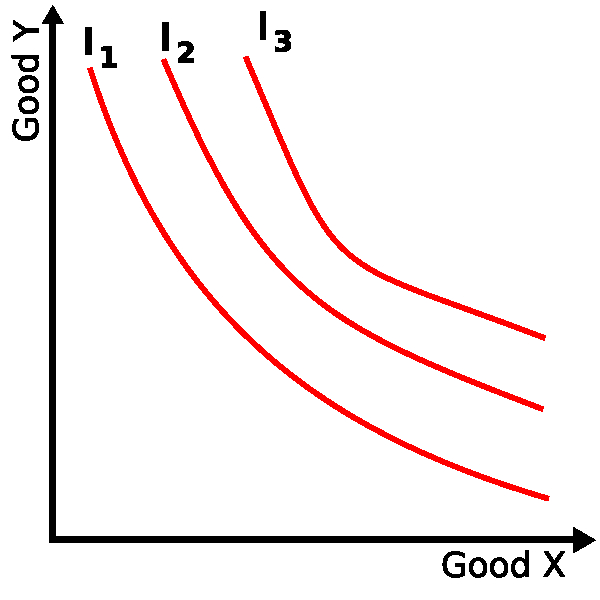

Simple indifference curve : An indifference curve is used to show potential demand patterns. It is an example of a graph that works with simplifying assumptions to gain a better understanding of the world and human behavior in relation to economics.

Economic Assumptions

Neo-classical economics works with three basic assumptions:

- People have rational preferences among outcomes that can be identified and associated with a value.

- Individuals maximize utility (as consumers) and firms maximize profit (as producers).

- People act independently on the basis of full and relevant information.

Benefits of Economic Assumptions

Assumptions provide a way for economists to simplify economic processes and make them easier to study and understand. An assumption allows an economist to break down a complex process in order to develop a theory and realm of understanding. Good simplification will allow the economists to focus only on the most relevant variables. Later, the theory can be applied to more complex scenarios for additional study.

For example, economists assume that individuals are rational and maximize their utilities. This simplifying assumption allows economists to build a structure to understand how people make choices and use resources. In reality, all people act differently. However, using the assumption that all people are rational enables economists study how people make choices.

Criticisms of Economic Assumptions

Although, simplifying assumptions help economists study complex scenarios and events, there are criticisms to using them. Critics have stated that assumptions cause economists to rely on unrealistic, unverifiable, and highly simplified information that in some cases simplifies the proofs of desired conclusions. Examples of such assumptions include perfect information, profit maximization, and rational choices. Economists use the simplified assumptions to understand complex events, but criticism increases when they base theories off the assumptions because assumptions do not always hold true. Although simplifying can lead to a better understanding of complex phenomena, critics explain that the simplified, unrealistic assumptions cannot be applied to complex, real world situations.

Hypotheses and Tests

Economics, as a science, follows the scientific method in order to study data, observe patterns, and predict results of stimuli.

Apply the steps of the scientific method to economic questions

There are specific steps that must be followed when using the scientific method. Economics follows these steps in order to study data and build principles:

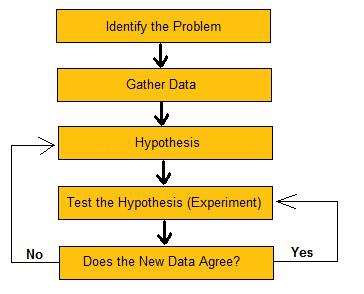

Scientific Method : The scientific method is used in economics to study data, observe patterns, and predict results.

- Identify the problem – in the case of economics, this first step of the scientific method involves determining the focus or intent of the work. What is the economist studying? What is he trying to prove or show through his work?

- Gather data – economics involves extensive amounts of data. For this reason, it is important that economists can break down and study complex information. The second step of the scientific method involves selecting the data that will be used in the study.

- Hypothesis – the third step of the scientific method involves creating a model that will be used to make sense of all of the data. A hypothesis is simply a prediction. What does the economist think the overall outcome of the study will be?

- Test hypothesis – the fourth step of the scientific method involves testing the hypothesis to determine if it is true. This is a critical stage within the scientific method. The observations must be tested to make sure they are unbiased and reproducible. In economics, extensive testing and observation is required because the outcome must be obtained more than once in order for it to be valid. It is not unusual for testing to take some time and for economists to make adjustments throughout the testing process.

- Analyze the results – the final step of the scientific method is to analyze the results. First, an economist will ask himself if the data agrees with the hypothesis. If the answer is “yes,” then the hypothesis was accurate. If the answer is “no,” then the economist must go back to the original hypothesis and adjust the study accordingly. A negative result does not mean that the study is over. It simply means that more work and analysis is required.

