- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Writing a Paper: Thesis Statements

Basics of thesis statements.

The thesis statement is the brief articulation of your paper's central argument and purpose. You might hear it referred to as simply a "thesis." Every scholarly paper should have a thesis statement, and strong thesis statements are concise, specific, and arguable. Concise means the thesis is short: perhaps one or two sentences for a shorter paper. Specific means the thesis deals with a narrow and focused topic, appropriate to the paper's length. Arguable means that a scholar in your field could disagree (or perhaps already has!).

Strong thesis statements address specific intellectual questions, have clear positions, and use a structure that reflects the overall structure of the paper. Read on to learn more about constructing a strong thesis statement.

Being Specific

This thesis statement has no specific argument:

Needs Improvement: In this essay, I will examine two scholarly articles to find similarities and differences.

This statement is concise, but it is neither specific nor arguable—a reader might wonder, "Which scholarly articles? What is the topic of this paper? What field is the author writing in?" Additionally, the purpose of the paper—to "examine…to find similarities and differences" is not of a scholarly level. Identifying similarities and differences is a good first step, but strong academic argument goes further, analyzing what those similarities and differences might mean or imply.

Better: In this essay, I will argue that Bowler's (2003) autocratic management style, when coupled with Smith's (2007) theory of social cognition, can reduce the expenses associated with employee turnover.

The new revision here is still concise, as well as specific and arguable. We can see that it is specific because the writer is mentioning (a) concrete ideas and (b) exact authors. We can also gather the field (business) and the topic (management and employee turnover). The statement is arguable because the student goes beyond merely comparing; he or she draws conclusions from that comparison ("can reduce the expenses associated with employee turnover").

Making a Unique Argument

This thesis draft repeats the language of the writing prompt without making a unique argument:

Needs Improvement: The purpose of this essay is to monitor, assess, and evaluate an educational program for its strengths and weaknesses. Then, I will provide suggestions for improvement.

You can see here that the student has simply stated the paper's assignment, without articulating specifically how he or she will address it. The student can correct this error simply by phrasing the thesis statement as a specific answer to the assignment prompt.

Better: Through a series of student interviews, I found that Kennedy High School's antibullying program was ineffective. In order to address issues of conflict between students, I argue that Kennedy High School should embrace policies outlined by the California Department of Education (2010).

Words like "ineffective" and "argue" show here that the student has clearly thought through the assignment and analyzed the material; he or she is putting forth a specific and debatable position. The concrete information ("student interviews," "antibullying") further prepares the reader for the body of the paper and demonstrates how the student has addressed the assignment prompt without just restating that language.

Creating a Debate

This thesis statement includes only obvious fact or plot summary instead of argument:

Needs Improvement: Leadership is an important quality in nurse educators.

A good strategy to determine if your thesis statement is too broad (and therefore, not arguable) is to ask yourself, "Would a scholar in my field disagree with this point?" Here, we can see easily that no scholar is likely to argue that leadership is an unimportant quality in nurse educators. The student needs to come up with a more arguable claim, and probably a narrower one; remember that a short paper needs a more focused topic than a dissertation.

Better: Roderick's (2009) theory of participatory leadership is particularly appropriate to nurse educators working within the emergency medicine field, where students benefit most from collegial and kinesthetic learning.

Here, the student has identified a particular type of leadership ("participatory leadership"), narrowing the topic, and has made an arguable claim (this type of leadership is "appropriate" to a specific type of nurse educator). Conceivably, a scholar in the nursing field might disagree with this approach. The student's paper can now proceed, providing specific pieces of evidence to support the arguable central claim.

Choosing the Right Words

This thesis statement uses large or scholarly-sounding words that have no real substance:

Needs Improvement: Scholars should work to seize metacognitive outcomes by harnessing discipline-based networks to empower collaborative infrastructures.

There are many words in this sentence that may be buzzwords in the student's field or key terms taken from other texts, but together they do not communicate a clear, specific meaning. Sometimes students think scholarly writing means constructing complex sentences using special language, but actually it's usually a stronger choice to write clear, simple sentences. When in doubt, remember that your ideas should be complex, not your sentence structure.

Better: Ecologists should work to educate the U.S. public on conservation methods by making use of local and national green organizations to create a widespread communication plan.

Notice in the revision that the field is now clear (ecology), and the language has been made much more field-specific ("conservation methods," "green organizations"), so the reader is able to see concretely the ideas the student is communicating.

Leaving Room for Discussion

This thesis statement is not capable of development or advancement in the paper:

Needs Improvement: There are always alternatives to illegal drug use.

This sample thesis statement makes a claim, but it is not a claim that will sustain extended discussion. This claim is the type of claim that might be appropriate for the conclusion of a paper, but in the beginning of the paper, the student is left with nowhere to go. What further points can be made? If there are "always alternatives" to the problem the student is identifying, then why bother developing a paper around that claim? Ideally, a thesis statement should be complex enough to explore over the length of the entire paper.

Better: The most effective treatment plan for methamphetamine addiction may be a combination of pharmacological and cognitive therapy, as argued by Baker (2008), Smith (2009), and Xavier (2011).

In the revised thesis, you can see the student make a specific, debatable claim that has the potential to generate several pages' worth of discussion. When drafting a thesis statement, think about the questions your thesis statement will generate: What follow-up inquiries might a reader have? In the first example, there are almost no additional questions implied, but the revised example allows for a good deal more exploration.

Thesis Mad Libs

If you are having trouble getting started, try using the models below to generate a rough model of a thesis statement! These models are intended for drafting purposes only and should not appear in your final work.

- In this essay, I argue ____, using ______ to assert _____.

- While scholars have often argued ______, I argue______, because_______.

- Through an analysis of ______, I argue ______, which is important because_______.

Words to Avoid and to Embrace

When drafting your thesis statement, avoid words like explore, investigate, learn, compile, summarize , and explain to describe the main purpose of your paper. These words imply a paper that summarizes or "reports," rather than synthesizing and analyzing.

