How To Structure Your Literature Review

3 options to help structure your chapter.

By: Amy Rommelspacher (PhD) | Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | November 2020 (Updated May 2023)

Writing the literature review chapter can seem pretty daunting when you’re piecing together your dissertation or thesis. As we’ve discussed before , a good literature review needs to achieve a few very important objectives – it should:

- Demonstrate your knowledge of the research topic

- Identify the gaps in the literature and show how your research links to these

- Provide the foundation for your conceptual framework (if you have one)

- Inform your own methodology and research design

To achieve this, your literature review needs a well-thought-out structure . Get the structure of your literature review chapter wrong and you’ll struggle to achieve these objectives. Don’t worry though – in this post, we’ll look at how to structure your literature review for maximum impact (and marks!).

But wait – is this the right time?

Deciding on the structure of your literature review should come towards the end of the literature review process – after you have collected and digested the literature, but before you start writing the chapter.

In other words, you need to first develop a rich understanding of the literature before you even attempt to map out a structure. There’s no use trying to develop a structure before you’ve fully wrapped your head around the existing research.

Equally importantly, you need to have a structure in place before you start writing , or your literature review will most likely end up a rambling, disjointed mess.

Importantly, don’t feel that once you’ve defined a structure you can’t iterate on it. It’s perfectly natural to adjust as you engage in the writing process. As we’ve discussed before , writing is a way of developing your thinking, so it’s quite common for your thinking to change – and therefore, for your chapter structure to change – as you write.

Need a helping hand?

Like any other chapter in your thesis or dissertation, your literature review needs to have a clear, logical structure. At a minimum, it should have three essential components – an introduction , a body and a conclusion .

Let’s take a closer look at each of these.

1: The Introduction Section

Just like any good introduction, the introduction section of your literature review should introduce the purpose and layout (organisation) of the chapter. In other words, your introduction needs to give the reader a taste of what’s to come, and how you’re going to lay that out. Essentially, you should provide the reader with a high-level roadmap of your chapter to give them a taste of the journey that lies ahead.

Here’s an example of the layout visualised in a literature review introduction:

Your introduction should also outline your topic (including any tricky terminology or jargon) and provide an explanation of the scope of your literature review – in other words, what you will and won’t be covering (the delimitations ). This helps ringfence your review and achieve a clear focus . The clearer and narrower your focus, the deeper you can dive into the topic (which is typically where the magic lies).

Depending on the nature of your project, you could also present your stance or point of view at this stage. In other words, after grappling with the literature you’ll have an opinion about what the trends and concerns are in the field as well as what’s lacking. The introduction section can then present these ideas so that it is clear to examiners that you’re aware of how your research connects with existing knowledge .

2: The Body Section

The body of your literature review is the centre of your work. This is where you’ll present, analyse, evaluate and synthesise the existing research. In other words, this is where you’re going to earn (or lose) the most marks. Therefore, it’s important to carefully think about how you will organise your discussion to present it in a clear way.

The body of your literature review should do just as the description of this chapter suggests. It should “review” the literature – in other words, identify, analyse, and synthesise it. So, when thinking about structuring your literature review, you need to think about which structural approach will provide the best “review” for your specific type of research and objectives (we’ll get to this shortly).

There are (broadly speaking) three options for organising your literature review.

Option 1: Chronological (according to date)

Organising the literature chronologically is one of the simplest ways to structure your literature review. You start with what was published first and work your way through the literature until you reach the work published most recently. Pretty straightforward.

The benefit of this option is that it makes it easy to discuss the developments and debates in the field as they emerged over time. Organising your literature chronologically also allows you to highlight how specific articles or pieces of work might have changed the course of the field – in other words, which research has had the most impact . Therefore, this approach is very useful when your research is aimed at understanding how the topic has unfolded over time and is often used by scholars in the field of history. That said, this approach can be utilised by anyone that wants to explore change over time .

For example , if a student of politics is investigating how the understanding of democracy has evolved over time, they could use the chronological approach to provide a narrative that demonstrates how this understanding has changed through the ages.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself to help you structure your literature review chronologically.

- What is the earliest literature published relating to this topic?

- How has the field changed over time? Why?

- What are the most recent discoveries/theories?

In some ways, chronology plays a part whichever way you decide to structure your literature review, because you will always, to a certain extent, be analysing how the literature has developed. However, with the chronological approach, the emphasis is very firmly on how the discussion has evolved over time , as opposed to how all the literature links together (which we’ll discuss next ).

Option 2: Thematic (grouped by theme)

The thematic approach to structuring a literature review means organising your literature by theme or category – for example, by independent variables (i.e. factors that have an impact on a specific outcome).

As you’ve been collecting and synthesising literature , you’ll likely have started seeing some themes or patterns emerging. You can then use these themes or patterns as a structure for your body discussion. The thematic approach is the most common approach and is useful for structuring literature reviews in most fields.

For example, if you were researching which factors contributed towards people trusting an organisation, you might find themes such as consumers’ perceptions of an organisation’s competence, benevolence and integrity. Structuring your literature review thematically would mean structuring your literature review’s body section to discuss each of these themes, one section at a time.

Here are some questions to ask yourself when structuring your literature review by themes:

- Are there any patterns that have come to light in the literature?

- What are the central themes and categories used by the researchers?

- Do I have enough evidence of these themes?

PS – you can see an example of a thematically structured literature review in our literature review sample walkthrough video here.

Option 3: Methodological

The methodological option is a way of structuring your literature review by the research methodologies used . In other words, organising your discussion based on the angle from which each piece of research was approached – for example, qualitative , quantitative or mixed methodologies.

Structuring your literature review by methodology can be useful if you are drawing research from a variety of disciplines and are critiquing different methodologies. The point of this approach is to question how existing research has been conducted, as opposed to what the conclusions and/or findings the research were.

For example, a sociologist might centre their research around critiquing specific fieldwork practices. Their literature review will then be a summary of the fieldwork methodologies used by different studies.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself when structuring your literature review according to methodology:

- Which methodologies have been utilised in this field?

- Which methodology is the most popular (and why)?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the various methodologies?

- How can the existing methodologies inform my own methodology?

3: The Conclusion Section

Once you’ve completed the body section of your literature review using one of the structural approaches we discussed above, you’ll need to “wrap up” your literature review and pull all the pieces together to set the direction for the rest of your dissertation or thesis.

The conclusion is where you’ll present the key findings of your literature review. In this section, you should emphasise the research that is especially important to your research questions and highlight the gaps that exist in the literature. Based on this, you need to make it clear what you will add to the literature – in other words, justify your own research by showing how it will help fill one or more of the gaps you just identified.

Last but not least, if it’s your intention to develop a conceptual framework for your dissertation or thesis, the conclusion section is a good place to present this.

Example: Thematically Structured Review

In the video below, we unpack a literature review chapter so that you can see an example of a thematically structure review in practice.

Let’s Recap

In this article, we’ve discussed how to structure your literature review for maximum impact. Here’s a quick recap of what you need to keep in mind when deciding on your literature review structure:

- Just like other chapters, your literature review needs a clear introduction , body and conclusion .

