Developing a Thesis Statement

Many papers you write require developing a thesis statement. In this section you’ll learn what a thesis statement is and how to write one.

Keep in mind that not all papers require thesis statements . If in doubt, please consult your instructor for assistance.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement . . .

- Makes an argumentative assertion about a topic; it states the conclusions that you have reached about your topic.

- Makes a promise to the reader about the scope, purpose, and direction of your paper.

- Is focused and specific enough to be “proven” within the boundaries of your paper.

- Is generally located near the end of the introduction ; sometimes, in a long paper, the thesis will be expressed in several sentences or in an entire paragraph.

- Identifies the relationships between the pieces of evidence that you are using to support your argument.

Not all papers require thesis statements! Ask your instructor if you’re in doubt whether you need one.

Identify a topic

Your topic is the subject about which you will write. Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic; or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper.

Consider what your assignment asks you to do

Inform yourself about your topic, focus on one aspect of your topic, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts, generate a topic from an assignment.

Below are some possible topics based on sample assignments.

Sample assignment 1

Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II.

Identified topic

Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis

This topic avoids generalities such as “Spain” and “World War II,” addressing instead on Franco’s role (a specific aspect of “Spain”) and the diplomatic relations between the Allies and Axis (a specific aspect of World War II).

Sample assignment 2

Analyze one of Homer’s epic similes in the Iliad.

The relationship between the portrayal of warfare and the epic simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64.

This topic focuses on a single simile and relates it to a single aspect of the Iliad ( warfare being a major theme in that work).

Developing a Thesis Statement–Additional information

Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic, or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper. You’ll want to read your assignment carefully, looking for key terms that you can use to focus your topic.

Sample assignment: Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II Key terms: analyze, Spain’s neutrality, World War II

After you’ve identified the key words in your topic, the next step is to read about them in several sources, or generate as much information as possible through an analysis of your topic. Obviously, the more material or knowledge you have, the more possibilities will be available for a strong argument. For the sample assignment above, you’ll want to look at books and articles on World War II in general, and Spain’s neutrality in particular.

As you consider your options, you must decide to focus on one aspect of your topic. This means that you cannot include everything you’ve learned about your topic, nor should you go off in several directions. If you end up covering too many different aspects of a topic, your paper will sprawl and be unconvincing in its argument, and it most likely will not fulfull the assignment requirements.

For the sample assignment above, both Spain’s neutrality and World War II are topics far too broad to explore in a paper. You may instead decide to focus on Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis , which narrows down what aspects of Spain’s neutrality and World War II you want to discuss, as well as establishes a specific link between those two aspects.

Before you go too far, however, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts. Try to avoid topics that already have too much written about them (i.e., “eating disorders and body image among adolescent women”) or that simply are not important (i.e. “why I like ice cream”). These topics may lead to a thesis that is either dry fact or a weird claim that cannot be supported. A good thesis falls somewhere between the two extremes. To arrive at this point, ask yourself what is new, interesting, contestable, or controversial about your topic.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times . Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Derive a main point from topic

Once you have a topic, you will have to decide what the main point of your paper will be. This point, the “controlling idea,” becomes the core of your argument (thesis statement) and it is the unifying idea to which you will relate all your sub-theses. You can then turn this “controlling idea” into a purpose statement about what you intend to do in your paper.

Look for patterns in your evidence

Compose a purpose statement.

Consult the examples below for suggestions on how to look for patterns in your evidence and construct a purpose statement.

- Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis

- Franco turned to the Allies when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from the Axis

Possible conclusion:

Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: Franco’s desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power.

Purpose statement

This paper will analyze Franco’s diplomacy during World War II to see how it contributed to Spain’s neutrality.

- The simile compares Simoisius to a tree, which is a peaceful, natural image.

- The tree in the simile is chopped down to make wheels for a chariot, which is an object used in warfare.

At first, the simile seems to take the reader away from the world of warfare, but we end up back in that world by the end.

This paper will analyze the way the simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64 moves in and out of the world of warfare.

Derive purpose statement from topic

To find out what your “controlling idea” is, you have to examine and evaluate your evidence . As you consider your evidence, you may notice patterns emerging, data repeated in more than one source, or facts that favor one view more than another. These patterns or data may then lead you to some conclusions about your topic and suggest that you can successfully argue for one idea better than another.

For instance, you might find out that Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis, but when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from them, he turned to the Allies. As you read more about Franco’s decisions, you may conclude that Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: his desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power. Based on this conclusion, you can then write a trial thesis statement to help you decide what material belongs in your paper.

Sometimes you won’t be able to find a focus or identify your “spin” or specific argument immediately. Like some writers, you might begin with a purpose statement just to get yourself going. A purpose statement is one or more sentences that announce your topic and indicate the structure of the paper but do not state the conclusions you have drawn . Thus, you might begin with something like this:

- This paper will look at modern language to see if it reflects male dominance or female oppression.

- I plan to analyze anger and derision in offensive language to see if they represent a challenge of society’s authority.

At some point, you can turn a purpose statement into a thesis statement. As you think and write about your topic, you can restrict, clarify, and refine your argument, crafting your thesis statement to reflect your thinking.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Compose a draft thesis statement

If you are writing a paper that will have an argumentative thesis and are having trouble getting started, the techniques in the table below may help you develop a temporary or “working” thesis statement.

Begin with a purpose statement that you will later turn into a thesis statement.

Assignment: Discuss the history of the Reform Party and explain its influence on the 1990 presidential and Congressional election.

Purpose Statement: This paper briefly sketches the history of the grassroots, conservative, Perot-led Reform Party and analyzes how it influenced the economic and social ideologies of the two mainstream parties.

Question-to-Assertion

If your assignment asks a specific question(s), turn the question(s) into an assertion and give reasons why it is true or reasons for your opinion.

Assignment : What do Aylmer and Rappaccini have to be proud of? Why aren’t they satisfied with these things? How does pride, as demonstrated in “The Birthmark” and “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” lead to unexpected problems?

Beginning thesis statement: Alymer and Rappaccinni are proud of their great knowledge; however, they are also very greedy and are driven to use their knowledge to alter some aspect of nature as a test of their ability. Evil results when they try to “play God.”

Write a sentence that summarizes the main idea of the essay you plan to write.

Main idea: The reason some toys succeed in the market is that they appeal to the consumers’ sense of the ridiculous and their basic desire to laugh at themselves.

Make a list of the ideas that you want to include; consider the ideas and try to group them.

- nature = peaceful

- war matériel = violent (competes with 1?)

- need for time and space to mourn the dead

- war is inescapable (competes with 3?)

Use a formula to arrive at a working thesis statement (you will revise this later).

- although most readers of _______ have argued that _______, closer examination shows that _______.

- _______ uses _______ and _____ to prove that ________.