Observation of data is critical for economists because they take the results and interpret them in a meaningful way. Cause and effect relationships are used to establish economic theories and principles. Over time, if a theory or principle becomes accepted as universally true, it becomes a law. In general, a law is always considered to be true. The scientific method provides the framework necessary for the progression of economic study. All economic theories, principles, and laws are generalizations or abstractions. Through the use of the scientific method, economists are able to break down complex economic scenarios in order to gain a deeper understanding of critical data.

Economic Models

A model is simply a framework that is designed to show complex economic processes.

Recognize the uses and limitations of economic models

In economics, a model is defined as a theoretical construct that represents economic processes through a set of variables and a set of logical or quantitative relationships between the two. A model is simply a framework that is designed to show complex economic processes. Most models use mathematical techniques in order to investigate, theorize, and fit theories into economic situations.

Uses of an Economic Model

Economists use models in order to study and portray situations. The focus of a model is to gain a better understanding of how things work, to observe patterns, and to predict the results of stimuli. Models are based on theory and follow the rules of deductive logic.

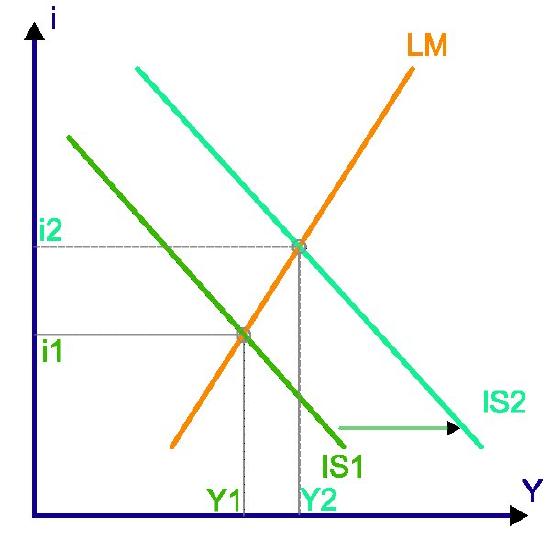

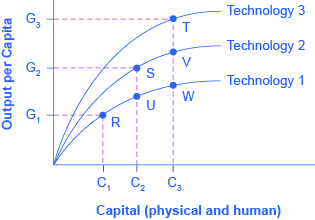

Economic model diagram : In economics, models are used in order to study and portray situations and gain a better understand of how things work.

Economic models have two functions: 1) to simplify and abstract from observed data, and 2) to serve as a means of selection of data based on a paradigm of econometric study. Economic processes are known to be enormously complex, so simplification to gain a clearer understanding is critical. Selecting the correct data is also very important because the nature of the model will determine what economic facts are studied and how they will be compiled.

- Examples of the uses of economic models include: professional academic interest, forecasting economic activity, proposing economic policy, presenting reasoned arguments to politically justify economic policy, as well as economic planning and allocation.

Constructing a Model

The construction and use of a model will vary according to the specific situation. However, creating a model does have two basic steps: 1) generate the model, and 2) checking the model for accuracy – also known as diagnostics. The diagnostic step is important because a model is only useful if the data and analysis is accurate.

Limitations of a Model

Due to the complexity of economic models, there are obviously limitations that come into account. First, all of the data provided must be complete and accurate in order for the analysis to be successful. Also, once the data is entered, it must be analyzed correctly. In most cases, economic models use mathematical or quantitative analysis. Within this realm of observation, accuracy is very important. During the construction of a model, the information will be checked and updated as needed to ensure accuracy. Some economic models also use qualitative analysis. However, this kind of analysis is known for lacking precision. Furthermore, models are fundamentally only as good as their founding assumptions.

The use of economic models is important in order to further study and understand economic processes. Steps must be taken throughout the construction of the model to ensure that the data provided and analyzed is correct.

Normative and Positive Economics

Positive economics is defined as the “what is” of economics, while normative economics focuses on the “what ought to be”.

Contrast normative and positive statements about economic policy

Positive and normative economic thought are two specific branches of economic reasoning. Although they are associated with one another, positive and normative economic thought have different focuses when analyzing economic scenarios.

Positive Economics

Positive economics is a branch of economics that focuses on the description and explanation of phenomena, as well as their casual relationships. It focuses primarily on facts and cause-and-effect behavioral relationships, including developing and testing economic theories. As a science, positive economics focuses on analyzing economic behavior. It avoids economic value judgments. For example, positive economic theory would describe how money supply growth impacts inflation, but it does not provide any guidance on what policy should be followed. “The unemployment rate in France is higher than that in the United States” is a positive economic statement. It gives an overview of an economic situation without providing any guidance for necessary actions to address the issue.

Normative Economics

Normative economics is a branch of economics that expresses value or normative judgments about economic fairness. It focuses on what the outcome of the economy or goals of public policy should be. Many normative judgments are conditional. They are given up if facts or knowledge of facts change. In this instance, a change in values is seen as being purely scientific. Welfare economist Amartya Sen explained that basic (normative) judgments rely on knowledge of facts.