- The introduction section should provide an overview of what you will discuss in your literature review.

- The body section of your literature review can be organised by chronology , theme or methodology . The right structural approach depends on what you’re trying to achieve with your research.

- The conclusion section should draw together the key findings of your literature review and link them to your research questions.

If you’re ready to get started, be sure to download our free literature review template to fast-track your chapter outline.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

27 Comments

Great work. This is exactly what I was looking for and helps a lot together with your previous post on literature review. One last thing is missing: a link to a great literature chapter of an journal article (maybe with comments of the different sections in this review chapter). Do you know any great literature review chapters?

I agree with you Marin… A great piece

I agree with Marin. This would be quite helpful if you annotate a nicely structured literature from previously published research articles.

Awesome article for my research.

I thank you immensely for this wonderful guide

It is indeed thought and supportive work for the futurist researcher and students

Very educative and good time to get guide. Thank you

Great work, very insightful. Thank you.

Thanks for this wonderful presentation. My question is that do I put all the variables into a single conceptual framework or each hypothesis will have it own conceptual framework?

Thank you very much, very helpful

This is very educative and precise . Thank you very much for dropping this kind of write up .

Pheeww, so damn helpful, thank you for this informative piece.

I’m doing a research project topic ; stool analysis for parasitic worm (enteric) worm, how do I structure it, thanks.

comprehensive explanation. Help us by pasting the URL of some good “literature review” for better understanding.

great piece. thanks for the awesome explanation. it is really worth sharing. I have a little question, if anyone can help me out, which of the options in the body of literature can be best fit if you are writing an architectural thesis that deals with design?

I am doing a research on nanofluids how can l structure it?

Beautifully clear.nThank you!

Lucid! Thankyou!

Brilliant work, well understood, many thanks

I like how this was so clear with simple language 😊😊 thank you so much 😊 for these information 😊

Insightful. I was struggling to come up with a sensible literature review but this has been really helpful. Thank you!

You have given thought-provoking information about the review of the literature.

Thank you. It has made my own research better and to impart your work to students I teach

I learnt a lot from this teaching. It’s a great piece.

I am doing research on EFL teacher motivation for his/her job. How Can I structure it? Is there any detailed template, additional to this?

You are so cool! I do not think I’ve read through something like this before. So nice to find somebody with some genuine thoughts on this issue. Seriously.. thank you for starting this up. This site is one thing that is required on the internet, someone with a little originality!

I’m asked to do conceptual, theoretical and empirical literature, and i just don’t know how to structure it

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Apr 15, 2021

7 Secrets to Write a PhD Literature Review The Right Way

Updated: Sep 27, 2021

A literature review gives your readers an idea about your scholarly understanding of the previous work in your research domain. It requires you to justify your work and demonstrate the importance of your research work with respect to the current state of knowledge. It is a great opportunity for you to examine the previous work and fill any gaps in it which may help you to make it a foundation for your own research.

The role of a literature review and its importance in your thesis can also be seen from here:

Role of a Literature Review|Walden University

Writing a literature review requires gathering loads of information by reading many articles, books, and papers related to your Ph.D. topic. And once you are done with the initial stage, you have to organize the important data collected and discuss it according to your learning. Now, all of this seems quite tedious.

You may have seen many people ranting when they have to write a literature review, and it is totally fine. But, does it help in writing a review? Obviously, no. You have to make this process interesting for yourself to remain focused.

Here are some secrets which can help you to enjoy writing an amazing literature review.

1. Make a Well-Structured Outline:

A literature review is exhaustive research on the topic under investigation so that you can become an expert on that topic. Therefore, it is important for you to make a well-structured outline before you start writing otherwise you won’t understand where to end as you’ll be having a lot of information. For example, a literature review must include an introduction and conclusion section, you should avoid direct quotations and use paraphrasing instead. Your literature review should be organized according to the theme and should be divided into various headings to shift from one topic to another. You can use comparative terms to agree or disagree with the author and provide your own opinion.

Check out this literature review template to have a more clear understanding of creating a well-structured outline for your literature review: Literature Review Template|Thompson Rivers University

2. Use Synthesis Matrix:

When you are gathering information from a lot of resources, and you have to ultimately gather them in one place then using a synthesis matrix could be very helpful for this purpose. A synthesis matrix is an outline that permits a researcher to sort and arrange the various contentions introduced on an issue. Across the highest point of the chart are the spaces to record sources, and at the edge of the chart are the spaces to record the primary concerns of contention on the current theme.

You can outline your whole literature review and keep a check and balance of which things you have covered and what is left. It simplifies your work greatly and helps in writing a literature review in a very organized manner.

See more on the use of synthesis matrix at Literature Review using synthesis Matrix and Synthesizing various sources

3. Change Your Perspective:

Another important thing that you must do before you start writing a literature review is to change your writing perspective. You don’t have to take it as a burden that Why am I even doing this? Yes, we know it is quite a dull task, but why not enjoy it if you have to do it after all?

Write it for yourself. Question yourself from time to time. Like what information would you like to extract from it while you are reading this review? Would it sound interesting to your self? Would you remain focused while reading this writing style? Will you love this review as a third person? Will this be an interesting thing to read?

When you become your critique you have high chances of improvement. You start writing a review such that you would like to read it yourself, and gradually you can write one interesting literature review for your thesis.

4. Read and Write Simultaneously:

A common mistake that many people make while writing a literature review is that they do all the readings and information gathering first and leave the writing at last. What happens is that they utilize all their energy and focus in the reading phase and when it's time to start the actual writing they feel exhausted and over-worked. Moreover, when they see a blank page in front of them after reading piles of paperwork they get demotivated and feel anxious that how they will manage to write such a long review.

How to avoid this anxiety?

One simple way is to start writing parallel to reading. When you are reading an article or paper, make notes of it or short bullet points. It will help you to keep a track of both what you have read and what you need to add to your literature review. And when you finally start compiling the review you will have your guideline instead of a blank paper which makes it quite easy for you to jot it all down on a paper.

5. Make a Proper Timeline and Stick To It:

Making a proper timeline to write a literature review is crucial. You don’t want to get stuck in it and end up completing your review in a year instead of weeks. To avoid this, take a day or two off, search through the internet or other resources that what helping material you would require reading, and then make a proper timeline of completing them and making notes simultaneously.

It will help you a lot to stay on track.

Here is a sample timeline you could follow: Research Sample Timeline

6. Go Easy On Yourself:

Yes, you heard it. Don’t be so harsh on yourself. Keep days off in your schedule and relax fully on those days. You don’t have to keep reading and writing 24/7, all days a week. Our mind needs to be relaxed on and off to remain functional. If you over-burden yourself you will eventually end up doing absolutely nothing because of over-work.

If you get stuck somewhere, seek help from your supervisor, friends or other resources, Don’t let your shyness or shame keep you away from achieving your target. We are all humans, and we do need help at some point in our lives so don’t discourage yourself to do so.