- phenomenon x is a result of the combination of __________, __________, and _________.

What to keep in mind as you draft an initial thesis statement

Beginning statements obtained through the methods illustrated above can serve as a framework for planning or drafting your paper, but remember they’re not yet the specific, argumentative thesis you want for the final version of your paper. In fact, in its first stages, a thesis statement usually is ill-formed or rough and serves only as a planning tool.

As you write, you may discover evidence that does not fit your temporary or “working” thesis. Or you may reach deeper insights about your topic as you do more research, and you will find that your thesis statement has to be more complicated to match the evidence that you want to use.

You must be willing to reject or omit some evidence in order to keep your paper cohesive and your reader focused. Or you may have to revise your thesis to match the evidence and insights that you want to discuss. Read your draft carefully, noting the conclusions you have drawn and the major ideas which support or prove those conclusions. These will be the elements of your final thesis statement.

Sometimes you will not be able to identify these elements in your early drafts, but as you consider how your argument is developing and how your evidence supports your main idea, ask yourself, “ What is the main point that I want to prove/discuss? ” and “ How will I convince the reader that this is true? ” When you can answer these questions, then you can begin to refine the thesis statement.

Refine and polish the thesis statement

To get to your final thesis, you’ll need to refine your draft thesis so that it’s specific and arguable.

- Ask if your draft thesis addresses the assignment

- Question each part of your draft thesis

- Clarify vague phrases and assertions

- Investigate alternatives to your draft thesis

Consult the example below for suggestions on how to refine your draft thesis statement.

Sample Assignment

Choose an activity and define it as a symbol of American culture. Your essay should cause the reader to think critically about the society which produces and enjoys that activity.

- Ask The phenomenon of drive-in facilities is an interesting symbol of american culture, and these facilities demonstrate significant characteristics of our society.This statement does not fulfill the assignment because it does not require the reader to think critically about society.

Drive-ins are an interesting symbol of American culture because they represent Americans’ significant creativity and business ingenuity.

Among the types of drive-in facilities familiar during the twentieth century, drive-in movie theaters best represent American creativity, not merely because they were the forerunner of later drive-ins and drive-throughs, but because of their impact on our culture: they changed our relationship to the automobile, changed the way people experienced movies, and changed movie-going into a family activity.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast-food establishments, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize America’s economic ingenuity, they also have affected our personal standards.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast- food restaurants, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize (1) Americans’ business ingenuity, they also have contributed (2) to an increasing homogenization of our culture, (3) a willingness to depersonalize relationships with others, and (4) a tendency to sacrifice quality for convenience.

This statement is now specific and fulfills all parts of the assignment. This version, like any good thesis, is not self-evident; its points, 1-4, will have to be proven with evidence in the body of the paper. The numbers in this statement indicate the order in which the points will be presented. Depending on the length of the paper, there could be one paragraph for each numbered item or there could be blocks of paragraph for even pages for each one.

Complete the final thesis statement

The bottom line.

As you move through the process of crafting a thesis, you’ll need to remember four things:

- Context matters! Think about your course materials and lectures. Try to relate your thesis to the ideas your instructor is discussing.

- As you go through the process described in this section, always keep your assignment in mind . You will be more successful when your thesis (and paper) responds to the assignment than if it argues a semi-related idea.

- Your thesis statement should be precise, focused, and contestable ; it should predict the sub-theses or blocks of information that you will use to prove your argument.

- Make sure that you keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Change your thesis as your paper evolves, because you do not want your thesis to promise more than your paper actually delivers.

In the beginning, the thesis statement was a tool to help you sharpen your focus, limit material and establish the paper’s purpose. When your paper is finished, however, the thesis statement becomes a tool for your reader. It tells the reader what you have learned about your topic and what evidence led you to your conclusion. It keeps the reader on track–well able to understand and appreciate your argument.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

Think of yourself as a member of a jury, listening to a lawyer who is presenting an opening argument. You'll want to know very soon whether the lawyer believes the accused to be guilty or not guilty, and how the lawyer plans to convince you. Readers of academic essays are like jury members: before they have read too far, they want to know what the essay argues as well as how the writer plans to make the argument. After reading your thesis statement, the reader should think, "This essay is going to try to convince me of something. I'm not convinced yet, but I'm interested to see how I might be."

An effective thesis cannot be answered with a simple "yes" or "no." A thesis is not a topic; nor is it a fact; nor is it an opinion. "Reasons for the fall of communism" is a topic. "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" is a fact known by educated people. "The fall of communism is the best thing that ever happened in Europe" is an opinion. (Superlatives like "the best" almost always lead to trouble. It's impossible to weigh every "thing" that ever happened in Europe. And what about the fall of Hitler? Couldn't that be "the best thing"?)

A good thesis has two parts. It should tell what you plan to argue, and it should "telegraph" how you plan to argue—that is, what particular support for your claim is going where in your essay.

Steps in Constructing a Thesis

First, analyze your primary sources. Look for tension, interest, ambiguity, controversy, and/or complication. Does the author contradict himself or herself? Is a point made and later reversed? What are the deeper implications of the author's argument? Figuring out the why to one or more of these questions, or to related questions, will put you on the path to developing a working thesis. (Without the why, you probably have only come up with an observation—that there are, for instance, many different metaphors in such-and-such a poem—which is not a thesis.)

Once you have a working thesis, write it down. There is nothing as frustrating as hitting on a great idea for a thesis, then forgetting it when you lose concentration. And by writing down your thesis you will be forced to think of it clearly, logically, and concisely. You probably will not be able to write out a final-draft version of your thesis the first time you try, but you'll get yourself on the right track by writing down what you have.

Keep your thesis prominent in your introduction. A good, standard place for your thesis statement is at the end of an introductory paragraph, especially in shorter (5-15 page) essays. Readers are used to finding theses there, so they automatically pay more attention when they read the last sentence of your introduction. Although this is not required in all academic essays, it is a good rule of thumb.

Anticipate the counterarguments. Once you have a working thesis, you should think about what might be said against it. This will help you to refine your thesis, and it will also make you think of the arguments that you'll need to refute later on in your essay. (Every argument has a counterargument. If yours doesn't, then it's not an argument—it may be a fact, or an opinion, but it is not an argument.)

This statement is on its way to being a thesis. However, it is too easy to imagine possible counterarguments. For example, a political observer might believe that Dukakis lost because he suffered from a "soft-on-crime" image. If you complicate your thesis by anticipating the counterargument, you'll strengthen your argument, as shown in the sentence below.

Some Caveats and Some Examples

A thesis is never a question. Readers of academic essays expect to have questions discussed, explored, or even answered. A question ("Why did communism collapse in Eastern Europe?") is not an argument, and without an argument, a thesis is dead in the water.