An example of a normative economic statement is “The price of milk should be $6 a gallon to give dairy farmers a higher living standard and to save the family farm. ” It is a normative statement because it reflects value judgments. It states facts, but also explains what should be done. Normative economics has subfields that provide further scientific study including social choice theory, cooperative game theory, and mechanism design.

Relationship Between Positive and Normative Economics

Positive economics does impact normative economics because it ranks economic policies or outcomes based on acceptability (normative economics). Positive economics is defined as the “what is” of economics, while normative economics focuses on the “what ought to be. ” Positive economics is utilized as a practical tool for achieving normative objectives. In other words, positive economics clearly states an economic issue and normative economics provides the value-based solution for the issue.

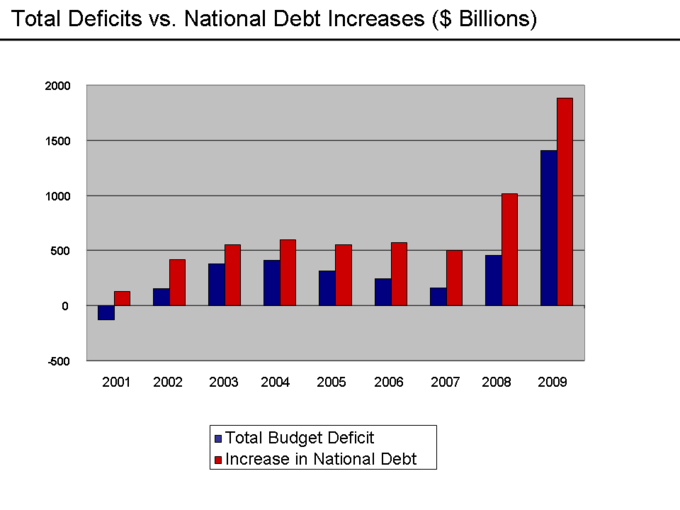

Debt Increases : This graph shows the debt increases in the United States from 2001-2009. Positive economics would provide a statement saying that the debt has increased. Normative economics would state what needs to be done in order to work towards resolving the issue of increasing debt.

- Using mathematics allows economists to form meaningful, testable propositions about complex subjects that would be hard to express informally.

- Algebra is the study of operations and their application to solving equations. It provides structure and a definite direction for economists when they are analyzing complex data.

- Concepts in algebra that are used in economics include variables and algebraic expressions.

- In economics, calculus is used to study and record complex information – commonly on graphs and curves.

- Neo-classical economics employs three basic assumptions: people have rational preferences among outcomes that can be identified and associated with a value, individuals maximize utility and firms maximize profit, and people act independently on the basis of full and relevant information.

- An assumption allows an economist to break down a complex process in order to develop a theory and realm of understanding. Later, the theory can be applied to more complex scenarios for additional study.

- Critics have stated that assumptions cause economists to rely on unrealistic, unverifiable, and highly simplified information that in some cases simplifies the proofs of desired conclusions.

- Although simplifying can lead to a better understanding of complex phenomena, critics explain that the simplified, unrealistic assumptions cannot be applied to complex, real world situations.

- The scientific method involves identifying a problem, gathering data, forming a hypothesis, testing the hypothesis, and analyzing the results.

- A hypothesis is simply a prediction.

- In economics, extensive testing and observation is required because the outcome must be obtained more than once in order to be valid.

- Cause and effect relationships are used to establish economic theories and principles. Over time, if a theory or principle becomes accepted as universally true, it becomes a law. In general, a law is always considered to be true.

- The scientific method provides the framework necessary for the progression of economic study.

- Many models use mathematical techniques in order to investigate, theorize, and fit theories into economic situations.

- Economic models have two functions: 1) to simplify and abstract from observed data, and 2) to serve as a means of selection of data based on a paradigm of econometric study.

- Creating a model has two basic steps: 1) generate the model, and 2) checking the model for accuracy – also known as diagnostics.

- Positive economics is a branch of economics that focuses on the description and explanation of phenomena, as well as their casual relationships.

- Positive economics clearly states an economic issue and normative economics provides the value-based solution for the issue.

- Normative economics is a branch of economics that expresses value or normative judgments about economic fairness. It focuses on what the outcome of the economy or goals of public policy should be.

- Positive economics does impact normative economics because it ranks economic polices or outcomes based on acceptability (normative economics).

- quantitative : Of a measurement based on some number rather than on some quality.

- variable : something whose value may be dictated or discovered.

- assumption : The act of taking for granted, or supposing a thing without proof; a supposition; an unwarrantable claim.

- simplify : To make simpler, either by reducing in complexity, reducing to component parts, or making easier to understand.