7. Interpret Your Understanding Comprehensively:

When writing a review you need to portray what you have truly learned from the already published work of other scholars. What many people do is they start cramming information to write a review and end up writing only a summary of that data, They don’t learn and understand anything from it. They just take it as a formality that has to be fulfilled. That is wrong.

You need to have clear concepts and must be able to demonstrate to others what you learned from the previous work and how your work would contribute towards it. This is the true essence of writing a literature review, and it will benefit you the most for your research process.

If you are having any difficulty in writing or editing your thesis Literature Review you can visit our website to seek help and guidance by the following link:

Scholars Doctoral Editing and Consulting

Scholars Professional Editing Group LLC :

Website: https://www.thescholarsediting.com/

Email Us: [email protected]

Contact Us: (302) 295-4953

CLICK HERE TO BOOK A FREE CONSULTATION NOW: Scholars Consultation

Recent Posts

Structuring Your Literature Review: Visualizing Key Themes and Sub-themes

Beginning Your Literature Review: Essential Techniques and Strategies

5 Reasons Why You Should Use NVivo For Your PhD Research

- What Is a PhD Literature Review?

- Doing a PhD

A literature review is a critical analysis of published academic literature, mainly peer-reviewed papers and books, on a specific topic. This isn’t just a list of published studies but is a document summarising and critically appraising the main work by researchers in the field, the key findings, limitations and gaps identified in the knowledge.

- The aim of a literature review is to critically assess the literature in your chosen field of research and be able to present an overview of the current knowledge gained from previous work.

- By the conclusion of your literature review, you as a researcher should have identified the gaps in knowledge in your field; i.e. the unanswered research questions which your PhD project will help to answer.

- Quality not quantity is the approach to use when writing a literature review for a PhD but as a general rule of thumb, most are between 6,000 and 12,000 words.

What Is the Purpose of a Literature Review?

First, to be clear on what a PhD literature review is NOT: it is not a ‘paper by paper’ summary of what others have done in your field. All you’re doing here is listing out all the papers and book chapters you’ve found with some text joining things together. This is a common mistake made by PhD students early on in their research project. This is a sign of poor academic writing and if it’s not picked up by your supervisor, it’ll definitely be by your examiners.

The biggest issue your examiners will have here is that you won’t have demonstrated an application of critical thinking when examining existing knowledge from previous research. This is an important part of the research process as a PhD student. It’s needed to show where the gaps in knowledge were, and how then you were able to identify the novelty of each research question and subsequent work.

The five main outcomes from carrying out a good literature review should be:

- An understanding of what has been published in your subject area of research,

- An appreciation of the leading research groups and authors in your field and their key contributions to the research topic,

- Knowledge of the key theories in your field,

- Knowledge of the main research areas within your field of interest,

- A clear understanding of the research gap in knowledge that will help to motivate your PhD research questions .

When assessing the academic papers or books that you’ve come across, you must think about the strengths and weaknesses of them; what was novel about their work and what were the limitations? Are different sources of relevant literature coming to similar conclusions and complementing each other, or are you seeing different outcomes on the same topic by different researchers?

When Should I Write My Literature Review?

In the structure of your PhD thesis , your literature review is effectively your first main chapter. It’s at the start of your thesis and should, therefore, be a task you perform at the start of your research. After all, you need to have reviewed the literature to work out how your research can contribute novel findings to your area of research. Sometimes, however, in particular when you apply for a PhD project with a pre-defined research title and research questions, your supervisor may already know where the gaps in knowledge are.

You may be tempted to skip the literature review and dive straight into tackling the set questions (then completing the review at the end before thesis submission) but we strongly advise against this. Whilst your supervisor will be very familiar with the area, you as a doctoral student will not be and so it is essential that you gain this understanding before getting into the research.

How Long Should the Literature Review Be?

As your literature review will be one of your main thesis chapters, it needs to be a substantial body of work. It’s not a good strategy to have a thesis writing process here based on a specific word count, but know that most reviews are typically between 6,000 and 12,000 words. The length will depend on how much relevant material has previously been published in your field.

A point to remember though is that the review needs to be easy to read and avoid being filled with unnecessary information; in your search of selected literature, consider filtering out publications that don’t appear to add anything novel to the discussion – this might be useful in fields with hundreds of papers.

How Do I Write the Literature Review?

Before you start writing your literature review, you need to be clear on the topic you are researching.

1. Evaluating and Selecting the Publications

After completing your literature search and downloading all the papers you find, you may find that you have a lot of papers to read through ! You may find that you have so many papers that it’s unreasonable to read through all of them in their entirety, so you need to find a way to understand what they’re about and decide if they’re important quickly.

A good starting point is to read the abstract of the paper to gauge if it is useful and, as you do so, consider the following questions in your mind:

- What was the overarching aim of the paper?

- What was the methodology used by the authors?

- Was this an experimental study or was this more theoretical in its approach?

- What were the results and what did the authors conclude in their paper?

- How does the data presented in this paper relate to other publications within this field?

- Does it add new knowledge, does it raise more questions or does it confirm what is already known in your field? What is the key concept that the study described?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of this study, and in particular, what are the limitations?

2. Identifying Themes

To put together the structure of your literature review you need to identify the common themes that emerge from the collective papers and books that you have read. Key things to think about are:

- Are there common methodologies different authors have used or have these changed over time?

- Do the research questions change over time or are the key question’s still unanswered?

- Is there general agreement between different research groups in the main results and outcomes, or do different authors provide differing points of view and different conclusions?

- What are the key papers in your field that have had the biggest impact on the research?

- Have different publications identified similar weaknesses or limitations or gaps in the knowledge that still need to be addressed?

Structuring and Writing Your Literature Review

There are several ways in which you can structure a literature review and this may depend on if, for example, your project is a science or non-science based PhD.

One approach may be to tell a story about how your research area has developed over time. You need to be careful here that you don’t just describe the different papers published in chronological order but that you discuss how different studies have motivated subsequent studies, how the knowledge has developed over time in your field, concluding with what is currently known, and what is currently not understood.

Alternatively, you may find from reading your papers that common themes emerge and it may be easier to develop your review around these, i.e. a thematic review. For example, if you are writing up about bridge design, you may structure the review around the themes of regulation, analysis, and sustainability.

As another approach, you might want to talk about the different research methodologies that have been used. You could then compare and contrast the results and ultimate conclusions that have been drawn from each.

As with all your chapters in your thesis, your literature review will be broken up into three key headings, with the basic structure being the introduction, the main body and conclusion. Within the main body, you will use several subheadings to separate out the topics depending on if you’re structuring it by the time period, the methods used or the common themes that have emerged.

The important thing to think about as you write your main body of text is to summarise the key takeaway messages from each research paper and how they come together to give one or more conclusions. Don’t just stop at summarising the papers though, instead continue on to give your analysis and your opinion on how these previous publications fit into the wider research field and where they have an impact. Emphasise the strengths of the studies you have evaluated also be clear on the limitations of previous work how these may have influenced the results and conclusions of the studies.