A thesis is never a list. "For political, economic, social and cultural reasons, communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" does a good job of "telegraphing" the reader what to expect in the essay—a section about political reasons, a section about economic reasons, a section about social reasons, and a section about cultural reasons. However, political, economic, social and cultural reasons are pretty much the only possible reasons why communism could collapse. This sentence lacks tension and doesn't advance an argument. Everyone knows that politics, economics, and culture are important.

A thesis should never be vague, combative or confrontational. An ineffective thesis would be, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because communism is evil." This is hard to argue (evil from whose perspective? what does evil mean?) and it is likely to mark you as moralistic and judgmental rather than rational and thorough. It also may spark a defensive reaction from readers sympathetic to communism. If readers strongly disagree with you right off the bat, they may stop reading.

An effective thesis has a definable, arguable claim. "While cultural forces contributed to the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, the disintegration of economies played the key role in driving its decline" is an effective thesis sentence that "telegraphs," so that the reader expects the essay to have a section about cultural forces and another about the disintegration of economies. This thesis makes a definite, arguable claim: that the disintegration of economies played a more important role than cultural forces in defeating communism in Eastern Europe. The reader would react to this statement by thinking, "Perhaps what the author says is true, but I am not convinced. I want to read further to see how the author argues this claim."

A thesis should be as clear and specific as possible. Avoid overused, general terms and abstractions. For example, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because of the ruling elite's inability to address the economic concerns of the people" is more powerful than "Communism collapsed due to societal discontent."

Copyright 1999, Maxine Rodburg and The Tutors of the Writing Center at Harvard University

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.3: What is a Thesis Statement?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 12059

- Kathy Boylan

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Once the topic has been narrowed to a workable subject, then determine what you are going to say about it; you need to come up with your controlling or main idea. A thesis is the main idea of an essay. It communicates the essay’s purpose with clear and concise wording and indicates the direction and scope of the essay. It should not just be a statement of fact nor should it be an announcement of your intentions. It should be an idea, an opinion of yours that needs to be explored, expanded, and developed into an argument .

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick ; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence somewhere in the introductory paragraph that presents the writer’s argument to the reader. However, as essays get longer, a sentence alone is usually not enough to contain a complex thesis. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the readers of the logic of their interpretation.

If an assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that the writer needs a thesis statement because the instructor may assume the writer will include one. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively.

How do I get a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. (See chapter on argument for more detailed information on building an argument.) Once you have done this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis,” a basic or main idea, an argument that you can support with evidence. It is deemed a “working thesis” because it is a work in progress, and it is subject to change as you move through the writing process. Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic to arrive at a thesis statement.

For example, there is the question strategy. One way to start identifying and narrowing a thesis idea is to form a question that you want to answer. For example, if the starting question was “Do cats have a positive effect on people with depression? If so, what are three effects? The question sends you off to explore for answers. You then begin developing support. The first answer you might find is that petting cats lowers blood pressure, and, further question how that works. From your findings (research, interviews, background reading, etc.), you might detail how that happens physically or you might describe historical evidence. You could explain medical research that illustrates the concept. Then you have your first supporting point — as well as the first prong of your thesis: Cats have a positive effect on people with depression because they can lower blood pressure.... When you start with a specific question and find the answers, the argument falls into place. The answer to the question becomes the thesis, and how the answer was conceived becomes the supporting points (and, usually, the topic sentences for each point).

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there is time, run it by the instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center ( https://tinyurl.com/ybqafrbf ) to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own.

When reviewing the first draft and its working thesis, ask the following:

TOPIC + CLAIM = THESIS STATEMENT

- Animals + Dogs make better pets than cats. =When it comes to animals, dogs make better pets than cats because they are more trainable, more social, and more empathetic.

- Movies & Emotions + Titanic evoked many emotions. = The movie Titanic evoked many emotions from an audience.

- Arthur Miller & Death of a Salesman + Miller’s family inspired the Loman family. = Arthur Miller’s family and their experiences during the Great Depression inspired the creation of the Loman family in his play Death of a Salesman .

( https://tinyurl.com/y8sfjale ).

Exercise: Creating Effective Thesis Statements

Using the formula, create effective thesis statements for the following topics:

- Drone Technology

- Helicopter Parents

Then have a partner check your thesis statements to see if they pass the tests to be strong thesis statements.

Once a working thesis statement has been created, then it is time to begin building the body of the essay. Get all of the key supporting ideas written down, and then you can begin to flesh out the body paragraphs by reading, asking, observing, researching, connecting personal experiences, etc. Use the information from below to maintain the internal integrity of the paragraphs and smooth the flow of your ideas.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8 Chapter 8: Organizing and Outlining

Victoria Leonard, College of the Canyons

Adapted by William Kelvin, Professor of Communication Studies, Katharine O’Connor, Ph.D., and Jamie C. Votraw, Professor of Communication Studies, Florida SouthWestern State College

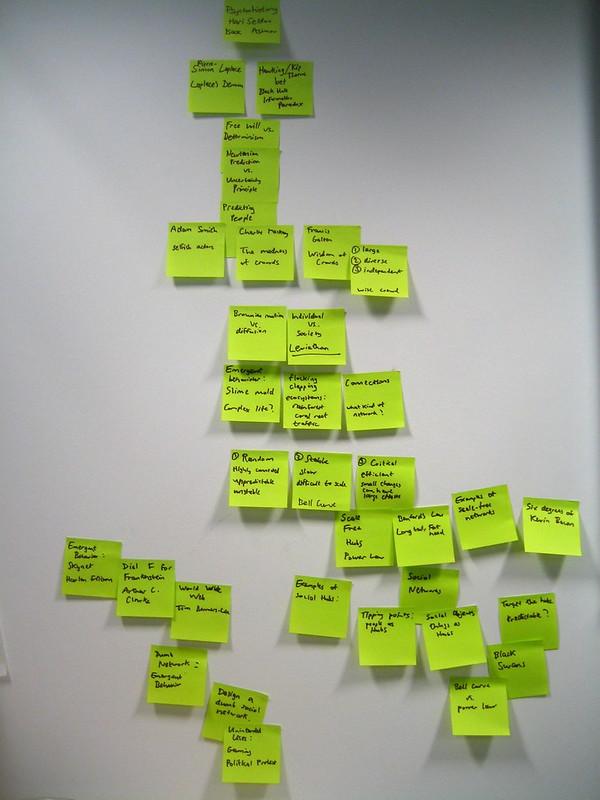

Figure 8.1: Outlining with Post it Notes 1

Introduction

One of your authors remembers taking an urban studies course in college. The professor was incredibly knowledgeable and passionate about the subject. Do you think that alone made her want to go to class? Unfortunately not. As great as this professor was in so many ways, the lectures were not organized. As much as she tried to take great notes and follow along, it felt like a hopeless task. Having a great topic that you are passionate about is important, but organizing your speech so that the audience can follow along is vital to the success of your speech.