- hypothesis : An assumption taken to be true for the purpose of argument or investigation.

- deductive : Based on inferences from general principles.

- diagnostics : The process of determining the state of or capability of a component to perform its function(s).

- qualitative : Based on descriptions or distinctions rather than on some quantity.

- normative economics : Economic thought in which one applies moral beliefs, or judgment, claiming that an outcome is “good” or “bad”.

- positive economics : The description and explanation of economic phenomena and their causal relationships.

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SPECIFIC ATTRIBUTION

- Economics. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Economics . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Elementary algebra. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Elementary_algebra . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mathematical economics. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Mathematical_economics . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Calculus. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Calculu...ntial_calculus . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Dependent variable. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Depende...ndent_variable . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Tangent. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Tangent . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Slope. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Slope . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- variable. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/variable . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- quantitative. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/quantitative . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Neo-classical economics. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Neo-classical_economics . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Economics. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Economi...of_assumptions . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- simplify. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/simplify . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- assumption. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/assumption . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Simple-indifference-curves. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Si...nce-curves.svg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Scientific Method. Provided by : Wikibooks. Located at : en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Scientific_Method . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Principles of Economics/Economic Modeling. Provided by : Wikibooks. Located at : en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Princip...nomic_Modeling . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Scientific Method/Independent and Dependent Variables. Provided by : Wikibooks. Located at : en.wikibooks.org/wiki/The_Sci...dent_Variables . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- hypothesis. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/hypothesis . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Scientific Method. Provided by : Wikimedia. Located at : commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi...fic_Method.jpg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Economic model. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Economic_model . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- diagnostics. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/diagnostics . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- deductive. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/deductive . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- qualitative. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/qualitative . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Islm. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Islm.svg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- positive economics. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/positive_economics . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- normative economics. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/normative_economics . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Value (economics). Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Value_(economics) . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Positive economics. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Positive_economics . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Normative economics. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Normative_economics . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Deficits vs.nDebt Increases - 2009. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Deficits_vs._Debt_Increases_-_2009.png . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Philosophy of Economics

“Philosophy of Economics” consists of inquiries concerning (a) rational choice, (b) the appraisal of economic outcomes, institutions and processes, and (c) the ontology of economic phenomena and the possibilities of acquiring knowledge of them. Although these inquiries overlap in many ways, it is useful to divide philosophy of economics in this way into three subject matters which can be regarded respectively as branches of action theory, ethics (or normative social and political philosophy), and philosophy of science. Economic theories of rationality, welfare, and social choice defend substantive philosophical theses often informed by relevant philosophical literature and of evident interest to those interested in action theory, philosophical psychology, and social and political philosophy. Economics is of particular interest to those interested in epistemology and philosophy of science both because of its detailed peculiarities and because it possesses many of the overt features of the natural sciences, while its object consists of social phenomena.

1.1 The emergence of economics and of economies

1.2 contemporary economics and its several schools, 2.1 positive versus normative economics, 2.2 reasons versus causes, 2.3 social scientific naturalism, 2.4 abstraction, idealization, and ceteris paribus clauses in economics, 2.5 causation in economics and econometrics, 2.6 structure and strategy of economics: paradigms and research programmes, 3.1 classical economics and the method a priori, 3.2 friedman and the defense of “unrealistic assumptions”, 4.1 popperian approaches, 4.2 the rhetoric of economics, 4.3 “realism” in economic methodology, 4.4 economic methodology and social studies of science, 4.5 case studies, 5.1 individual rationality, 5.2 collective rationality and social choice, 5.3 game theory, 6.1 welfare, 6.2 efficiency, 6.3 other directions in normative economics, 7. conclusions, economic methodology, ethics and economics, rationality, other works cited, related entries, 1. introduction: what is economics.

Both the definition and the precise domain of economics are subjects of controversy within philosophy of economics. At first glance, the difficulties in defining economics may not appear serious. Economics is, after all, concerned with aspects of the production, exchange, distribution, and consumption of commodities and services. But this claim and the terms it contains are vague; and it is arguable that economics is relevant to a great deal more. It helps to approach the question, “What is economics?” historically, before turning to comments on contemporary features of the discipline.

Philosophical reflection on economics is ancient, but the conception of the economy as a distinct object of study dates back only to the 18th century. Aristotle addresses some problems that most would recognize as pertaining to economics, mainly as problems concerning how to manage a household. Scholastic philosophers addressed ethical questions concerning economic behavior, and they condemned usury — that is, the taking of interest on money. With the increasing importance of trade and of nation-states in the early modern period, ‘mercantilist’ philosophers and pamphleteers were largely concerned with the balance of trade and the regulation of the currency. There was an increasing recognition of the complexities of the financial management of the state and of the possibility that the way that the state taxed and acted influenced the production of wealth.