Instead of the terms above, try words like argue, critique, question , and interrogate . These more analytical words may help you begin strongly, by articulating a specific, critical, scholarly position.

Read Kayla's blog post for tips on taking a stand in a well-crafted thesis statement.

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Introductions

- Next Page: Conclusions

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

An Overview of the Writing Process

Thesis statements, what this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can discover or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper .

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:.

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence somewhere in your first paragraph that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I get a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis,” a basic or main idea, an argument that you think you can support with evidence but that may need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following:

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question.

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough?

Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is, “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s o.k. to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on 19th-century America, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: Compare and contrast the reasons why the North and South fought the Civil War. You turn on the computer and type out the following:

The North and South fought the Civil War for many reasons, some of which were the same and some different.

This weak thesis restates the question without providing any additional information. You will expand on this new information in the body of the essay, but it is important that the reader know where you are heading. A reader of this weak thesis might think, “What reasons? How are they the same? How are they different?” Ask yourself these same questions and begin to compare Northern and Southern attitudes (perhaps you first think, “The South believed slavery was right, and the North thought slavery was wrong”). Now, push your comparison toward an interpretation—why did one side think slavery was right and the other side think it was wrong? You look again at the evidence, and you decide that you are going to argue that the North believed slavery was immoral while the South believed it upheld the Southern way of life. You write:

While both sides fought the Civil War over the issue of slavery, the North fought for moral reasons while the South fought to preserve its own institutions.

Now you have a working thesis! Included in this working thesis is a reason for the war and some idea of how the two sides disagreed over this reason. As you write the essay, you will probably begin to characterize these differences more precisely, and your working thesis may start to seem too vague. Maybe you decide that both sides fought for moral reasons, and that they just focused on different moral issues. You end up revising the working thesis into a final thesis that really captures the argument in your paper:

While both Northerners and Southerners believed they fought against tyranny and oppression, Northerners focused on the oppression of slaves while Southerners defended their own right to self-government.

Compare this to the original weak thesis. This final thesis presents a way of interpreting evidence that illuminates the significance of the question. Keep in mind that this is one of many possible interpretations of the Civil War—it is not the one and only right answer to the question . There isn’t one right answer; there are only strong and weak thesis statements and strong and weak uses of evidence.

Let’s look at another example. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

Why is this thesis weak? Think about what the reader would expect from the essay that follows: you will most likely provide a general, appreciative summary of Twain’s novel. The question did not ask you to summarize; it asked you to analyze. Your professor is probably not interested in your opinion of the novel; instead, she wants you to think about why it’s such a great novel— what do Huck’s adventures tell us about life, about America, about coming of age, about race relations, etc.? First, the question asks you to pick an aspect of the novel that you think is important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

Here’s a working thesis with potential: you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation; however, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal. Your reader is intrigued, but is still thinking, “So what? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?” Perhaps you are not sure yet, either. That’s fine—begin to work on comparing scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions. Eventually you will be able to clarify for yourself, and then for the reader, why this contrast matters. After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing the original version of this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find the latest publications on this topic. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

Anson, Chris M. and Robert A. Schwegler. The Longman Handbook for Writers. 2nd ed. New York: Longman, 2000.

Hairston, Maxine and John J. Ruszkiewicz. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers. 4th ed. New York: HarperCollins, 1996.

Lunsford, Andrea and Robert Connors. The St. Martin’s Handbook. 3rd ed. New York: St. Martin’s, 1995.

Rosen, Leonard J. and Laurence Behrens. The Allyn & Bacon Handbook. 3rd ed. Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 1997.

- Thesis Statements. Provided by : The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Located at : http://writingcenter.unc.edu/ . License : CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

UMGC Effective Writing Center Designing an Effective Thesis

Explore more of umgc.

- Writing Resources

Key Concepts

- A thesis is a simple sentence that combines your topic and your position on the topic.

- A thesis provides a roadmap to what follows in the paper.

- A thesis is like a wheel's hub--everything revolves around it and is attached to it.

After your prewriting activities-- such as assignment analysis and outlining--you should be ready to take the next step: writing a thesis statement. Although some of your assignments will provide a focus for you, it is still important for your college career and especially for your professional career to be able to state a satisfactory controlling idea or thesis that unifies your thoughts and materials for the reader.

Characteristics of an Effective Thesis

A thesis consists of two main parts: your overall topic and your position on that topic. Here are some example thesis statements that combine topic and position:

Sample Thesis Statements

Importance of tone.

Tone is established in the wording of your thesis, which should match the characteristics of your audience. For example, if you are a concerned citizen proposing a new law to your city's board of supervisors about drunk driving, you would not want to write this:

“It’s time to get the filthy drunks off the street and from behind the wheel: I demand that you pass a mandatory five-year license suspension for every drunk who gets caught driving. Do unto them before they do unto us!”

However, if you’re speaking at a concerned citizen’s meeting and you’re trying to rally voter support, such emotional language could help motivate your audience.

Using Your Thesis to Map Your Paper for the Reader

In academic writing, the thesis statement is often used to signal the paper's overall structure to the reader. An effective thesis allows the reader to predict what will be encountered in the support paragraphs. Here are some examples:

Use the Thesis to Map

Three potential problems to avoid.

Because your thesis is the hub of your essay, it has to be strong and effective. Here are three common pitfalls to avoid:

1. Don’t confuse an announcement with a thesis.

In an announcement, the writer declares personal intentions about the paper instead stating a thesis with clear point of view or position:

Write a Thesis, Not an Announcement

2. a statement of fact does not provide a point of view and is not a thesis..

An introduction needs a strong, clear position statement. Without one, it will be hard for you to develop your paper with relevant arguments and evidence.

Don't Confuse a Fact with a Thesis

3. avoid overly broad thesis statements.

Broad statements contain vague, general terms that do not provide a clear focus for the essay.

Use the Thesis to Provide Focus

Practice writing an effective thesis.