When students are faced with developing a speech, they face the same challenges as a student asked to write an essay. Although the end product may be different in that you are not writing an essay or turning one in, you will go through much of the same process as you would in writing an essay.

Before you get too far into the writing process, it is important to know what steps you will have to take to write your speech. Note that the speech-writing process is formulaic: it is based on time-honored principles of rhetoric established thousands of years ago. Your initial preparation work will include the following:

- Selecting a topic

- Writing a general purpose

- Writing a specific purpose

- Writing a thesis statement

- Selecting main points

- Writing a preview statement

- Writing the body of the speech

This chapter will explain each of these steps so that you can create a thorough and well-written speech. As with anything we do that requires effort, the more you put in, the more you will get out of the writing process, in terms of both your education and your grade.

The Speech Topic, General Purpose, Specific Purpose, and Thesis

Selecting a topic.

We all want to know that our topics will be interesting to our audience. If you think back to Chapter 5, Identifying Topic, Purpose, and Audience, you will recall how important it is to be audience-centered. Does this mean that you cannot talk about a topic that your audience is unfamiliar with? No, what it does mean is that your goal as a speaker is to make that topic relevant to the audience. Whether you are writing an informative speech on earthquakes or the singer Jhené Aiko, you will need to make sure that you approach the speech in a way that helps your speech resonate with the audience. Although many of you would not have been alive when Hurricane Andrew hit Florida in 1992, this is an important topic to people who live in hurricane zones. Explaining hurricanes and hurricane preparation would be a great way to bring this topic alive for people who may not have lived through this event. Similarly, many audience members may be unfamiliar with Jhené Aiko, and that allows you to share information about her that might lead someone to want to check out her music.

If you are writing a persuasive speech, you might approach your topic selection differently. Think about what is happening in the world today. You can look at what affects you and your peers at a local, state, national, or global level. Whether you believe that gun violence is important to address because it is a problem at the national level, or you wish to address parking fees on your campus, you will have given thought to what is important to your audience. As Chapter 2 explained, your topics must fulfill the ethical goals of the speech. If you are ethical and select a topic you care about and make it relevant for the audience, you are on the right track.

Here are some questions that might help you select a topic:

- What are some current trends in music or fashion?

- What hobbies do I have that might be interesting to others?

- What objects or habits do I use every day that are beneficial to know about?

- What people are influencing the world in social media or politics?

- What authors, artists, or actors have made an impact on society?

- What events have shaped our nation or our world?

- What political debates are taking place today?

- What challenges do we face as a society or species?

- What health-related conditions should others be aware of?

- What is important for all people to be aware of in your community?

Once you have answered these questions and narrowed your responses, you are still not done selecting your topic. For instance, you might have decided that you really care about dogs. This is a very broad topic and could easily lead to a dozen different speeches. Now you must further narrow down the topic in your purpose statements.

Writing the Purpose Statements

Purpose statements allow you to do two things. First, they allow you to focus on whether you are fulfilling the assignment. Second, they allow you to narrow your topic so that you are not speaking too broadly. When creating an outline for your speech, you should include the general purpose and specific purpose statement at the beginning of your outline.

A general purpose statement is the overarching goal of a speech whether to inform, to persuade, to inspire, to celebrate, to mourn, or to entertain. It describes what your speech goal is, or what you hope to achieve. In public speaking classes, you will be asked to do any of the following: To inform, to persuade, or to entertain . Thus, your general purpose statement will be two words —the easiest points you will ever earn! But these two words are critical for you to keep in mind as you write the speech. Your authors have seen many persuasive speeches submitted inappropriately as informative speeches. Likewise, one author remembers a fascinating “persuasive speech” on the death penalty that never took a stance on the issue or asked the audience to—that would be an informative speech, right? You must always know your broad goal. Your audience should know it, too, and so should your instructor! Knowing your purpose is important because this is what you begin with to build your speech. It is also important to know your general purpose because this will determine your research approach. You might use different sources if you were writing a speech to inform versus to persuade.

A specific purpose statement is consistent with the general purpose of the speech, written according to assignment requirements, and clearly identifies desired audience outcomes. It is a declaration starting with the general purpose and then providing the topic with the precise objectives of the speech. It will be written according to your general purpose. For instance, the home design enthusiast might write the following specific purpose statement: To inform my audience about the pros and cons of flipping houses.

Specific purpose statements are integral in knowing if your speech is narrowed enough or if you need to narrow it further. Consider these examples:

- To inform my audience about musical instruments

- To inform my audience about string instruments

- To inform my audience about the violin

As you can see, the first two examples are far too broad. But is the third purpose statement sufficiently narrow? Will the speaker be covering the violin’s design, physics, history, cost, or how to play it? What do you think about these possible topics?

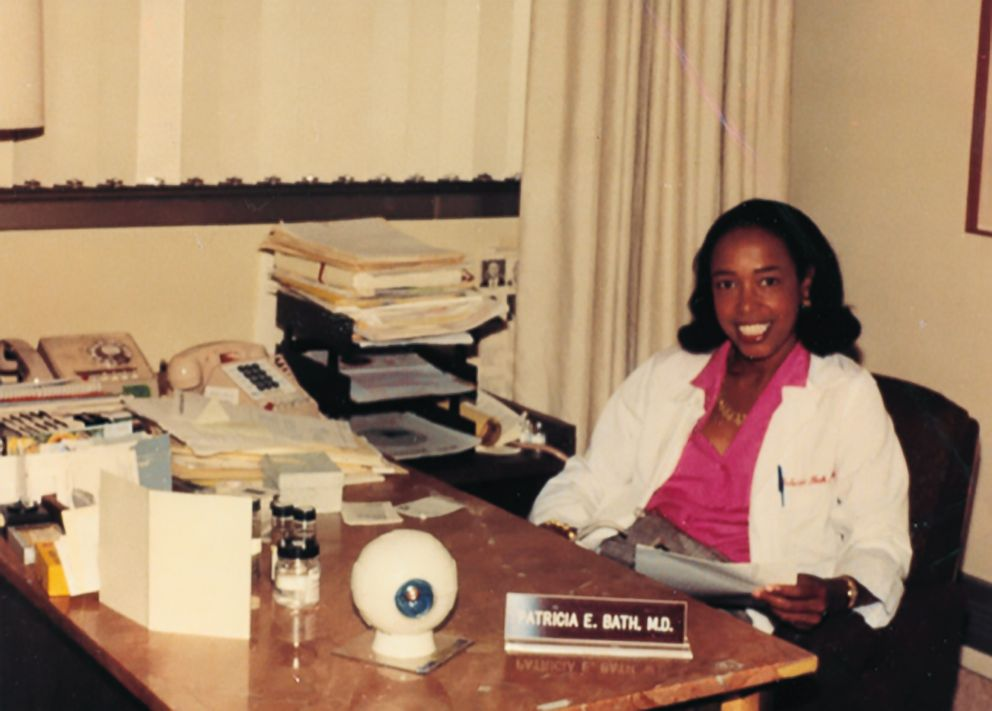

- To inform my audience about the life and contributions of Patricia Bath

- To inform my audience about the invention of the wheelchair

- To inform my audience about the Biloxi Wade-Ins

- To inform my audience about how Fibromyalgia affects the body

Figure 8.2: Dr. Patricia Bath 2

Hopefully, you can see that the examples above would work for an informative speech. They are specific and limited in their scope.