In the early modern period, those who reflected on the sources of a country’s wealth recognized that the annual harvest, the quantities of goods manufactured, and the products of mines and fisheries depend on facts about nature, individual labor and enterprise, tools and what we would call “capital goods”, and state and social regulations. Trade also seemed advantageous, at least if the terms were good enough. It took no conceptual leap to recognize that manufacturing and farming could be improved and that some taxes and tariffs might be less harmful to productive activities than others. But to formulate the idea that there is such a thing as “the economy” with regularities that can be investigated requires a bold further step. In order for there to be an object of inquiry, there must be regularities in production and exchange; and for the inquiry to be non-trivial, these regularities must go beyond what is obvious to the producers, consumers, and exchangers themselves. Only in the eighteenth century, most clearly illustrated by the work of Cantillon, the physiocrats, David Hume , and especially Adam Smith (see the entry on Smith’s moral and political philosophy ), does one find the idea that there are laws to be discovered that govern the complex set of interactions that produce and distribute consumption goods and the resources and tools that produce them (Backhouse 2002).

Crucial to the possibility of a social object of scientific inquiry is the idea of tracing out the unintended consequences of the intentional actions of individuals. Thus, for example, Hume traces the rise in prices and the temporary increase in economic activity that follow an increase in currency to the perceptions and actions of individuals who first spend the additional currency (1752). In spending their additional gold imported from abroad, traders do not intend to increase the price level. But that is what they do nevertheless. Adam Smith expands and perfects this insight and offers a systematic Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations . From his account of the demise of feudalism (1776, Book II, Ch. 4) to his famous discussion of the invisible hand, Smith emphasizes unintended consequences. “[H]e intends only his own gain; and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest, he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it” (1776, Book IV, Ch. 2). The existence of regularities, which are the unintended consequences of individual choices gives rise to an object of scientific investigation.

One can distinguish the domain of economics from the domain of other social scientific inquiries either by specifying some set of causal factors or by specifying some range of phenomena. The phenomena with which economists are concerned are production, consumption, distribution and exchange—particularly via markets. But since so many different causal factors are relevant to these, including the laws of thermodynamics, metallurgy, geography and social norms, even the laws governing digestion, economics cannot be distinguished from other inquiries only by the phenomena it studies. Some reference to a set of central causal factors is needed. Thus, for example, John Stuart Mill maintained that, “Political economy…[is concerned with] such of the phenomena of the social state as take place in consequence of the pursuit of wealth. It makes entire abstraction of every other human passion or motive, except those which may be regarded as perpetually antagonising principles to the desire of wealth, namely aversion to labour, and desire of the present enjoyment of costly indulgences.” (1843, Book VI, Chapter 9, Section 3) In Mill’s view, economics is mainly concerned with the consequences of individual pursuit of tangible wealth, though it takes some account of less significant motives such as aversion to labor.

Mill takes it for granted that individuals act rationally in their pursuit of wealth and luxury and avoidance of labor, rather than in a disjointed or erratic way, but he has no theory of consumption, or explicit theory of rational economic choice, and his theory of resource allocation is rather thin. These gaps were gradually filled during the so-called neoclassical or marginalist revolution, which linked choice of some object of consumption (and its price) not to its total utility but to its marginal utility. For example, water is obviously extremely useful, but in much of the world it is plentiful enough that another glass more or less matters little to an agent. So water is cheap. Early “neoclassical” economists such as William Stanley Jevons held that agents make consumption choices so as to maximize their own happiness (1871). This implies that they distribute their expenditures so that a dollar’s worth of water or porridge or upholstery makes the same contribution to their happiness. The “marginal utility” of a dollar’s worth of each good is the same.

In the Twentieth Century, economists stripped this theory of its hedonistic clothing (Pareto 1909, Hicks and Allen 1934). Rather than supposing that all consumption choices can be ranked by how much they promote an agent’s happiness, economists focused on the ranking itself. All that they suppose concerning evaluations is that agents are able consistently to rank the alternatives they face. This is equivalent to supposing first that rankings are complete — that is, for any two alternatives x and y that the agent considers, either the agent ranks x above y (prefers x to y ), or the agent prefers y to x , or the agent is indifferent. Second, economists suppose that agent’s rankings of alternatives (preferences) are transitive. To say that an agent’s preferences are transitive is to claim that if the agent prefers x to y and y to z , then the agent prefers x to z , with similar claims concerning indifference and combinations of indifference and preference. Though there are further technical conditions to extend the theory to infinite sets of alternatives and to capture further plausible rationality conditions concerning gambles, economists generally subscribe to a view of rational agents as at least possessing complete and transitive preferences and as choosing among the feasible alternatives whichever they most prefer. In the theory of revealed preference, economists have attempted unsuccessfully to eliminate all reference to subjective preference or to define preference in terms of choices (Samuelson 1947, Houtthaker 1950, Little 1957, Sen 1971, 1973, Hausman 2012, chapter 3).