In your concluding paragraphs focus your discussion on how your critical evaluation of literature has helped you identify unanswered research questions and how you plan to address these in your PhD project. State the research problem you’re going to address and end with the overarching aim and key objectives of your work .

When writing at a graduate level, you have to take a critical approach when reading existing literature in your field to determine if and how it added value to existing knowledge. You may find that a large number of the papers on your reference list have the right academic context but are essentially saying the same thing. As a graduate student, you’ll need to take a methodological approach to work through this existing research to identify what is relevant literature and what is not.

You then need to go one step further to interpret and articulate the current state of what is known, based on existing theories, and where the research gaps are. It is these gaps in the literature that you will address in your own research project.

- Decide on a research area and an associated research question.

- Decide on the extent of your scope and start looking for literature.

- Review and evaluate the literature.

- Plan an outline for your literature review and start writing it.

Browse PhDs Now

Join thousands of students.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Do you really want to publish your literature review? Advice for PhD students

Why publishing your literature review as your first paper may not be a good idea

Tatiana Andreeva - Sun 20 Jun 2021 08:20 (updated Wed 30 Aug 2023 10:03)

[Guest post by CYGNA member Tatiana Andreeva ]

Almost every PhD student I met had an idea that the literature review paper would be the first academic paper they publish. They thought of it being the first paper for two reasons - naturally literature review was the first stage of their PhD journey, but also they thought it was something relatively straightforward to do. To reinforce these ideas, in some PhD programmes I know publication of the literature review is routinely put as a milestone in the PhD progression plans.

At the same time, if you talk to academics who actually tried to publish a literature review, you would most often hear that it is a very challenging thing to do. Moreover, I recently realized that we rarely teach our graduate students how to do a literature review , let alone how to publish it . A weird mismatch, isn’t it? So, dear PhD students, I’d like to put some clarity around it for you. There are two key reasons why publishing literature review as your first paper may not be a good idea.

Not all literature reviews are made equal

First, the literature review you do as a first step of your PhD journey and publishable literature review are two different beasts: they have a different purpose, focus and audience.

The literature review you do as a first step of your PhD aims to inform you as a novice about existing literature and to help you identify an interesting research question or situate it better in the existing research landscape. You are likely to read different literatures and/or focus on different aspects, as you are trying to find your own research voice and space. As your PhD progresses and you get new ideas or unexpected empirical findings, you are likely to review the literature again (and again…)

Even if you do this literature review(s) following the best standards , it is very likely that parts of it will never be published – neither as a separate article, nor even as a literature review section of an empirical paper. Not because they are bad, but because they may end up being not so relevant for the final focus of your PhD. I know it is heartbreaking to discard pieces of work, especially our own writing, but if you think of them as steppingstones rather than final products, it becomes easier.

In contrast, the literature review that is done for publication aims to inform others - many of whom are likely to be experts in the field - about something beyond existing literature and to propose future research agenda for them (and maybe for you as well, but it is not the main goal). Therefore, it needs a clear and single focus - on a specific research problem within a specific body of literature. And, if all goes well, it should be published – at least, that is the plan.

The table below briefly summarizes these ideas:

Easy publication of literature reviews is a myth

Another reason why I think that planning to publish a literature review as a first paper in the suite of PhD publications is not a good idea is: the notion that such papers are easy to publish is a myth! I think it is actually even more difficult to publish a literature review than an empirical paper.

In an empirical paper, you always have an element of uniqueness, which is your empirical data. Indeed, nobody has collected something like this so it is unique. Sometimes when your data is interesting, it could happen that reviewers come back to you and say: " you need to improve your theory and develop a much stronger positioning of the paper, but your data itself is very interesting, so we give you a chance for R&R ".

In my experience, this would never happen with a literature review paper – because your data is not unique, it is something that has been already written and published. Everybody, if they want, can access it. So with the literature reviews is really becomes critical that from the very start you have a very clear and strong idea of what is the problem that hasn’t been solved that your literature review solves, and what would be your theoretical contribution. This is a challenging task for everyone, not only for a PhD student, so it might be too risky to start from it your publication journey.

All that said, it does not mean that you cannot - or should not - do a literature review publication. Indeed, at some point it may stem from the literature review you did for your PhD. I hope that understanding the differences between these beasts may help you to master both – and plan your PhD publication portfolio better.

Related blogposts

- Resources on doing a literature review

- Want to publish a literature review? Think of it as an empirical paper

- How to keep up-to-date with the literature, but avoid information overload?

- Is a literature review publication a low-cost project?

- Using Publish or Perish to do a literature review

- How to conduct a longitudinal literature review?

- New: Publish or Perish now also exports abstracts

- A framework for your literature review article: where to find one?

Find the resources on my website useful?

I cover all the expenses of operating my website privately. If you enjoyed this post and want to support me in maintaining my website, consider buying a copy of one of my books (see below) or supporting the Publish or Perish software .

Copyright © 2023 Tatiana Andreeva . All rights reserved. Page last modified on Wed 30 Aug 2023 10:03

Tatiana Andreeva's profile and contact details >>

The Literature Review: A Guide for Postgraduate Students

This guide provides postgraduate students with an overview of the literature review required for most research degrees. It will advise you on the common types of literature reviews across disciplines and will outline how the purpose and structure of each may differ slightly. Various approaches to effective content organisation and writing style are offered, along with some common strategies for effective writing and avoiding some common mistakes. This guide focuses mainly on the required elements of a standalone literature review, but the suggestions and advice apply to literature reviews incorporated into other chapters.

Please see the companion article ‘ The Literature Review: A Guide for Undergraduate Students ’ for an introduction to the basic elements of a literature review. This article focuses on aspects that are particular to postgraduate literature reviews, containing detailed advice and effective strategies for writing a successful literature review. It will address the following topics:

- The purpose of a literature review

- The structure of your literature review

- Strategies for writing an effective literature review

- Mistakes to avoid

The Purpose of a Literature Review

After developing your research proposal and writing a research statement, your literature review is one of the most important early tasks you will undertake for your postgraduate research degree. Many faculties and departments require postgraduate research students to write an initial literature review as part of their research proposal, which forms part of the candidature confirmation process that occurs six months into the research degree for full-time students (12 months for part-time students).

For example, a postgraduate student in history would normally write a 10,000-word research proposal—including a literature review—in the first six months of their PhD. This would be assessed in order to confirm the ongoing candidature of the student.

The literature review is your opportunity you show your supervisor (and ultimately, your examiners) that you understand the most important debates in your field, can identify the texts and authors most relevant to your particular topic, and can examine and evaluate these debates and texts both critically and in depth. You will be expected to provide a comprehensive, detailed and relevant range of scholarly works in your literature review.

In general, a literature review has a specific and directed purpose: to focus the reader’s attention on the significance and necessity of your research. By identifying a ‘gap’ in the current scholarship, you convince your readers that your own research is vital.