Your instructor will give you a time limit for your speech. Your specific purpose should help you see if you can stay within the time limit. You should put the purpose statements on your outline. Others may only ask you to put these on your topic submission. However, you do not state a general purpose or specific purpose during the delivery of your speech! These are simply guidelines for you as you write and for your instructor as they assess your writing.

Writing the Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is a single, declarative statement that encapsulates the essence of your speech. Just like in essay writing, you want your thesis statement, or central idea, to reveal what your speech is about. Thesis statements can never be written as questions, nor can they include a research citation. The thesis statement is not a list of main points, it is an over-arching idea that encapsulates them all.

Figure 8.3: Portrait of Aut h or, J.R.R. Tolkien 3

As a Lord of the Rings enthusiast, I may choose to write a speech on author J.R.R. Tolkien. Here is an example of what a thesis statement may sound like:

J.R.R. Tolkien is known as the father of modern fantasy literature and became a pop culture icon after his death.

The thesis you just read provides the audience with just enough information to help them know what they will hear ahd learn from your speech.

Selecting Main Points

The main points are the major ideas you want to cover in your speech. Since speeches have time requirements, your outline will always be limited to two to three main points. Many instructors suggest that you have no more than three main points so you can do justice to each idea and stay within the time frame. You will also lose time on each main point describing it in the preview statement, internal transitions, and review of main points in the conclusion. Plus, it can be difficult for audiences to remember many points.

Let’s determine the main points for a short speech using the J.R.R. Tolkien thesis above. Having researched his life, you might come up with an initial list like this:

- Childhood and Background

- Military service

- Literary fame and honors

As interesting as all of these topics are, there is not enough time to speak about each idea. This is where the difficult decision of narrowing a speech comes in. Brainstorming all of the points you could cover would be your first step. Then, you need to determine which of the points would be the most interesting for your audience to hear. There are also creative ways to combine ideas and touch on key points within each main point. You will see how this can be achieved in the next section as we narrow down the number of topics we will discuss about J.R.R. Tolkein.

Writing the Preview Statement

A preview statement is a guide to your speech. This is the part of the speech that literally tells the audience exactly what main points you will cover. If you were to open an app on your phone to get directions to a location, you would be told exactly how to get there. Best of all, you would know what to look for, such as landmarks. A preview statement in a speech fulfills the same goal. It is a roadmap for your speech. Let’s look at how a thesis and preview statement might look for a speech on J.R.R. Tolkien:

Thesis: J.R.R. Tolkien is known as the father of modern fantasy literature and became a pop culture icon after his death.

Preview: First, I will tell you about J.R.R. Tolkien’s humble beginnings. Then, I will describe his rise to literary fame. Finally, I will explain his lasting cultural legacy.

Notice that the thesis statement captures the essence of the speech. The preview concisely names each main point that supports the thesis. You will want to refer to these main point names, or taglines , throughout the speech. This repetition will help audience members remember each main point; use variations of these taglines in your preview statement, when introducing each point, and again in the conclusion.

Always use your words to make the audience feel that they are part of the performance. This makes them feel included and on your side. Also, occasionally audience members will have more expertise than you. Imagine how an expert would feel when you begin your speech with “Today I will teach you about…” when they already know a lot about the subject. Use inclusive language in your preview statement–“Get ready to join me on a fantastic adventure…”

Organizing the Main Points

Once you know what your speech is about, you can begin developing the body of your speech. The body of the speech is the longest and most important part of your speech because it’s where the general purpose is executed, e.g., you inform or persuade with the main points that you listed in your preview statement. In general, the body of the speech comprises about 75% to 80% of the length of your speech. This is where you will present the bulk of your research, evidence, examples, and any other supporting material you have. Chapter 7 will provide you with specifics on how to do research and support your speech.

Several patterns of organization are available to choose from when writing a speech. You should keep in mind that some patterns work only for informative speeches and others for persuasive speeches. The topical, chronological, spatial, or causal patterns discussed here are best suited to informative speeches. The patterns of organization for persuasive speeches will be discussed in Chapter 10.

Topical Pattern

The chronological pattern needed main points ordered in a specific sequence, whereas the topical pattern arranges the information of the speech into different subtopics. For example, you are currently attending college. Within your college, various student services are important for you to use while you are there. You may visit the Richard H. Rush Library and its computer lab, Academic Support Centers, Career Services and the Office of Student Financial Aid.

Figure 8.6: Valencia Campus Library Stacks 6

To organize this speech topically, it doesn’t matter which area you speak about first, but here is how you could organize it:

Topic: Student Services at Florida SouthWestern State College

Thesis Statement: Florida SouthWestern State College has five important student services, which include the library, the library computer lab, Academic Support Centers, Career Services and the Financial Aid office.

Preview : This speech will discuss each of the five important student services that Florida SouthWestern State College offers.

Main Points:

I. The Richard H. Rush Library can be accessed five days a week and online and has a multitude of books, periodicals, and other resources to use.

II.The library’s computer lab is open for students to use for several hours a day, with reliable, high-speed internet connections and webcams.

III.The Academic Support Centers have subject tutors, computers, and study rooms.

IV.CareerSource offers career services both in-person and online, with counseling and access to job listings and networking opportunities.

V. The Office of Student Financial Aid is one of the busiest offices on campus, offering students a multitude of methods by which they can supplement their personal finances by paying for both tuition and books.

Note that many novices appreciate the topical pattern because of its simplicity. However, because there is no internal logic to the ordering of points, the speech writer loses an opportunity to include a mnemonic device (phrasing that helps people remember information) in their performance. Audience members are more likely to remember information if it hangs together in an ordered, logical way, such as the following patterns employ.

Chronological (Temporal) Pattern

When organizing a speech based on time or sequence, you would use a chronological (temporal) pattern of organization. Speeches that look at the history of someone or something, or the evolution of an object or a process could be organized chronologically. For example, you could use this pattern in speaking about President Barack Obama, the Holocaust, the evolution of the cell phone, or how to carve a pumpkin. The challenge of using this pattern is to make sure your speech has distinct main points and that it does not appear to be storytelling.