OK. Time to write a thesis for your paper. What is your topic? What is your position on that topic? State both clearly in a thesis sentence that helps to map your response for the reader.

Our helpful admissions advisors can help you choose an academic program to fit your career goals, estimate your transfer credits, and develop a plan for your education costs that fits your budget. If you’re a current UMGC student, please visit the Help Center .

Personal Information

Contact information, additional information.

By submitting this form, you acknowledge that you intend to sign this form electronically and that your electronic signature is the equivalent of a handwritten signature, with all the same legal and binding effect. You are giving your express written consent without obligation for UMGC to contact you regarding our educational programs and services using e-mail, phone, or text, including automated technology for calls and/or texts to the mobile number(s) provided. For more details, including how to opt out, read our privacy policy or contact an admissions advisor .

Please wait, your form is being submitted.

By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a thesis statement + examples

What is a thesis statement?

Is a thesis statement a question, how do you write a good thesis statement, how do i know if my thesis statement is good, examples of thesis statements, helpful resources on how to write a thesis statement, frequently asked questions about writing a thesis statement, related articles.

A thesis statement is the main argument of your paper or thesis.

The thesis statement is one of the most important elements of any piece of academic writing . It is a brief statement of your paper’s main argument. Essentially, you are stating what you will be writing about.

You can see your thesis statement as an answer to a question. While it also contains the question, it should really give an answer to the question with new information and not just restate or reiterate it.

Your thesis statement is part of your introduction. Learn more about how to write a good thesis introduction in our introduction guide .

A thesis statement is not a question. A statement must be arguable and provable through evidence and analysis. While your thesis might stem from a research question, it should be in the form of a statement.

Tip: A thesis statement is typically 1-2 sentences. For a longer project like a thesis, the statement may be several sentences or a paragraph.

A good thesis statement needs to do the following:

- Condense the main idea of your thesis into one or two sentences.

- Answer your project’s main research question.

- Clearly state your position in relation to the topic .

- Make an argument that requires support or evidence.

Once you have written down a thesis statement, check if it fulfills the following criteria:

- Your statement needs to be provable by evidence. As an argument, a thesis statement needs to be debatable.

- Your statement needs to be precise. Do not give away too much information in the thesis statement and do not load it with unnecessary information.

- Your statement cannot say that one solution is simply right or simply wrong as a matter of fact. You should draw upon verified facts to persuade the reader of your solution, but you cannot just declare something as right or wrong.

As previously mentioned, your thesis statement should answer a question.

If the question is:

What do you think the City of New York should do to reduce traffic congestion?

A good thesis statement restates the question and answers it:

In this paper, I will argue that the City of New York should focus on providing exclusive lanes for public transport and adaptive traffic signals to reduce traffic congestion by the year 2035.

Here is another example. If the question is:

How can we end poverty?

A good thesis statement should give more than one solution to the problem in question:

In this paper, I will argue that introducing universal basic income can help reduce poverty and positively impact the way we work.

- The Writing Center of the University of North Carolina has a list of questions to ask to see if your thesis is strong .

A thesis statement is part of the introduction of your paper. It is usually found in the first or second paragraph to let the reader know your research purpose from the beginning.

In general, a thesis statement should have one or two sentences. But the length really depends on the overall length of your project. Take a look at our guide about the length of thesis statements for more insight on this topic.

Here is a list of Thesis Statement Examples that will help you understand better how to write them.

Every good essay should include a thesis statement as part of its introduction, no matter the academic level. Of course, if you are a high school student you are not expected to have the same type of thesis as a PhD student.

Here is a great YouTube tutorial showing How To Write An Essay: Thesis Statements .

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Developing Strong Thesis Statements

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The thesis statement or main claim must be debatable

An argumentative or persuasive piece of writing must begin with a debatable thesis or claim. In other words, the thesis must be something that people could reasonably have differing opinions on. If your thesis is something that is generally agreed upon or accepted as fact then there is no reason to try to persuade people.

Example of a non-debatable thesis statement:

This thesis statement is not debatable. First, the word pollution implies that something is bad or negative in some way. Furthermore, all studies agree that pollution is a problem; they simply disagree on the impact it will have or the scope of the problem. No one could reasonably argue that pollution is unambiguously good.

Example of a debatable thesis statement:

This is an example of a debatable thesis because reasonable people could disagree with it. Some people might think that this is how we should spend the nation's money. Others might feel that we should be spending more money on education. Still others could argue that corporations, not the government, should be paying to limit pollution.

Another example of a debatable thesis statement:

In this example there is also room for disagreement between rational individuals. Some citizens might think focusing on recycling programs rather than private automobiles is the most effective strategy.

The thesis needs to be narrow

Although the scope of your paper might seem overwhelming at the start, generally the narrower the thesis the more effective your argument will be. Your thesis or claim must be supported by evidence. The broader your claim is, the more evidence you will need to convince readers that your position is right.

Example of a thesis that is too broad:

There are several reasons this statement is too broad to argue. First, what is included in the category "drugs"? Is the author talking about illegal drug use, recreational drug use (which might include alcohol and cigarettes), or all uses of medication in general? Second, in what ways are drugs detrimental? Is drug use causing deaths (and is the author equating deaths from overdoses and deaths from drug related violence)? Is drug use changing the moral climate or causing the economy to decline? Finally, what does the author mean by "society"? Is the author referring only to America or to the global population? Does the author make any distinction between the effects on children and adults? There are just too many questions that the claim leaves open. The author could not cover all of the topics listed above, yet the generality of the claim leaves all of these possibilities open to debate.

Example of a narrow or focused thesis:

In this example the topic of drugs has been narrowed down to illegal drugs and the detriment has been narrowed down to gang violence. This is a much more manageable topic.

We could narrow each debatable thesis from the previous examples in the following way:

Narrowed debatable thesis 1:

This thesis narrows the scope of the argument by specifying not just the amount of money used but also how the money could actually help to control pollution.

Narrowed debatable thesis 2:

This thesis narrows the scope of the argument by specifying not just what the focus of a national anti-pollution campaign should be but also why this is the appropriate focus.