In clarifying the view of rationality that characterizes economic agents, economists have for the most part continued to distinguish economics from other social inquiries by the content of the motives or preferences with which it is concerned. So even though people may seek happiness through asceticism, or they may rationally prefer to sacrifice all their worldly goods to a political cause, economists have supposed that such preferences are rare and unimportant to economics. Economists are concerned with the phenomena deriving from rationality coupled with a desire for wealth and for larger bundles of goods and services.

Economists have flirted with a less substantive characterization of individual motivation and with a more expansive view of the domain of economics. In his influential monograph, An Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science , Lionel Robbins defined economics as “the science which studies human behavior as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses” (1932, p. 15). According to Robbins, economics is not concerned with production, exchange, distribution, or consumption as such. It is instead concerned with an aspect of all human action. Robbins’ definition helps one to understand efforts to apply economic concepts, models, and techniques to other subject matters such as the analysis of voting behavior and legislation, even as economics maintains its connection to a traditional domain.

Contemporary economics is diverse. There are many schools and many branches. Even so-called “orthodox” or “mainstream” economics has many variants. Some mainstream economics is highly theoretical, though most of it is applied and relies on rudimentary theory. Theoretical and applied work can be distinguished as microeconomics or macroeconomics. There is also a third branch, econometrics which is devoted to the empirical estimation, elaboration, and to some extent testing of microeconomic and macroeconomic models (but see Summers 1991 and Hoover 1994).

Microeconomics focuses on relations among individuals (with firms and households frequently counting as honorary individuals and little said about the idiosyncrasies of the demand of particular individuals). Individuals have complete and transitive preferences that govern their choices. Consumers prefer more commodities to fewer and have “diminishing marginal rates of substitution” — i. e. they will pay less for units of a commodity when they already have lots of it than when they have little of it. Firms attempt to maximize profits in the face of diminishing returns: holding fixed all the inputs into production except one, output increases when there is more of the remaining input, but at a diminishing rate. Economists idealize and suppose that in competitive markets, firms and individuals cannot influence prices, but economists are also interested in strategic interactions, in which the rational choices of separate individuals are interdependent. Game theory, which is devoted to the study of strategic interactions, is of growing importance in economics. Economists model the outcome of the profit-maximizing activities of firms and the attempts of consumers optimally to satisfy their preferences as an equilibrium in which there is no excess demand on any market. What this means is that anyone who wants to buy anything at the going market price is able to do so. There is no excess demand, and unless a good is free, there is no excess supply.

Macroeconomics grapples with the relations among economic aggregates, such as relations between the money supply and the rate of interest or the rate of growth, focusing especially on problems concerning the business cycle and the influence of monetary and fiscal policy on economic outcomes. Many mainstream economists would like to unify macroeconomics and microeconomics, but few economists are satisfied with the attempts that have been made to do so, especially via so called “representative agents” (Kirman 1992, Hoover 2001a). Macroeconomics is immediately relevant to economic policy and hence (and unsurprisingly) subject to much more heated (and politically-charged) controversy than microeconomics or econometrics. Schools of macroeconomics include Keynesians (and “new-Keynesians”), monetarists, “new classical economics” (rational expectations theory — Begg 1982, Carter and Maddock 1984, Hoover 1988, Minford and Peel 1983), and “real business cycle” theories (Kydland and Prescott 1991, 1994; Sent 1998).

Branches of mainstream economics are also devoted to specific questions concerning growth, finance, employment, agriculture, housing, natural resources, international trade, and so forth. Within orthodox economics, there are also many different approaches, such as agency theory (Jensen and Meckling 1976, Fama 1980), the Chicago school (Becker 1976), or public choice theory (Brennan and Buchanan 1985, Buchanan 1975). These address questions concerning incentives within firms and families and the ways that institutions guide choices.

Although mainstream economics is dominant and demands the most attention, there are many other schools. Austrian economists accept orthodox views of choices and constraints, but they emphasize uncertainty and question whether one should regard outcomes as equilibria, and they are skeptical about the value of mathematical modeling (Buchanan and Vanberg 1989, Dolan 1976, Kirzner 1976, Mises 1949, 1978, 1981, Rothbard 1957, Wiseman 1983, Boettke 2010, Holcombe 2014, Nell 2014a, 2014b, 2017, Boettke and Coyne 2015, Hagedorn 2015, Horwitz 2015, Dekker 2016, Linsbichler 2017 ).