Figure 8.4: Barack Obama 4

Here is an example of how your main points will help you make sure that the points are clear and distinct:

Topic: President Barack Obama

Specific Purpose: To inform my audience about the life of President Barack Obama.

Thesis: From his humble beginnings, President Barack Obama succeeded in law and politics to become the first African-American president in U.S. history.

Preview: First, let’s look at Obama’s background and career in law. Then, we will look at his rise to the presidency of the United States. Finally, we will explore his accomplishments after leaving the White House.

I. First, let’s look at the early life of Obama and his career as a lawyer and advocate.

II. Second, let’s examine how Obama transitioned from law to becoming the first African-American President of the United States.

III. Finally, let’s explore all that Obama has achieved since he left the White House.

We hope that you can see that the main points clearly define and isolate different parts of Obama’s life so that each point is distinct. Using a chronological pattern can also help you with other types of informative speech topics.

Figure 8.5: Pumpkin Carving 5

Here is an additional example to help you see different ways to use this pattern:

Topic : How to Carve a Pumpkin

Specific Purpose: To inform my audience how to carve a pumpkin.

Thesis: Carving a pumpkin with special techniques and tools can result in amazing creations.

Preview: First, I will explain the process of gutting the pumpkin in preparation for carving. Then, I will describe the way you use your special tools to carve the face you hope to create. Finally, I will show you a variety of different designs that are unique to make your pumpkin memorable.

I. First, let me explain exactly how you open up the pumpkin, remove the seeds, and clean it so it is ready to carve.

II. Second, let me describe how the tools you have on hand are used to draw and carve the face of the pumpkin.

III. Finally, let me show you several unique designs that will make your pumpkin dazzle your friends and neighbors.

Note that some instructors prefer their students not give “how-to” speeches. Always clear your topic with your instructor early on in the speech-writing process.

Spatial Pattern

A spatial pattern arranges ideas according to their physical or geographic relationships. Typically, we can begin with a starting point and look at the main points of your speech directionally from top to bottom, inside to outside, left to right, north to south, and so on. A spatial pattern allows for creativity as well as clarity. For example, a speech about an automobile could be arranged using a spatial pattern and you might describe the car from the front end to the back end or the interior to the exterior. A speech on Disneyland might begin with your starting point at the entrance on Main Street, and each subsequent main point may be organized by going through each land in the park in a directional manner. Even a speech on the horrific tsunami off the Indonesian coast of Sumatra on December 26, 2004, could be discussed spatially as you use the starting point and describe the destruction as it traveled, killing 250,000 people.

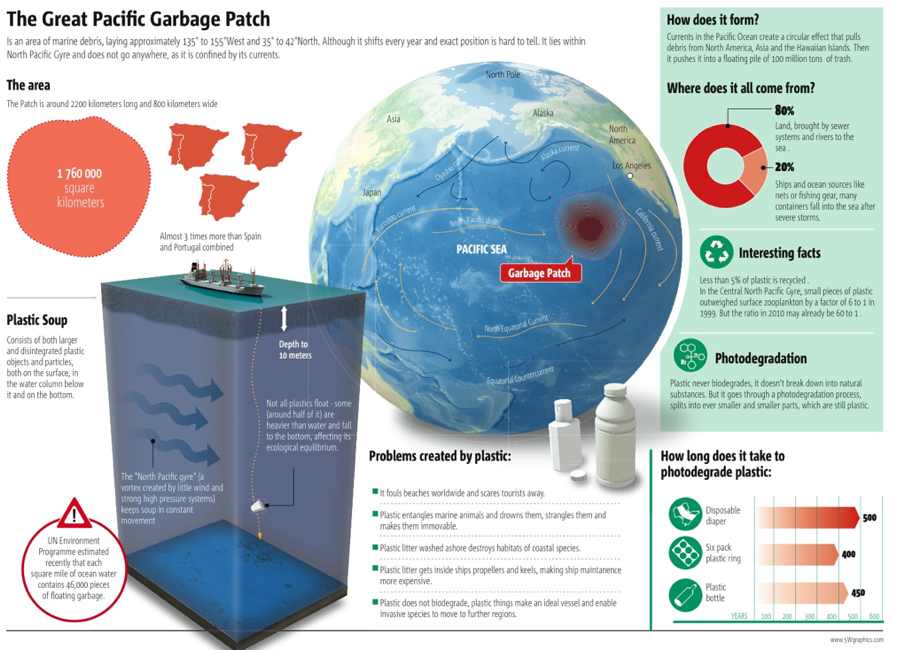

If you have never heard of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, it is marine debris that is in the North Pacific Ocean. Just like the tsunami in the previous example, this mass could likewise be discussed using a spatial pattern.

Figure 8.7: The Great Pacific Garbage Patch 7

In an informative speech, you could arrange your points spatially like this:

Topic: Great Pacific Garbage Patch

Thesis: The Great Pacific Garbage patch is not well known to most people; it consists of marine debris that is located in the North Pacific Ocean.

Preview: First, I will describe the Eastern Garbage Patch. Finally, I will explain the Western Patch.

I. The Eastern Garbage patch is located between the states of Hawaii and California.

II. The Western Garbage Patch is located near Japan.

Causal Pattern

A causal pattern of organization can be used to describe what occurred that caused something to happen, and what the effects were. Conversely, another approach is to begin with the effects and then talk about what caused them. For example, in 1994, there was a 6.7 magnitude earthquake that occurred in the San Fernando Valley in Northridge, California.

Figure 8.8: Northridge Meadows Apartment Building Collapse 8

Let’s look at how we can arrange this speech first by using a cause-effect pattern:

Topic: Northridge Earthquake

Thesis: The Northridge, California earthquake was a devastating event that was caused by an unknown fault and resulted in the loss of life and billions of dollars of damage.

I. The Northridge earthquake was caused by a fault that was previously unknown and located nine miles beneath Northridge.

II. The Northridge earthquake resulted in the loss of 57 lives and over 40 billion dollars of damage in Northridge and surrounding communities.

Depending on your topic, you may decide it is more impactful to start with the effects and work back to the causes ( effect-cause pattern ). Let’s take the same example and flip it around:

Thesis: The Northridge, California earthquake was a devastating event that resulted in the loss of life and billions of dollars in damage and was caused by an unknown fault below Northridge.

I. The Northridge earthquake resulted in the loss of 57 lives and over 40 billion dollars of damage in Northridge and surrounding communities.

II. The Northridge earthquake was caused by a fault that was previously unknown and located nine miles beneath Northridge.

Why might you decide to use an effect-cause approach rather than a cause-effect approach? In this particular example, the effects of the earthquake were truly horrible. If you heard all of that information first, you would be much more curious to hear about what caused such devastation. Sometimes natural disasters are not that exciting, even when they are horrible. Why? Unless they affect us directly, we may not have the same attachment to the topic. This is one example where an effect-cause approach may be very impactful.