Qualifiers such as " typically ," " generally ," " usually ," or " on average " also help to limit the scope of your claim by allowing for the almost inevitable exception to the rule.

Types of claims

Claims typically fall into one of four categories. Thinking about how you want to approach your topic, or, in other words, what type of claim you want to make, is one way to focus your thesis on one particular aspect of your broader topic.

Claims of fact or definition: These claims argue about what the definition of something is or whether something is a settled fact. Example:

Claims of cause and effect: These claims argue that one person, thing, or event caused another thing or event to occur. Example:

Claims about value: These are claims made of what something is worth, whether we value it or not, how we would rate or categorize something. Example:

Claims about solutions or policies: These are claims that argue for or against a certain solution or policy approach to a problem. Example:

Which type of claim is right for your argument? Which type of thesis or claim you use for your argument will depend on your position and knowledge of the topic, your audience, and the context of your paper. You might want to think about where you imagine your audience to be on this topic and pinpoint where you think the biggest difference in viewpoints might be. Even if you start with one type of claim you probably will be using several within the paper. Regardless of the type of claim you choose to utilize it is key to identify the controversy or debate you are addressing and to define your position early on in the paper.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Academic Writing Style

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Academic writing refers to a style of expression that researchers use to define the intellectual boundaries of their disciplines and specific areas of expertise. Characteristics of academic writing include a formal tone, use of the third-person rather than first-person perspective (usually), a clear focus on the research problem under investigation, and precise word choice. Like specialist languages adopted in other professions, such as, law or medicine, academic writing is designed to convey agreed meaning about complex ideas or concepts within a community of scholarly experts and practitioners.

Academic Writing. Writing Center. Colorado Technical College; Hartley, James. Academic Writing and Publishing: A Practical Guide . New York: Routledge, 2008; Ezza, El-Sadig Y. and Touria Drid. T eaching Academic Writing as a Discipline-Specific Skill in Higher Education . Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2020.

Importance of Good Academic Writing

The accepted form of academic writing in the social sciences can vary considerable depending on the methodological framework and the intended audience. However, most college-level research papers require careful attention to the following stylistic elements:

I. The Big Picture Unlike creative or journalistic writing, the overall structure of academic writing is formal and logical. It must be cohesive and possess a logically organized flow of ideas; this means that the various parts are connected to form a unified whole. There should be narrative links between sentences and paragraphs so that the reader is able to follow your argument. The introduction should include a description of how the rest of the paper is organized and all sources are properly cited throughout the paper.

II. Tone The overall tone refers to the attitude conveyed in a piece of writing. Throughout your paper, it is important that you present the arguments of others fairly and with an appropriate narrative tone. When presenting a position or argument that you disagree with, describe this argument accurately and without loaded or biased language. In academic writing, the author is expected to investigate the research problem from an authoritative point of view. You should, therefore, state the strengths of your arguments confidently, using language that is neutral, not confrontational or dismissive.

III. Diction Diction refers to the choice of words you use. Awareness of the words you use is important because words that have almost the same denotation [dictionary definition] can have very different connotations [implied meanings]. This is particularly true in academic writing because words and terminology can evolve a nuanced meaning that describes a particular idea, concept, or phenomenon derived from the epistemological culture of that discipline [e.g., the concept of rational choice in political science]. Therefore, use concrete words [not general] that convey a specific meaning. If this cannot be done without confusing the reader, then you need to explain what you mean within the context of how that word or phrase is used within a discipline.

IV. Language The investigation of research problems in the social sciences is often complex and multi- dimensional . Therefore, it is important that you use unambiguous language. Well-structured paragraphs and clear topic sentences enable a reader to follow your line of thinking without difficulty. Your language should be concise, formal, and express precisely what you want it to mean. Do not use vague expressions that are not specific or precise enough for the reader to derive exact meaning ["they," "we," "people," "the organization," etc.], abbreviations like 'i.e.' ["in other words"], 'e.g.' ["for example"], or 'a.k.a.' ["also known as"], and the use of unspecific determinate words ["super," "very," "incredible," "huge," etc.].

V. Punctuation Scholars rely on precise words and language to establish the narrative tone of their work and, therefore, punctuation marks are used very deliberately. For example, exclamation points are rarely used to express a heightened tone because it can come across as unsophisticated or over-excited. Dashes should be limited to the insertion of an explanatory comment in a sentence, while hyphens should be limited to connecting prefixes to words [e.g., multi-disciplinary] or when forming compound phrases [e.g., commander-in-chief]. Finally, understand that semi-colons represent a pause that is longer than a comma, but shorter than a period in a sentence. In general, there are four grammatical uses of semi-colons: when a second clause expands or explains the first clause; to describe a sequence of actions or different aspects of the same topic; placed before clauses which begin with "nevertheless", "therefore", "even so," and "for instance”; and, to mark off a series of phrases or clauses which contain commas. If you are not confident about when to use semi-colons [and most of the time, they are not required for proper punctuation], rewrite using shorter sentences or revise the paragraph.

VI. Academic Conventions Among the most important rules and principles of academic engagement of a writing is citing sources in the body of your paper and providing a list of references as either footnotes or endnotes. The academic convention of citing sources facilitates processes of intellectual discovery, critical thinking, and applying a deliberate method of navigating through the scholarly landscape by tracking how cited works are propagated by scholars over time . Aside from citing sources, other academic conventions to follow include the appropriate use of headings and subheadings, properly spelling out acronyms when first used in the text, avoiding slang or colloquial language, avoiding emotive language or unsupported declarative statements, avoiding contractions [e.g., isn't], and using first person and second person pronouns only when necessary.