Traditional institutionalist economists question the value of abstract general theorizing and emphasize evolutionary concepts (Dugger 1979, Wilber and Harrison 1978, Wisman and Rozansky 1991, Hodgson 2000, 2013, 2016, Hodgson and Knudsen 2010, Delorme 2010, Richter 2015). They emphasize the importance of generalizations concerning norms and behavior within particular institutions. Applied work in institutional economics is sometimes very similar to applied orthodox economics. More recent work in economics, which is also called institutionalist, attempts to explain features of institutions by emphasizing the costs of transactions, the inevitable incompleteness of contracts, and the problems “principals” face in monitoring and directing their agents (Coase 1937; Williamson 1985; Mäki et al. 1993, North 1990; Brousseau and Glachant 2008).

Marxian and socialist economists traditionally articulated and developed Karl Marx’s economic theories, but recently many socialist economists have revised traditional Marxian concepts and themes with tools borrowed from orthodox economic theory (Morishima 1973, Roemer 1981, 1982, Bowles 2012, Piketty 2014, Lebowitz 2015, Auerbach 2016, Beckert 2016, Jacobs and Mazzucato 2016).

There are also socio-economists , who are concerned with the norms that govern choices (Etzioni 1988, 2018), behavioral economists , who study the nitty-gritty of choice behavior (Winter 1962, Thaler 1994, Ben Ner and Putterman 1998, Kahneman and Tversky 2000, Camerer 2003, Camerer and Loewenstein 2003, Camerer et al. 2003, Loewenstein 2008, Thaler and Sunstein 2008, Saint-Paul 2011, Oliver 2013), post-Keynesians , who look to Keynes’s work and especially his emphasis on demand (Dow 1985, Kregel 1976, Harcourt and Kriesler 2013 Rochon and Rossi 2017), evolutionary economists , who emphasize the importance of institutions (Witt 2008, Hodgson and Knudsen 2010, Vromen 2009, Hodgson 2013, 2016, Carsten 2013, Dopfer and Potts 2014, Wilson and Kirman 2016), neo-Ricardians , who emphasize relations among economic classes (Sraffa 1960, Pasinetti 1981, Roncaglia 1978), and even neuroeconomists , who study neurological concomitants of choice behavior (Camerer 2007, Camerer et al. 2005, Camerer et al. 2008, Glimcher et al. 2008, Loewenstein et al. 2008, Rusticinni 2005, 2008, Glimcher 2010). Economics is not one homogeneous enterprise.

2. Six central methodological problems

Although the different branches and schools of economics raise a wide variety of epistemological and ontological issues concerning economics, six problems have been central to methodological reflection (in this philosophical sense) concerning economics:

Policy makers look to economics to guide policy, and it seems inevitable that even the most esoteric issues in theoretical economics may bear on some people’s material interests. The extent to which economics bears on and may be influenced by normative concerns raises methodological questions about the relationships between a positive science concerning “facts” and a normative inquiry into values and what ought to be. Most economists and methodologists believe that there is a reasonably clear distinction between facts and values, between what is and what ought to be, and they believe that most of economics should be regarded as a positive science that helps policy makers choose means to accomplish their ends, though it does not bear on the choice of ends itself.

This view is questionable for several reasons (Mongin 2006, Hausman, McPherson, and Satz 2017). First, economists have to interpret and articulate the incomplete specifications of goals and constraints provided by policy makers (Machlup 1969b). Second, economic “science” is a human activity, and like all human activities, it is governed by values. Those values need not be the same as the values that influence economic policy, but it is debatable whether the values that govern the activity of economists can be sharply distinguished from the values that govern policy makers. Third, much of economics is built around a normative theory of rationality. One can question whether the values implicit in such theories are sharply distinguishable from the values that govern policies. For example, it may be difficult to hold a maximizing view of individual rationality, while at the same time insisting that social policy should resist maximizing growth, wealth, or welfare in the name of freedom, rights, or equality. Fourth, people’s views of what is right and wrong are, as a matter of fact, influenced by their beliefs about how people in fact behave. There is evidence that studying theories that depict individuals as self-interested leads people to regard self-interested behavior more favorably and to become more self-interested (Marwell and Ames 1981, Frank et al . 1993). Finally, people’s judgments are clouded by their interests. Since economic theories bear so centrally on people’s interests, there are bound to be ideological biases at work in the discipline (Marx 1867, Preface). Positive and normative are especially interlinked within economics, because economists are not all researchers and teachers. In addition, economists work as commentators and as it were “hired guns” whose salaries depend on arriving at the conclusions their employers want. The bitter polemics concerning macroeconomic policy responses to the great recession beginning in 2008 testify to the influence of ideology.

Orthodox theoretical microeconomics is as much a theory of rational choices as it a theory that explains and predicts economic outcomes. Since virtually all economic theories that discuss individual choices take individuals as acting for reasons, and thus in some way rational, questions about the role that views of rationality and reasons should play in economics are of general importance. Economists are typically concerned with the aggregate results of individual choices rather than with the actions of particular individuals, but their theories in fact offer both causal explanations for why individuals choose as they do and accounts of the reasons for their choices. See also the entries on methodological individualism and reasons for action: justification, motivation, explanation .