One take-home idea for you about organizing patterns is that you can usually use any pattern with any topic. Could the Great Pacific Garbage Patch be explained using the chronological or causal patterns? Could the Northridge quake be discussed using the chronological or spatial patterns? Could a pumpkin-carving speech be spatially organized? The answer to all of the above is yes. The organizational pattern you select should be one that you think will best help the audience make sense of, and remember, your ideas.

Developing the Outline

Although students are often intimidated by the process of outlining a speech, you should know that it is a formulaic process. Once you understand the formula–the same one speech instructors have long taught and used to assess throughout the nation–speech writing should be a cinch. And remember, this process is what organizes your speech. A well-organized speech leads to better delivery. Simply, outlining is a method of organizing the introduction, body with main points, and conclusion of your speech. Outlines are NOT essays; they are properly formatted outlines! They use specific symbols in a specific order to help you break down your ideas in a clear way. There are two types of outlines: the preparation outline and the speaking outline.

Outline Types

When you begin the outlining process, you will create a preparation outline. A preparation outline consists of full, complete sentences, and thus, is void of awkward sentences and sentence fragments. In a full-sentence preparation outline, only one punctuated sentence should appear beside each symbol. In many cases, this type of outline will be used in preparing your speech, but will not be allowed to be used during your speech delivery. Remember that even though this outline requires complete sentences, it is still not an essay. The examples you saw earlier in this chapter were written in complete sentences, which is exactly what a preparation outline should look like.

A speaking outline is less detailed than the preparation outline and will include brief phrases or words that help you remember your key ideas. It is also called a “key word” outline because it is not written in complete sentences–only key words are present to jog your memory as needed. It should include elements of the introduction, body, and conclusion, as well as your transitions. Speaking outlines may be written on index cards to be used when you deliver your speech.

Confirm with your professor about specific submission requirements for preparation and speaking outlines.

Outline Components

Introduction and conclusion.

In Chapter 9, we identified the components of effective introductions and conclusions. Do you remember what they were? Your preparation outline should delineate the five elements of an introduction and the four elements of a conclusion . Recall, a complete introduction includes an attention-getter, relates the topic to the audience, establishes speaker credibility, states the thesis, and previews the main points. A quality conclusion will signal the speech is ending, restate the thesis, review the main points, and finish with a memorable ending.

Main Points

Main points are the main ideas in the speech. In other words, the main points are what your audience should remember from your talk, and they are phrased as single, declarative sentences. These are never phrased as a question, nor can they be a quote or form of citation. Any supporting material you have will be put in your outline as a subpoint. Since this is a public speaking class, your instructor will decide how long your speeches will be, but in general, you can assume that no speech will be longer than 10 minutes in length. Given that alone, we can make one assumption: All speeches will fall between 2 to 3 main points based simply on length. If you are working on an outline and you have ten main points, something is wrong, and you need to revisit your ideas to see how you need to reorganize your points.

All main points are preceded by Roman numerals (I, II, III, IV, V). Subpoints are preceded by capital letters (A, B, C, etc.), sub-sub points by Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, etc.), then sub-sub-sub points by lowercase letters (a, b, c, etc.). You may expand further than this. Here is a short template:

I. First main point

- First subpoint

- Second subpoint

- First sub-subpoint

- First sub-sub-subpoint

- Second sub-sub-subpoint

- Second main point

- Third main point

References List

A quality speech requires a speaker to cite evidence to support their claims. Your professor will likely require that you incorporate evidence from your research in both your outline and speech. In Chapter 7, we reviewed how to gather information, incorporate the research into your speech, and cite your sources, both in your written outline and during oral delivery. An ethical and credible speaker gives credit where credit is due and shares source information with the audience. Accordingly, the last piece of your preparation outline is the References List. The references list will include full written citations for all resources used in the composition and presentation of your speech. The structure of the references list follows a specific format dictated by the American Psychological Association 7th Ed. (remember, the Communication Studies discipline uses this APA formatting). Since formatting varies by source type, it is useful to refer to a reference guide to determine the exact citation formatting when writing your references list.

Written Oral Citations

There is a good chance your professor will ask you to include oral citations in your speech delivery. If so, you should include these in your preparation outline. The written oral citation is where you share your evidence and details of how you plan to cite the source during the delivery. Often, this is written in a similar format as “According to an article titled [title], written by [author] in [year], [resource content].” You should include enough source-identifying information for your audience to verify the accuracy and credibility of the content. In your outline, write out the specific source-information you will use to orally cite the source in your speech. Discuss the required number of oral citations with your professor and include all of them in your written outline. At FSW, we require three oral citations.

Outlining Principles

Next, we will cover the principles of outline which are outlining “rules” that you want to follow to be most effective. (Your English teachers will thank us, too!). First, read through this example outline for a main point about dogs. We will recall this example as we move through the principles. Don’t skip this example. Read it now!

Figure 6.9: Big and Small Dog 9

Topic: Dogs

Thesis: There are many types of dogs that individuals can select from before deciding which would make the best family pet.

Preview: First, I will describe the characteristics of large breed dogs, then I will discuss the characteristics of small breed dogs.

- Some large breed dogs need daily activity.

- Some large breed dogs are dog friendly.

- After eating is one of the times drooling is bad.

- The drooling is horrible after they drink, so beware!

- Great Pyrenees Mountain dogs drool as well.

- If you live in an apartment, these breeds could pose a problem.

Transition statement: Now that we’ve explored the characteristics of large breed dogs, let’s contrast this with small breeds.

- Some small breed dogs need daily activity.

- Some small breed dogs are dog friendly.

- They will jump on people.

- They will wag their tails and nuzzle.

- Beagles love strangers.

- Cockapoos also love strangers.

This dog example will help us showcase the following outlining principles.

Subordination and Coordination

The example above helps us to explain the concepts of subordination and coordination . Subordination is used in outline organization so the content is in a hierarchical order. This means that your outline shows subordination by indention. All of the points that are “beneath” (indented in the format) are called subordinate points. For example, if you have a job with a supervisor, you are subordinate to the supervisor. The supervisor is subordinate to the owner of the company. Your outline content works in a similar way. Using the dog example outlined in the previous section of this chapter, subpoints A, B, and C described characteristics of large breed dogs, and those points are all subordinate to main point I. Similarly, subpoints i and ii beneath subpoint C.1. both described dogs that drool, so those are subordinate to subpoint C. If we had discussed “food” under point C, you would know that something didn’t make sense! Overall, to check your outline for coherence, think of the outline as a staircase; walking down the outline one step at a time.