VII. Evidence-Based Reasoning Assignments often ask you to express your own point of view about the research problem. However, what is valued in academic writing is that statements are based on evidence-based reasoning. This refers to possessing a clear understanding of the pertinent body of knowledge and academic debates that exist within, and often external to, your discipline concerning the topic. You need to support your arguments with evidence from scholarly [i.e., academic or peer-reviewed] sources. It should be an objective stance presented as a logical argument; the quality of the evidence you cite will determine the strength of your argument. The objective is to convince the reader of the validity of your thoughts through a well-documented, coherent, and logically structured piece of writing. This is particularly important when proposing solutions to problems or delineating recommended courses of action.

VIII. Thesis-Driven Academic writing is “thesis-driven,” meaning that the starting point is a particular perspective, idea, or position applied to the chosen topic of investigation, such as, establishing, proving, or disproving solutions to the questions applied to investigating the research problem. Note that a problem statement without the research questions does not qualify as academic writing because simply identifying the research problem does not establish for the reader how you will contribute to solving the problem, what aspects you believe are most critical, or suggest a method for gathering information or data to better understand the problem.

IX. Complexity and Higher-Order Thinking Academic writing addresses complex issues that require higher-order thinking skills applied to understanding the research problem [e.g., critical, reflective, logical, and creative thinking as opposed to, for example, descriptive or prescriptive thinking]. Higher-order thinking skills include cognitive processes that are used to comprehend, solve problems, and express concepts or that describe abstract ideas that cannot be easily acted out, pointed to, or shown with images. Think of your writing this way: One of the most important attributes of a good teacher is the ability to explain complexity in a way that is understandable and relatable to the topic being presented during class. This is also one of the main functions of academic writing--examining and explaining the significance of complex ideas as clearly as possible. As a writer, you must adopt the role of a good teacher by summarizing complex information into a well-organized synthesis of ideas, concepts, and recommendations that contribute to a better understanding of the research problem.

Academic Writing. Writing Center. Colorado Technical College; Hartley, James. Academic Writing and Publishing: A Practical Guide . New York: Routledge, 2008; Murray, Rowena and Sarah Moore. The Handbook of Academic Writing: A Fresh Approach . New York: Open University Press, 2006; Johnson, Roy. Improve Your Writing Skills . Manchester, UK: Clifton Press, 1995; Nygaard, Lynn P. Writing for Scholars: A Practical Guide to Making Sense and Being Heard . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2015; Silvia, Paul J. How to Write a Lot: A Practical Guide to Productive Academic Writing . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2007; Style, Diction, Tone, and Voice. Writing Center, Wheaton College; Sword, Helen. Stylish Academic Writing . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012.

Strategies for...

Understanding Academic Writing and Its Jargon

The very definition of research jargon is language specific to a particular community of practitioner-researchers . Therefore, in modern university life, jargon represents the specific language and meaning assigned to words and phrases specific to a discipline or area of study. For example, the idea of being rational may hold the same general meaning in both political science and psychology, but its application to understanding and explaining phenomena within the research domain of a each discipline may have subtle differences based upon how scholars in that discipline apply the concept to the theories and practice of their work.

Given this, it is important that specialist terminology [i.e., jargon] must be used accurately and applied under the appropriate conditions . Subject-specific dictionaries are the best places to confirm the meaning of terms within the context of a specific discipline. These can be found by either searching in the USC Libraries catalog by entering the disciplinary and the word dictionary [e.g., sociology and dictionary] or using a database such as Credo Reference [a curated collection of subject encyclopedias, dictionaries, handbooks, guides from highly regarded publishers] . It is appropriate for you to use specialist language within your field of study, but you should avoid using such language when writing for non-academic or general audiences.

Problems with Opaque Writing

A common criticism of scholars is that they can utilize needlessly complex syntax or overly expansive vocabulary that is impenetrable or not well-defined. When writing, avoid problems associated with opaque writing by keeping in mind the following:

1. Excessive use of specialized terminology . Yes, it is appropriate for you to use specialist language and a formal style of expression in academic writing, but it does not mean using "big words" just for the sake of doing so. Overuse of complex or obscure words or writing complicated sentence constructions gives readers the impression that your paper is more about style than substance; it leads the reader to question if you really know what you are talking about. Focus on creating clear, concise, and elegant prose that minimizes reliance on specialized terminology.

2. Inappropriate use of specialized terminology . Because you are dealing with concepts, research, and data within your discipline, you need to use the technical language appropriate to that area of study. However, nothing will undermine the validity of your study quicker than the inappropriate application of a term or concept. Avoid using terms whose meaning you are unsure of--do not just guess or assume! Consult the meaning of terms in specialized, discipline-specific dictionaries by searching the USC Libraries catalog or the Credo Reference database [see above].

Additional Problems to Avoid

In addition to understanding the use of specialized language, there are other aspects of academic writing in the social sciences that you should be aware of. These problems include:

- Personal nouns . Excessive use of personal nouns [e.g., I, me, you, us] may lead the reader to believe the study was overly subjective. These words can be interpreted as being used only to avoid presenting empirical evidence about the research problem. Limit the use of personal nouns to descriptions of things you actually did [e.g., "I interviewed ten teachers about classroom management techniques..."]. Note that personal nouns are generally found in the discussion section of a paper because this is where you as the author/researcher interpret and describe your work.

- Directives . Avoid directives that demand the reader to "do this" or "do that." Directives should be framed as evidence-based recommendations or goals leading to specific outcomes. Note that an exception to this can be found in various forms of action research that involve evidence-based advocacy for social justice or transformative change. Within this area of the social sciences, authors may offer directives for action in a declarative tone of urgency.

- Informal, conversational tone using slang and idioms . Academic writing relies on excellent grammar and precise word structure. Your narrative should not include regional dialects or slang terms because they can be open to interpretation. Your writing should be direct and concise using standard English.

- Wordiness. Focus on being concise, straightforward, and developing a narrative that does not have confusing language . By doing so, you help eliminate the possibility of the reader misinterpreting the design and purpose of your study.

- Vague expressions (e.g., "they," "we," "people," "the company," "that area," etc.). Being concise in your writing also includes avoiding vague references to persons, places, or things. While proofreading your paper, be sure to look for and edit any vague or imprecise statements that lack context or specificity.