As the author, you will achieve these objectives by displaying your in-depth knowledge and understanding of the relevant scholarship in your field, situating your own research within this wider body of work , while critically analysing the scholarship and highlighting your own arguments in relation to that scholarship.

A well-focused, well-developed and well-researched literature review operates as a linchpin for your thesis, provides the background to your research and demonstrates your proficiency in some requisite academic skills.

The Structure of Your Literature Review

Postgraduate degrees can be made up of a long thesis (Master’s and PhD by research) or a shorter thesis and coursework (Master’s by coursework; although some Australian universities now require PhD students to undertake coursework in the first year of their degree). Some disciplines involve creative work (such as a novel or artwork) and an exegesis (such as a creative writing research or fine arts degree). Others can comprise a series of published works in the form of a ‘thesis by publication’ (most common in the science and medical fields).

The structure of a literature review will thus vary according to the discipline and the type of thesis. Some of the most common discipline-based variations are outlined in the following paragraphs.

Humanities and Social Science Degrees

Many humanities and social science theses will include a standalone literature review chapter after the introduction and before any methodology (or theoretical approaches) chapters. In these theses, the literature review might make up around 15 to 30 per cent of the total thesis length, reflecting its purpose as a supporting chapter.

Here, the literature review chapter will have an introduction, an appropriate number of discussion paragraphs and a conclusion. As with a research essay, the introduction operates as a ‘road map’ to the chapter. The introduction should outline and clarify the argument you are making in your thesis (Australian National University 2017), as readers will then have a context for the discussion and critical analysis paragraphs that follow.

The main discussion section can be divided further with subheadings, and the material organised in several possible ways: chronologically, thematically or from the better- to the lesser-known issues and arguments. The conclusion should provide a summary of the chapter overall, and should re-state your thesis statement, linking this to the gap you have identified in the literature that confirms the necessity of your research.

For some humanities’ disciplines, such as literature or history (Premaratne 2013, 236–54), where primary sources are central, the literature review may be conducted chapter-by-chapter, with each chapter focusing on one theme and set of scholarly secondary sources relevant to the primary source material.

Science and Mathematics Degrees

For some science or mathematics research degrees, the literature review may be part of the introduction. The relevant literature here may be limited in number and scope, and if the research project is experiment-based, rather than theoretically based, a lengthy critical analysis of past research may be unnecessary (beyond establishing its weaknesses or failings and thus the necessity for the current research). The literature review section will normally appear after the paragraphs that outline the study’s research question, main findings and theoretical framework. Other science-based degrees may follow the standalone literature review chapter more common in the social sciences.

Strategies for Writing an Effective Literature Review

A research thesis—whether for a Master’s degree or Doctor of Philosophy—is a long project, and the literature review, usually written early on, will most likely be reviewed and refined over the life of the thesis. This section will detail some useful strategies to ensure you write a successful literature review that meets the expectations of your supervisor and examiners.

Using a Mind Map

Before planning or writing, it can be beneficial to undertake a brainstorm exercise to initiate ideas, especially in relation to the organisation of your literature review. A mind map is a very effective technique that can get your ideas flowing prior to a more formal planning process.

A mind map is best created in landscape orientation. Begin by writing a very brief version of your research topic in the middle of the page and then expanding this with themes and sub-themes, identified by keywords or phrases and linked by associations or oppositions. The University of Adelaide provides an excellent introduction to mind mapping.

Planning is as essential at the chapter level as it is for your thesis overall. If you have begun work on your literature review with a mind map or similar process, you can use the themes or organisational categories that emerged to begin organising your content. Plan your literature review as if it were a research essay with an introduction, main body and conclusion.

Create a detailed outline for each main paragraph or section and list the works you will discuss and analyse, along with keywords to identify important themes, arguments and relevant data. By creating a ‘planning document’ in this way, you can keep track of your ideas and refine the plan as you go.

Maintaining a Current Reference List or Annotated Bibliography

It is vital that you maintain detailed and up-to-date records of all scholarly works that you read in relation to your thesis. You will need to ensure that you remain aware of current and developing research, theoretical debates and data as your degree progresses; and review and update the literature review as you work through your own research and writing.

To do this most effectively and efficiently, you will need to record precisely the bibliographic details of each source you use. Decide on the referencing style you will be using at an early stage (this is often dictated by your department or discipline, or suggested by your supervisor). If you begin to construct your reference list as you write your thesis, ensure that you follow any formatting and stylistic requirements for your chosen referencing style from the start (nothing is more onerous than undertaking this task as you are finishing your research degree).

Insert references (also known as ‘citations’) into the text or footnote section as you write your literature review, and be aware of all instances where you need to use a reference . The literature review chapter or section may appear to be overwhelmed with references, but this is just a reflection of the source-based content and purpose.

The Drawbacks of Referencing Software

We don’t recommend the use of referencing software to help you with your references because using this software almost always leads to errors and inconsistencies. They simply can’t be trusted to produce references that will be complete and accurate, properly following your particular referencing style to the letter.

Further, relying on software to create your references for you usually means that you won’t learn how to reference correctly yourself, which is an absolutely vital skill, especially if you are hoping to continue in academia.

Writing Style

Similar to structural matters, your writing style will depend to some extent on your discipline and the expectations and advice of your supervisors. Humanities- and creative arts–based disciplines may be more open to a wider variety of authorial voices. Even if this is so, it remains preferable to establish an academic voice that is credible, engaging and clear.

Simple stylistic strategies such as using the active—instead of the passive—voice, providing variety in sentence structure and length and preferring (where appropriate) simple language over convoluted or overly obscure words can help to ensure your academic writing is both formal and highly readable.

Reviewing, Rewriting and Editing

Although an initial draft is essential (and in some departments it is a formal requirement) to establish the ground for your own research and its place within the wider body of scholarship, the literature review will evolve, develop and be modified as you continue to research, write, review and rewrite your thesis. It is likely that your literature review will not be completed until you have almost finished the thesis itself, and a final assessment and edit of this section is essential to ensure you have included the most important scholarship that is relevant and necessary to your research.

It has happened to many students that a crucial piece of literature is published just as they are about to finalise their thesis, and they must revise their literature review in light of it. Unfortunately, this cannot be avoided, lest your examiners think that you are not aware of this key piece of scholarship. You need to ensure your final literature review reflects how your research now fits into the new landscape in your field after any recent developments.

Mistakes to Avoid

Some common mistakes can result in an ineffective literature review that could then flow on to the rest of your thesis. These mistakes include:

- Trying to read and include everything you find on your topic. The literature review should be selective as well as comprehensive, examining only those sources relevant to your research topic.

- Listing the scholarship as if you are writing an annotated bibliography or a series of summaries. Your discussion of the literature should be synthesised and holistic, and should have a logical progression that is appropriate to the organisation of your content.

- Failing to integrate your examination of the literature with your own thesis topic. You need to develop your discussion of each piece of scholarship in relation to other pieces of research, contextualising your analyses and conclusions in relation to your thesis statement or research topic and focusing on how your own research relates to, complements and extends the existing scholarship.