Explanations in terms of reasons have several features that distinguish them from explanations in terms of causes. Reasons purport to justify the actions they explain, and indeed so called “external reasons” (Williams 1981) only justify action, without purporting to explain it. Reasons can be evaluated, and they are responsive to criticism. Reasons, unlike causes, must be intelligible to those for whom they are reasons. On grounds such as these, many philosophers have questioned whether explanations of human action can be causal explanations (von Wright 1971, Winch 1958). Yet merely giving a reason — even an extremely good reason — fails to explain an agent’s action, if the reason was not in fact “effective.” Someone might, for example, start attending church regularly and give as his reason a concern with salvation. But others might suspect that this agent is deceiving himself and that the minister’s attractive daughter is in fact responsible for his renewed interest in religion. Donald Davidson (1963) argued that what distinguishes the reasons that explain an action from the reasons that fail to explain it is that the former are also causes of the action. Although the account of rationality within economics differs in some ways from the folk psychology people tacitly invoke in everyday explanations of actions, many of the same questions carry over (Rosenberg 1976, ch. 5; 1980, Hausman 2012).

An additional difference between explanations in terms of reasons and explanations in terms of causes, which some economists have emphasized, is that the beliefs and preferences that explain actions may depend on mistakes and ignorance (Knight 1935). As a first approximation, economists can abstract from such difficulties caused by the intentionality of belief and desire. They thus often assume that people have perfect information about all the relevant facts. In that way theorists need not worry about what people’s beliefs are. (If people have perfect information, then they believe and expect whatever the facts are.) But once one goes beyond this first approximation, difficulties arise which have no parallel in the natural sciences. Choice depends on how things look “from the inside”, which may be very different from the actual state of affairs. Consider for example the stock market. The “true” value of a stock depends on the future profits of the company, which are of course uncertain. In 2006 house prices in the U.S. were extremely inflated. But whether they were “too high” depended at least in the short run, on what people believe. They were excellent investments if one could sell them to others who would be willing to pay even more for them. Economists disagree about how significant this subjectivity is. Members of the Austrian school argue that these differences are of great importance and sharply distinguish theorizing about economics from theorizing about any of the natural sciences (Buchanan and Vanberg 1989, von Mises 1981).

Of all the social sciences, economics most closely resembles the natural sciences. Economic theories have been axiomatized, and articles and books of economics are full of theorems. Of all the social sciences, only economics boasts an ersatz Nobel Prize. Economics is thus a test case for those concerned with the extent of the similarities between the natural and social sciences. Those who have wondered whether social sciences must differ fundamentally from the natural sciences seem to have been concerned mainly with three questions:

(i) Are there fundamental differences between the structure or concepts of theories and explanations in the natural and social sciences? Some of these issues were already mentioned in the discussion above of reasons versus causes.

(ii) Are there fundamental differences in goals? Philosophers and economists have argued that in addition to or instead of the predictive and explanatory goals of the natural sciences, the social sciences should aim at providing us with understanding . Weber and others have argued that the social sciences should provide us with an understanding “from the inside”, that we should be able to empathize with the reactions of the agents and to find what happens “understandable” (Weber 1904, Knight 1935, Machlup 1969a). This (and the closely related recognition that explanations cite reasons rather than just causes) seems to introduce an element of subjectivity into the social sciences that is not found in the natural sciences.

(iii) Owing to the importance of human choices (or perhaps free will), are social phenomena too irregular to be captured within a framework of laws and theories? Given human free will, perhaps human behavior is intrinsically unpredictable and not subject to any laws. But there are, in fact, many regularities in human action, and given the enormous causal complexity characterizing some natural systems, the natural sciences must cope with many irregularities, too.

Economics raises questions concerning the legitimacy of severe abstraction and idealization. For example, mainstream economic models often stipulate that everyone is perfectly rational and has perfect information or that commodities are infinitely divisible. Such claims are exaggerations, and they are clearly false. Other schools of economics may not employ idealizations that are this extreme, but there is no way to do economics if one is not willing to simplify drastically and abstract from many complications. How much simplification, idealization, abstraction or “isolation” (Mäki 2006) is legitimate?

In addition, because economists attempt to study economic phenomena as constituting a separate domain, influenced only by a small number of causal factors, the claims of economics are true only ceteris paribus — that is, they are true only if there are no interferences or disturbing causes. What are ceteris paribus clauses, and when if ever are they legitimate in science? Questions concerning ceteris paribus clauses are closely related to questions concerning simplifications and idealizations, since one way to simplify is to suppose that the various disturbing causes or interferences are inactive and to explore the consequences of some small number of causal factors. These issues and the related question of how well supported economics is by the evidence have been the central questions in economic methodology. They will be discussed further below mainly in Section 3 .