- Numbered lists and bulleted items . The use of bulleted items or lists should be used only if the narrative dictates a need for clarity. For example, it is fine to state, "The four main problems with hedge funds are:" and then list them as 1, 2, 3, 4. However, in academic writing, this must then be followed by detailed explanation and analysis of each item. Given this, the question you should ask yourself while proofreading is: why begin with a list in the first place rather than just starting with systematic analysis of each item arranged in separate paragraphs? Also, be careful using numbers because they can imply a ranked order of priority or importance. If none exists, use bullets and avoid checkmarks or other symbols.

- Descriptive writing . Describing a research problem is an important means of contextualizing a study. In fact, some description or background information may be needed because you can not assume the reader knows the key aspects of the topic. However, the content of your paper should focus on methodology, the analysis and interpretation of findings, and their implications as they apply to the research problem rather than background information and descriptions of tangential issues.

- Personal experience. Drawing upon personal experience [e.g., traveling abroad; caring for someone with Alzheimer's disease] can be an effective way of introducing the research problem or engaging your readers in understanding its significance. Use personal experience only as an example, though, because academic writing relies on evidence-based research. To do otherwise is simply story-telling.

NOTE: Rules concerning excellent grammar and precise word structure do not apply when quoting someone. A quote should be inserted in the text of your paper exactly as it was stated. If the quote is especially vague or hard to understand, consider paraphrasing it or using a different quote to convey the same meaning. Consider inserting the term "sic" in brackets after the quoted text to indicate that the quotation has been transcribed exactly as found in the original source, but the source had grammar, spelling, or other errors. The adverb sic informs the reader that the errors are not yours.

Academic Writing. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Academic Writing Style. First-Year Seminar Handbook. Mercer University; Bem, Daryl J. Writing the Empirical Journal Article. Cornell University; College Writing. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Murray, Rowena and Sarah Moore. The Handbook of Academic Writing: A Fresh Approach . New York: Open University Press, 2006; Johnson, Eileen S. “Action Research.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education . Edited by George W. Noblit and Joseph R. Neikirk. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020); Oppenheimer, Daniel M. "Consequences of Erudite Vernacular Utilized Irrespective of Necessity: Problems with Using Long Words Needlessly." Applied Cognitive Psychology 20 (2006): 139-156; Ezza, El-Sadig Y. and Touria Drid. T eaching Academic Writing as a Discipline-Specific Skill in Higher Education . Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2020; Pernawan, Ari. Common Flaws in Students' Research Proposals. English Education Department. Yogyakarta State University; Style. College Writing. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Invention: Five Qualities of Good Writing. The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Sword, Helen. Stylish Academic Writing . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012; What Is an Academic Paper? Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Improving Academic Writing

To improve your academic writing skills, you should focus your efforts on three key areas: 1. Clear Writing . The act of thinking about precedes the process of writing about. Good writers spend sufficient time distilling information and reviewing major points from the literature they have reviewed before creating their work. Writing detailed outlines can help you clearly organize your thoughts. Effective academic writing begins with solid planning, so manage your time carefully. 2. Excellent Grammar . Needless to say, English grammar can be difficult and complex; even the best scholars take many years before they have a command of the major points of good grammar. Take the time to learn the major and minor points of good grammar. Spend time practicing writing and seek detailed feedback from professors. Take advantage of the Writing Center on campus if you need help. Proper punctuation and good proofreading skills can significantly improve academic writing [see sub-tab for proofreading you paper ].

Refer to these three basic resources to help your grammar and writing skills:

- A good writing reference book, such as, Strunk and White’s book, The Elements of Style or the St. Martin's Handbook ;

- A college-level dictionary, such as, Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary ;

- The latest edition of Roget's Thesaurus in Dictionary Form .

3. Consistent Stylistic Approach . Whether your professor expresses a preference to use MLA, APA or the Chicago Manual of Style or not, choose one style manual and stick to it. Each of these style manuals provide rules on how to write out numbers, references, citations, footnotes, and lists. Consistent adherence to a style of writing helps with the narrative flow of your paper and improves its readability. Note that some disciplines require a particular style [e.g., education uses APA] so as you write more papers within your major, your familiarity with it will improve.

II. Evaluating Quality of Writing

A useful approach for evaluating the quality of your academic writing is to consider the following issues from the perspective of the reader. While proofreading your final draft, critically assess the following elements in your writing.

- It is shaped around one clear research problem, and it explains what that problem is from the outset.

- Your paper tells the reader why the problem is important and why people should know about it.

- You have accurately and thoroughly informed the reader what has already been published about this problem or others related to it and noted important gaps in the research.

- You have provided evidence to support your argument that the reader finds convincing.

- The paper includes a description of how and why particular evidence was collected and analyzed, and why specific theoretical arguments or concepts were used.

- The paper is made up of paragraphs, each containing only one controlling idea.

- You indicate how each section of the paper addresses the research problem.

- You have considered counter-arguments or counter-examples where they are relevant.

- Arguments, evidence, and their significance have been presented in the conclusion.

- Limitations of your research have been explained as evidence of the potential need for further study.

- The narrative flows in a clear, accurate, and well-organized way.

Boscoloa, Pietro, Barbara Arféb, and Mara Quarisaa. “Improving the Quality of Students' Academic Writing: An Intervention Study.” Studies in Higher Education 32 (August 2007): 419-438; Academic Writing. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Academic Writing Style. First-Year Seminar Handbook. Mercer University; Bem, Daryl J. Writing the Empirical Journal Article. Cornell University; Candlin, Christopher. Academic Writing Step-By-Step: A Research-based Approach . Bristol, CT: Equinox Publishing Ltd., 2016; College Writing. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Style . College Writing. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Invention: Five Qualities of Good Writing. The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Sword, Helen. Stylish Academic Writing . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012; What Is an Academic Paper? Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College.

Writing Tip

Considering the Passive Voice in Academic Writing

In the English language, we are able to construct sentences in the following way: 1. "The policies of Congress caused the economic crisis." 2. "The economic crisis was caused by the policies of Congress."