Writing the literature review is often the first task of your research degree. It is a focused reading and research activity that situates your own research in the wider scholarship, establishing yourself as an active member of the academic community through dialogue and debate. By reading, analysing and synthesising the existing scholarship on your topic, you gain a comprehensive and in-depth understanding, ensuring a solid basis for your own arguments and contributions. If you need advice on referencing , academic writing , time management or other aspects of your degree, you may find Capstone Editing’s other resources and blog articles useful.

Australian National University. 2017. ‘Literature Reviews’. Last accessed 28 March. http://www.anu.edu.au/students/learning-development/research-writing/literature-reviews.

Premaratne, Dhilara Darshana. 2013. ‘Discipline Based Variations in the Literature Review in the PhD Thesis: A Perspective from the Discipline of History’. Education and Research Perspectives 40: 236–54.

Other guides you may be interested in

Essay writing: everything you need to know and nothing you don’t—part 1: how to begin.

This guide will explain everything you need to know about how to organise, research and write an argumentative essay.

Essay Writing Part 2: How to Organise Your Research

Organising your research effectively is a crucial and often overlooked step to successful essay writing.

Located in northeastern New South Wales 200 kilometres south of Brisbane, Lismore offers students a good study–play balance, in a gorgeous sub-tropical climate.

Rockhampton

The administrative hub for Central Queensland, Rockhampton is a popular tourist attraction due to its many national parks and proximity to Great Keppel Island.

- Latest Posts

- Undergraduate Bloggers

- Graduate Bloggers

- Study Abroad Bloggers

- Guest Bloggers

- Browse Posts

- Browse Categories

Grant Golub

June 3rd, 2020, reflections on the first year of my phd.

Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

It is hard to believe the first year of my PhD programme is almost complete. It feels like just yesterday I was arriving in London to begin my degree. Adding to the surreal nature of the moment is the fact we have been under lockdown since March due to COVID-19. Since I am close to submitting my upgrade materials for my first year, I thought this would be a good time to reflect on my first year of the PhD at LSE.

As I’ve written in an earlier post, LSE is an ideal place to do a PhD because of its location in London, its world-class professors, and its proximity to countless archives and libraries . This has made it much easier to conduct research and prepare my dissertation as opposed to if I was at another university. I’ve been very privileged to have a wonderful supervisor who cares a lot about me and my work . Our conversations about my research have always been fruitful and give me new things to consider for the direction of my research. I have been very lucky to have such a hands-on supervisor.

One aspect of the PhD that I think many underestimate is how much work you actually do on your own . At LSE, like many British universities, there are one or two seminars you participate in to introduce skills you need for the PhD, but otherwise, you spend the bulk of your time individually conducting your research. During the first half of this academic year, I spent hundreds of hours reading articles and books on my topic to make sure I understood the literature. Around halfway through the year, I wrote my literature review based upon that reading, which helped me set my eventual dissertation within the broader literature on my topic.

After the holiday break, I began working on my upgrade chapter, which is an original piece of research we is required to submit as part of our upgrade dossier in June. At first, I spent a lot of time reading my primary source materials I had already collected and organised them so they were ready to go when I began writing. Around March, I started writing the chapter, which I have been continuously working on until now. At the moment, I am putting the finishing touches on it and will be submitting it in a few weeks. It will feel great to finally submit it!

T he first year of the PhD is a great time to read, think, and write before other responsibilities come into play . If you are going into your first year of a PhD next year, I would encourage you to read widely, strongly consider about where you will fit into the scholarship, and be bold in your arguments. Don’t be afraid to have a different viewpoint and make your case. After all, that is what academia is all about.

About the author

My name is Grant Golub and I'm a PhD candidate in the Department of International History at LSE. My research focuses on US foreign relations and grand strategy, diplomatic history, and Anglo-American relations.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Related Posts

6 Ways to Cheer You Up from the Post-Holiday Blues

January 20th, 2023.

3 More Course Recommendations for History Masters Students Next Year

July 14th, 2020.

How have LSE resources helped my dissertation?

July 3rd, 2023.

Preparing Your Second Essays

February 7th, 2021.

Bad Behavior has blocked 1591 access attempts in the last 7 days.

The PhD Experience

- Call for Contributions

What is the first year of a PhD actually like?

By Fraser Raeburn |

It’s that time of year again, with a host of bright-eyed, rosy-cheeked young things preparing to saddle up and get started on their PhDs. None of them know what they’re in for. Not in the cynical, ‘abandon-hope-all-ye-who-enter-here’ sense, but because the first year of a PhD is a curiously undefined, mysterious thing. Once the dust settles from the orientation activities, the welcome speeches have been made and you’ve worked out where your workspace is, what next?

There is of course no single answer. Your PhD is unique, just like everyone else’s. But in the humanities at least, there tends to be a natural rhythm to the first year. It goes something like this:

- Being politely ignored

The first steps are the hardest, and the point at which you need the most guidance. Fortunately, guidance is built into the PhD through the oversight of one or more supervisors . Less fortunately, the beginning of the academic year is the most difficult time to get the attention of any moderately senior academic. They have classes to plan and teach, have to deal with dozens of mildly clueless new undergrads and a backlog of admin work that they have carefully ignored over the summer. Meeting with you – and more to the point, meeting with their brain functions fully engaged – is not at the top of their to-do list. This is not because they don’t like you, or aren’t interested (for most academics, PhD supervision is the most interesting and rewarding part of their job), but they know that you have plenty of time and can wait a little, unlike all their other problems. Be patient. Get to know the other PhDs . It shouldn’t be more than a week or two.

The literature review is a constant in most disciplines, and a fair chunk of your time will be spent explaining how other people have previously understood/explained/been blatantly wrong about your topic. Don’t be surprised if the first thing your supervisor asks you to do is to read everything of relevance to your proposed research, digest it and write about it. This is almost universally considered to be tedious, maybe even pointless. There’s no way you can include everything that will be relevant to the final project, not to mention that there will be new publications by the time you are writing up the actual thesis, potentially rendering your early analysis obsolete. You signed up to a PhD in order to do research, and this won’t feel like it.

It’s more useful to think of the literature review as insurance, for both you and your supervisor. From your supervisor’s perspective, they probably aren’t completely up to date with your specific topic, so you handily summarising the state of the field is a useful starting point for them to engage with your future work. Moreover, it’s not that hard to come up with a research proposal – especially as it may not have been looked over by an actual expert in the topic during the application process. Engaging with current research forces you to think about how your own project will fit in, and will give your supervisor some added faith that your research is well-directed and meaningful. From their – and your – perspective, it’s much better to discover whether your proposed approach has any holes in it before you actually start the research.

- Popping cherries

There’s a few aspects of academic life that you may not have encountered yet. That’s not to say that you need to start doing everything at once – this isn’t a box-ticking exercise – but it’s a good idea to be on the look out for new things to try. You may have never attended a conference or given a paper: your first year is often a great time to find a safe space to experiment, float new ideas and try out new techniques . You may embark on your first research trip . You might also look into ways to get involved in the academic community. Making yourself a Twitter account and following your academic idols is a good first step. There will also be plenty of people looking to exploit your free time give you opportunities, offering the chance to do things like organising conferences and seminar series, getting involved in blogging projects or help running research networks . Not only do these opportunities let you develop skills and make contacts, it’s also never too early to think about what your CV will look like at the end of the PhD. Someone, at some point, will tell you exactly how hard it is to land an academic job. They’re not wrong. Get started early.