The decision about which sentence to use is governed by whether you want to focus on “Congress” and what they did, or on “the economic crisis” and what caused it. This choice in focus is achieved with the use of either the active or the passive voice. When you want your readers to focus on the "doer" of an action, you can make the "doer"' the subject of the sentence and use the active form of the verb. When you want readers to focus on the person, place, or thing affected by the action, or the action itself, you can make the effect or the action the subject of the sentence by using the passive form of the verb.

Often in academic writing, scholars don't want to focus on who is doing an action, but on who is receiving or experiencing the consequences of that action. The passive voice is useful in academic writing because it allows writers to highlight the most important participants or events within sentences by placing them at the beginning of the sentence.

Use the passive voice when:

- You want to focus on the person, place, or thing affected by the action, or the action itself;

- It is not important who or what did the action;

- You want to be impersonal or more formal.

Form the passive voice by:

- Turning the object of the active sentence into the subject of the passive sentence.

- Changing the verb to a passive form by adding the appropriate form of the verb "to be" and the past participle of the main verb.

NOTE: Consult with your professor about using the passive voice before submitting your research paper. Some strongly discourage its use!

Active and Passive Voice. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Diefenbach, Paul. Future of Digital Media Syllabus. Drexel University; Passive Voice. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina.

- << Previous: 2. Preparing to Write

- Next: Applying Critical Thinking >>

- Last Updated: May 9, 2024 11:05 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Memberships

- Institutional Members

- Teacher Members

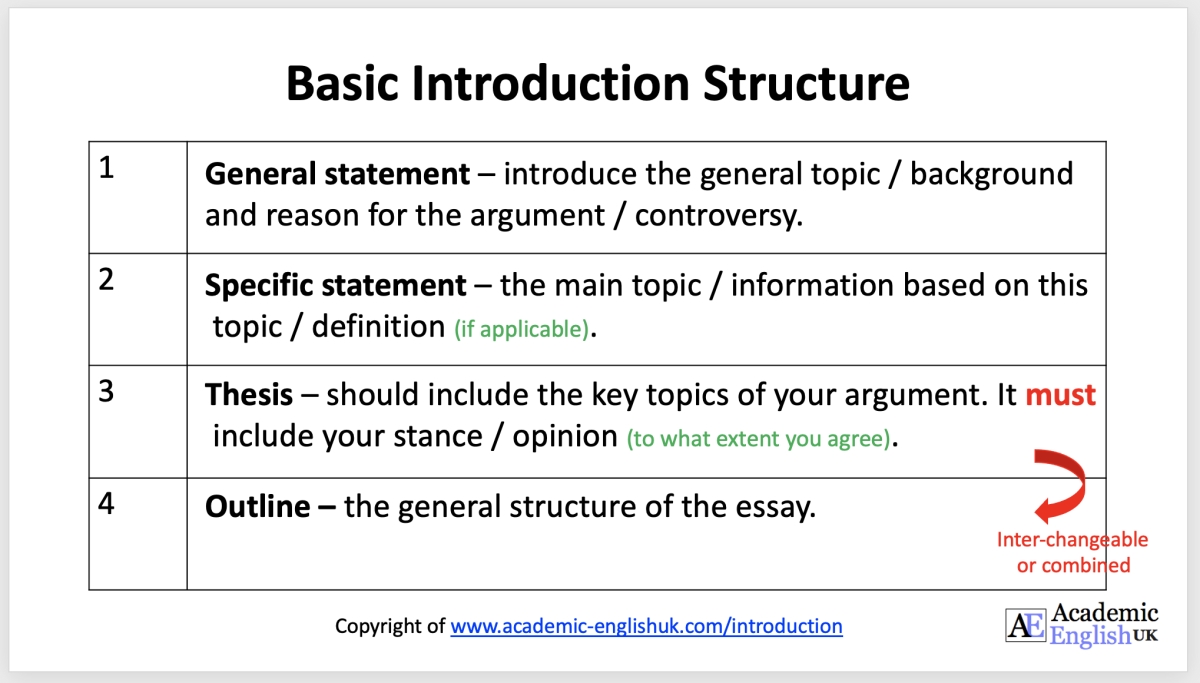

Thesis Statements

What is a thesis statement?

- A thesis is the main idea of your essay and includes your stance (opinion).

- A good thesis statement will direct the structure of your essay and will allow the reader to understand the ideas to be discussed within your paper.

- A thesis is usually stated in the opening paragraphs of a paper, most often in the last sentences of the introduction.

- Overall, a thesis should include the words from the essay question (if given one) , the key topics in the main body of the essay and your stance (opinion).

Thesis Statement Video

A short 7-minute video on what a thesis statement is and the key components of a thesis statement.

Thesis Statements: How to write a thesis statement

This lesson / worksheet presents the key sections to an academic introduction. It focuses on different writing structures using words like however, although, despite and then includes a writing task. Students write three thesis statements using the introduction models. Example Level: ** *** [B1/B2/C1] / TEACHER MEMBERSHIP / INSTITUTIONAL MEMBERSHIP

£4.00 – Add to cart Checkout Added to cart

Terms & Conditions of Use

An introduction structure with a thesis statement.

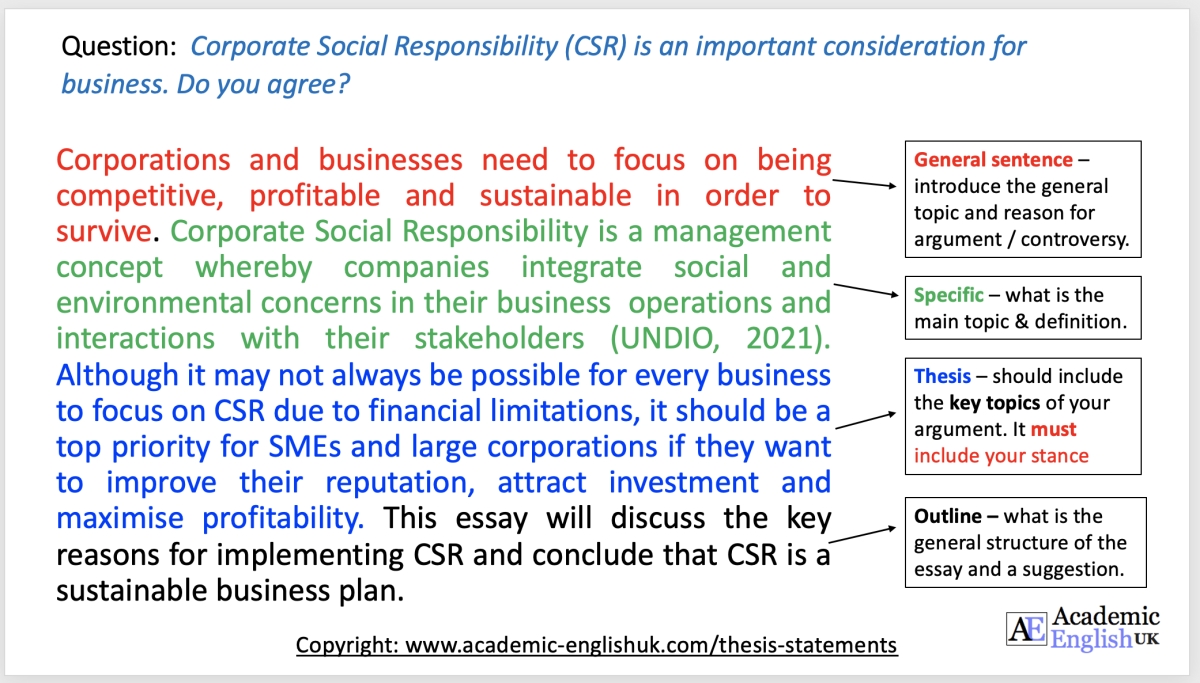

An introduction example on CSR

Thesis Statement Writing Structures

Notice the different structures and grammar

Thesis statement (Although): Although it may not always be possible for every business to focus on CSR due to financial limitations, it should be a top priority for SMEs andlarge corporations if they want to improve their reputation, attract investment and maximise profitability.

Thesis statement (However): It may not always be possible for every business to focus on CSR due to financial limitations. However, it should be a top priority for SMEs and large corporations if they want to improve their reputation, attract investment and maximise profitability.

Thesis statement (Despite) : Despite not always being possible for every business to focus on CSR due to financial limitations, it should be a top priority for SMEs and large corporations if they want to improve their reputation, attract investment and maximise profitability.

Thesis + outline combined

Thesis Statements: How to write a thesis statement

Introductions: How to write an academic introduction

This lesson / worksheet presents the key sections to an academic introduction. It then focuses on highlighting those key sections in three model introductions with particular attention to the thesis (question / topics / stance) and finally finishes with writing an introduction using a range of titles. Example Level: ** *** [B1/B2/C1] / Website link / TEACHER MEMBERSHIP / INSTITUTIONAL MEMBERSHIP

A Thesis Statement Generator

Click on the picture – this will take you to an online thesis statement generator – here

online resources

Medical English

New for 2024

DropBox Files

Members only

Instant Lessons

OneDrive Files

Topic-lessons

Feedback Forms

6-Week Course

SPSE Essays

Free Resources

Charts and graphs

AEUK The Blog

12-Week Course

Advertisement:.

Essay and dissertation writing skills

Planning your essay

Writing your introduction

Structuring your essay

- Writing essays in science subjects

- Brief video guides to support essay planning and writing

- Writing extended essays and dissertations

- Planning your dissertation writing time

Structuring your dissertation

- Top tips for writing longer pieces of work

Advice on planning and writing essays and dissertations

University essays differ from school essays in that they are less concerned with what you know and more concerned with how you construct an argument to answer the question. This means that the starting point for writing a strong essay is to first unpick the question and to then use this to plan your essay before you start putting pen to paper (or finger to keyboard).

A really good starting point for you are these short, downloadable Tips for Successful Essay Writing and Answering the Question resources. Both resources will help you to plan your essay, as well as giving you guidance on how to distinguish between different sorts of essay questions.

You may find it helpful to watch this seven-minute video on six tips for essay writing which outlines how to interpret essay questions, as well as giving advice on planning and structuring your writing:

Different disciplines will have different expectations for essay structure and you should always refer to your Faculty or Department student handbook or course Canvas site for more specific guidance.

However, broadly speaking, all essays share the following features:

Essays need an introduction to establish and focus the parameters of the discussion that will follow. You may find it helpful to divide the introduction into areas to demonstrate your breadth and engagement with the essay question. You might define specific terms in the introduction to show your engagement with the essay question; for example, ‘This is a large topic which has been variously discussed by many scientists and commentators. The principle tension is between the views of X and Y who define the main issues as…’ Breadth might be demonstrated by showing the range of viewpoints from which the essay question could be considered; for example, ‘A variety of factors including economic, social and political, influence A and B. This essay will focus on the social and economic aspects, with particular emphasis on…..’

Watch this two-minute video to learn more about how to plan and structure an introduction:

The main body of the essay should elaborate on the issues raised in the introduction and develop an argument(s) that answers the question. It should consist of a number of self-contained paragraphs each of which makes a specific point and provides some form of evidence to support the argument being made. Remember that a clear argument requires that each paragraph explicitly relates back to the essay question or the developing argument.

- Conclusion: An essay should end with a conclusion that reiterates the argument in light of the evidence you have provided; you shouldn’t use the conclusion to introduce new information.

- References: You need to include references to the materials you’ve used to write your essay. These might be in the form of footnotes, in-text citations, or a bibliography at the end. Different systems exist for citing references and different disciplines will use various approaches to citation. Ask your tutor which method(s) you should be using for your essay and also consult your Department or Faculty webpages for specific guidance in your discipline.

Essay writing in science subjects