- Gearing up to be reviewed

Most PhD programmes require passing a review after your first year in order to confirm that you’re making satisfactory progress, and much of your first year will be spent working towards fulfilling these requirements. Technically, you are only a PhD ‘candidate’ after passing this review, before then you’re on probation and can’t aspire to such lofty titles. These reviews vary a great deal depending on your progression, your supervisors and your project. Usually, you will submit a portfolio of work: the aforementioned lit review, a provisional chapter draft, conference papers, plans for the future – whatever makes sense for your project. For most, this will be a relatively useful exercise in dealing with and responding to criticism. It is also useful to make sure that Stockholm Syndrome isn’t setting in between you and your supervisor, with someone outside the supervision team there to offer a fresh perspective. For some, however, the review can be problematic . If so, remember that you aren’t alone, and that the review is an opportunity to uncover issues and fix them before they prove fatal to your PhD.

Your first year may or may not look like this – if it doesn’t, it’s important to remember that there’s no one blueprint for PhD success. In fact, one of the most important habits to lose is the constant need to compare yourself to others that many of us develop in the competitive world of taught degrees. Never, ever feel inadequate because someone has done something you haven’t, finds something easier than you do or seems to have progressed further than you. If you can manage that, you’re already halfway to surviving your PhD.

Fraser has just entered the third year of his History PhD at the University of Edinburgh, a source of considerable angst. If anyone out there has a guide to your third year, please get in touch . You can find him in dark corners of the internet like Twitter and academia.edu .

Pubs and Publications is recruiting! If you have what it takes* you can read more and apply here .

* a moderate amount of free time

(Cover image, (cc) https://www.flickr.com/photos/dullhunk; Image 1, (cc) https://www.flickr.com/photos/katerha; Image 2 (cc) www.pixabay.com)

Share this post:

September 19, 2016

Uncategorized

How-to , networking , phd , research , time management

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Search this blog

Recent posts.

- Seeking Counselling During the PhD

- Teaching Tutorials: How To Mark Efficiently

- Prioritizing Self-care

- The Dream of Better Nights. Or: Troubled Sleep in Modern Times.

- Teaching Tutorials – How To Make Discussion Flow

Recent Comments

- sacbu on Summer Quiz: What kind of annoying PhD candidate are you?

- Susan Hayward on 18 Online Resources and Apps for PhD Students with Dyslexia

- Javier on My PhD and My ADHD

- timgalsworthy on What to expect when you’re expected to be an expert

- National Rodeo on 18 Online Resources and Apps for PhD Students with Dyslexia

- Comment policy

- Content on Pubs & Publications is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.5 Scotland

© 2024 Pubs and Publications — Powered by WordPress

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑

A Pocket Guide to First Year Annual Review

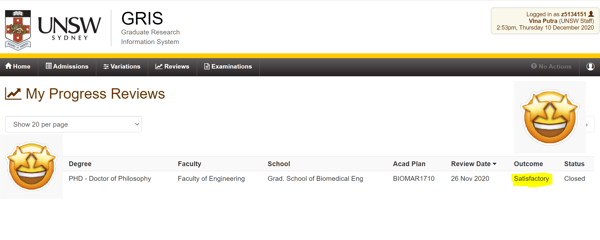

Annual reviews are deemed important points of progression during the PhD journey.

In addition to being a progression review, the annual review helps to support students to successfully conti nue and complete their PhD journey. F or first – year PhD students, annual reviews may be considered one of the most important points in their year, more so than subsequent annual reviews. They are one of the two major points of review for a first – year doctoral candidate , the first being 10-week report. Possible outcomes of the review mainly include: (1) confirmation of registration for PhD and progression to year 2 , (2) repeating the review within 3 months , or (3) registration to a different programme like an MScR or discontinuation of registration entirely.

With Annual Review frenzy right around the corner and most first – year PhD students eagerly waiting for their assessments , here is a pocket guide to ‘ survive ’ the first-year annual review.

1. Keep the timeline of your review in mind-

Annual reviews typically occur between 9 to 12 months of the programme starting date. Hence, it is advisable to keep in mind the timeline for the first year and plan accordingly.

2. Follow the proper procedure of the Annual Review-

Each subject area within the School might have slightly different procedures when it comes to conducting the annual review ; h owever, it generally consists of finalizing the date of the review, filling out a form on EUCLID (in the Student Record section in MyEd ), submitting a paper before the said date , and giving a short presentation on the day of the review (although not required, but most reviews involve some form of presentation) .

For more details about the procedure of the Annual Review, please visit: https://www.ed.ac.uk/files/atoms/files/copsupervisorsresearchstudents.pdf

3. Ensure open channels of communication with the supervisors-

All PhD students are , at a minimum, allotted two supervisors — both a primary and secondary super visor or co-supervisors . The supervisory team is one of the most important support structures throughout one’s PhD progression . It is imperative (and cannot be stressed enough) to maintain honest and open communication with one’ s supervisory team at all times . If you are facing a ny problem or feeling overwhelmed, they should be the first people to know about it.

I think you can’t help but compare yourself to other PGRs, but it is really important to remember that every supervisor and critical friend has different expectations and preferences. Definitely talk to your supervisory t eam and your critical friend about how to organize the review process! For some it might be more formal, but my Annual Review was very ca sual and more of a conversation with colleagues. -Anonymous 1

4. Maintain consistency-

Now, we all know that we never end our PhD’s with the same research topic that we start with, rather, it is a whole process of evolution and deliberation of thoughts and ideas. However, in cases where we wish to make a radical change from one research interest to another, it is advisable to consult o n e ’ s supervisory team before doing so because , in some cases, they might not specialize in the changed/ suggested research topic or they would want to include other supervisors on the team to better assist with the new research topic ; thus, it ’s always best to keep them in the loop.

I was very surprised, and pleased, when by the time I had to present my annual review, I realized my project had slightly changed from what I initially proposed. This process was a bit scary, but my supervisors told me that it was natural and even expected to have a change in thoughts during the whole process of the PhD. The first year wasn’t an exception, as they expected refinement of the project and a more critical development of it. In my case the core topic was the same, but the intricacies of it and the methodology is what changed. -Anonymous 2

5. Critical Friend-

As part of the annual review process, each PhD student gets a ‘ critical friend ’ allotted to their research . The Critical Friend will be involved with the supervision team in reviewing the annual progress and might offer occasional advice to the student regarding the project during the following years. One of the most important roles of the critical friend is to provide feedback following the first-year annual review and subsequent annual reviews. The critical friend is someone the student can speak with if they are facing difficulties in supervision that they would like support with.

In my particular case, having a critical friend provided a sense of stress as you are showing your project to an external person for the first time, but also, when I knew her expertise in both the topic and the methodology, I felt relieved as I knew her feedback was going to make my project more rigorous and rich. -Anonymous 2

6. Keep in constant touch with the PGR community-

The PhD journey can become quite isolated, especially when o n e’s colleagues are also consumed by their own research projects ; however, it is important, especially during unpre c e dented uncertain times , to consistently interact with other PhD students to know that you are most definitely not alone! The school has appointed ‘PGR Reps’ who are designated to address concerns of the rest of the PGR community — while they cannot actively help your concerns or change your situation, they can definitely provide a signpost in the right direction.

I did a peer-presentation for my 1st year review and attended a couple. The PhD students who had been through the process gave some feedback and asked a few questions. I asked some people to read my first-year review draft, give me their comments and I also asked a couple of them to share their first-year review documents. -Anonymous 3 One of the best advices I got from my peers and supervisors was to write small pieces of thoughts, paper summaries and rationales for decision making processes since the very beginning of my PhD as this would be material you can always refer to when you present your annual review. It will give structure to your thoughts and will bring more material to your PhD. Keeping a journal of your activities and small pieces of writing is a good practice whilst doing a PhD. – Anonymous 2

7. Be realistic in your approach-

While it is easy to get carried away with your project — because let’s be real, it is our baby in the making — it is essential to be realistic. Keeping in mind both p roject feasibility and situational circumstances is important . It is highly important to be pragmatic about timelines and , if you tend to get overwhelmed, do not hesitate to apply for extensions and special circumstances . The school provides a lot of resources for the same.

When I was in my first year, my supervisors asked m e how many PhDs I was in tending to do. You probably can’t change the whole world with your project, but you can do it in a way that it changes you – use your PhD to learn new skills and to challenge yourself ! I had to learn that a well-designed project about a small topic area is better than a big superficial project. -Anonymous 1

8. Maintain a healthy work-life balance-

All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy! Getting a PhD is a long journey; hence, it is highly important to maintain a life outside your PhD and research. Indulging in other activities and hobbies will not only relax you but also help instill some transferable skills which can prove to be important both for personal and professional development. So, it is imperative for you to have a life outside the office, something which doesn’t involv e your research and help you unwind.

Very often you hear stories (I know I did) that most of the first annual review ends up being your first chapter, but this puts a lot of pressure to produce something that is ‘PhD Thesis’ quality. The reality is that PhDs are dynamic, literature is dynamic, so there is no way you can just copy paste your 1st annual review in your first chapter 3 years later, and that’s ok. Don’t see your annual review as a PhD chapter. See it as a work in progress! -Anonymous 4

Remember, the above list is quite explorative , and there is no ‘One Size Fits All’ formula. The University has an Advice Place ( https://www.eusa.ed.ac.uk/support_and_advice/the_advice_place/ ) to help students address both academic and non-academic concerns. While e veryone has different plans of action or support which might work for them , this small list of simple ‘ do’s and don’t s ’ might come in handy for those who are going to appear for their annual review in the coming months. Although the first year review may seem quite daunting and stressful, it acts as an important reality check for the students to plan out the subsequent years; getting feedback from both the supervisory team and the critical friend, proves quite useful for the rest of the years to come.

To learn more about the Annual Review Process, please click on the link below (EASE Login Required) : https://www.learn.ed.ac.uk/webapps/blackboard/content/listContent.jsp?course_id=_17186_1&content_id=_617596_1

One comment

Many thanx for sharing this!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and site URL in my browser for next time I post a comment.

HTML Text A Pocket Guide to First Year Annual Review / Research Bow by blogadmin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0

Plain text A Pocket Guide to First Year Annual Review by blogadmin @ is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0

Report this page

To report inappropriate content on this page, please use the form below. Upon receiving your report, we will be in touch as per the Take Down Policy of the service.

Please note that personal data collected through this form is used and stored for the purposes of processing this report and communication with you.

If you are unable to report a concern about content via this form please contact the Service Owner .

- Schools & departments

Writing your PhD: Reviewing the Literature

This course is intended for PhD students in their second year.

Course Content and Unit Aims

Criteria for success, purpose, and citation skills

- To explore the criteria for a successful literature review, as proposed by the literature and by University of Edinburgh academics.

- To discuss the purposes of a literature review.

- To raise awareness of citation practices, including direct quotation, paraphrase, summary, and the avoidance of plagiarism.

- To provide practice in paraphrasing and summarising sources.

Organisation and Structure

- To explore different potential patterns for organising a literature review.

- To examine (and practise writing) introductions, transitions and conclusions within a literature review chapter.

- To raise awareness of ways of identifying a research gap.

Expressing Your Voice and Writing Critically

- To explore how sources can be used to support your own position.

- To focus on language features which can be used to guide your reader through your text while making your argument clear.

- To discuss ways of expressing a stance towards previous studies, and explore appropriate relevant language features.

- To examine the use of personal pronouns in a literature review.

Synthesising Sources

- To explore the language and structure of an effective definition.

- To practise synthesising definitions, where more than one exists in the literature.

- To explore ways of organising a literature review thematically rather than by author/study.

- To identify appropriate language used to make the organisation of your literature review explicit.

- To give you practice in synthesising sources.

- You will have the opportunity for a one-to-one on-line tutorial with your teacher, to discuss any remaining questions you may have.

Course Days/times

- In-person – Thursdays 14:00 - 16:00

- Online – Fridays 11:00 - 12:00

The in-person course will be held at both Holyrood Campus and King's Buildings.

Teaching Methods and Learning Outcomes

The course involves: discussion of aspects of reviewing literature; analysing sample extracts from University of Edinburgh doctoral theses; expanding your repertoire of useful academic English expressions; drafting short pieces of writing.

Your tutor will meet you for a class once per week, either on-line or in-person, depending which option you have chosen. If you choose the on-line version of the course, you will listen to a brief introductory lecture and work through a series of tasks before the class. You can expect to spend around 3 hours per week altogether to fully benefit from this course .

After the class, you will write a short assignment, which you should send to your tutor, who will respond with feedback on your writing, focusing on overall clarity, style, the use of sources, organisation, and linguistic appropriacy.

In the final week (week 5) of the course, you will have the opportunity for a one-to-one online tutorial with your tutor to discuss any remaining questions you may have.

By the end of the course students should have a better understanding of:

- ways of structuring a literature review

- appropriate language for reviewing literature

- the skills involved in summarising and paraphrasing

- the skills involved in synthesising sources

- ways of expressing critical evaluation

- ways of expressing authorial voice

Eligibility

PhD students in their second year, or who have passed their First Year Board, and students doing MSc by research in their second semester. Final year students are also eligible, if they have not had the opportunity of taking this course earlier.

This article was published on 2023-11-23

Study at Cambridge

About the university, research at cambridge.

- Undergraduate courses

- Events and open days

- Fees and finance

- Postgraduate courses

- How to apply

- Postgraduate events

- Fees and funding