Tech tip: You can use the Ruler function of word processing software such as Microsoft Word or Google Docs to create tabs that align subordinated points with each other and keep the following lines of text properly aligned. If you only use the tab key, text that flows beyond the first line will usually not align with the proper tab stop for a given sub-point. Some instructors may provide you with a template, but experiment with the Ruler function on your own. It’s very useful!

You will also see that there is a coordination of points. Coordination is used in outline organization so that all of the numbers or letters represent the same idea. You know they coordinate because they align vertically and there is no diagonal relationship between the symbols. In the dog example, A, B, and C were all characteristics of large breed dogs, so those are all coordinated and represent the same “idea.” Had C been “German Shepherd,” then the outline would have been incorrect because that is a type of dog, not a characteristic, therefore, breaking the rules of subordination and coordination.

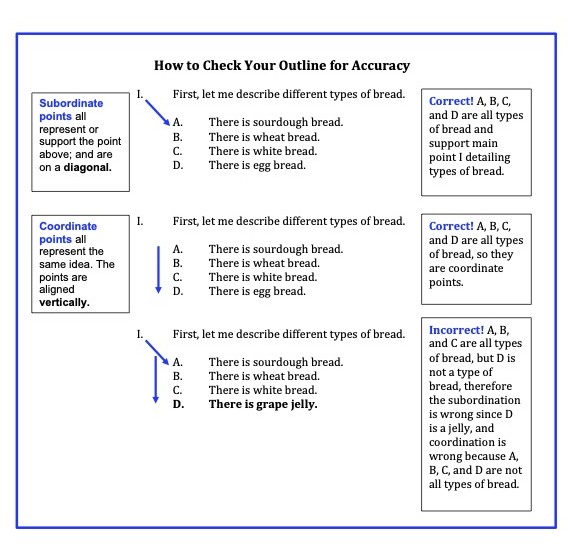

Figure 8.10 below provides you with a visual graphic of the subordination and coordination process. You will see that the topic of this very brief outline is bread. The main point tells you that there are different types of bread: sourdough, wheat, white, and egg.

To check this brief outline for subordination, you would look to see what subpoints fall beneath the main point. Do all of the sub-points represent a type of bread? You will see that they do! Next, to check for coordination, you would look at all of the subpoints that have a vertical relationship to each other. Are the subpoints these four types of bread? They are. The image also allows you to see what happens when you make a mistake. The third example shows the subpoints as sourdough, wheat, white, and jelly. Clearly, jelly is not a type of bread. Thus, there is a lack of both subordination and coordination in this short example. Make sure you spend some time checking the subordination and coordination of your own subpoints all the way throughout the outline until you have reached your last level of subordination. Now, study the image so that these principles of outlining are crystal clear; please ask your professor questions about this because it is a major part of speechmaking.

Figure 8.10: Checking Your Outline 10

You may be wondering why we bother with subordination and coordination. It actually helps both your listeners and your instructors. Listening is difficult. Any techniques that help audiences make sense of information are welcome. As soon as you begin talking, audiences listen for cues on how you are structuring information. If you organize clearly using logical relationships, your audience will be better able to follow your ideas. Further, for busy instructors examining many students’ outlines, when students’ grasp of subordination and coordination jump off the page due to their proper visual alignment, we know that students understand how to organize information for verbal delivery.

Parallelism

Another important rule in outlining is known as parallelism . This means that, when possible, you begin your sentences in a similar way, using a similar grammatical structure. For example, in the previous example on dogs, some of the sentences began with “some large breed dogs.” This type of structure adds clarity to your speech. Students often worry that parallelism will sound boring. It’s actually the opposite! It adds clarity. However, if you had ten sentences in a row, we would never recommend you begin them all the same way. That is where transitions come into the picture and break up any monotony that could occur.

The principle of division is an important part of outlining. Division is a principle of outlining that requires a balance between two subpoints in an outline. For each idea in your speech, you should have enough subordinate ideas to explain the point in detail and you must have enough meaningful information so that you can divide it into a minimum of two subpoints (A and B). If subpoint A has enough information that you can explain it, then it, too, should be able to be divided into two subpoints (1 and 2). So, in other words, division means this: If you have an A, then you need a B; if you have a 1, then you need a 2, and so on. What if you cannot divide the point? In a case like that, you would simply incorporate the information in the point above.

Connecting Your 2-3 Main Points

There are different types of transitions , which are words or phrases that help you connect all sections of your speech. To guarantee the flow of the speech, you will write transition statements to make connections between all sections of the outline. You will use these transitions throughout the outline, including between the introduction and the body, between the 2-3 main points, and between the body and the conclusion.

- Internal Reviews (Summaries) and Previews are short descriptions of what a speaker has said and will say that are delivered between main points.

Internal Reviews give your audience a cue that you have finished a main point and are moving on to the next main point. These also help remind the audience of what you have spoken about throughout your speech. For example, an internal review may sound like this, “So far, we have seen that the pencil has a long and interesting history. We also looked at the many uses the pencil has that you may not have known about previously.”

Internal Previews lay out what will occur next in your speech. They are longer than transitional words or signposts. For example, “Next, let us explore what types of pencils there are to pick from that will be best for your specific project.”

- Signposts are transitional words that are not full sentences, but connect ideas using words like “first,” “next,” “also,” “moreover,” etc. Signposts are used within the main point you are discussing, and they help the audience know when you are moving to a new idea.

- A nonverbal transition is a transition that does not use words. Rather, movement, such as pausing as you move from one point to another is one way to use a nonverbal transition. You can also use inflection by raising the pitch of your voice on a signpost to indicate that you are transitioning.

The most effective transitions typically combine many or all of the elements discussed here. Here is an example:

Now ( signpost ) that I have told you about the history of the pencil, as well as its many uses, ( internal review ) let’s look at what types of pencils you can pick from (mime picking up a pencil and moving a few steps for nonverbal transition ) that might be best for your project ( internal preview ).

Although this wasn’t the splashiest chapter in the text, it is one of the most critical chapters in speechmaking. Communicating your ideas in an organized and developed fashion means your audience will easily understand you. Each one of the principles and examples provided should be referenced as you work to develop your own speech. Remember that your speech will have a general purpose (typically to inform or persuade) and a specific purpose that details exactly what you hope to accomplish in the speech. Your speech’s thesis statement will be the central idea, what audiences most remember. The thesis is not just a list of main points, but it is a larger idea encompassing the two to three main points supporting it in the speech. Speeches should follow an organizational pattern, use standard formatting practices, and progress from full-sentence preparation outlines to key word speaking outlines before your performance. To see how all of these pieces come together, check out the sample preparation outline included at the bottom of the chapter. When writing your own preparation outline, use this sample as a guide. Consider each component a puzzle piece needed to make your outline complete.

Reflection Questions

- How has the information regarding general and specific purpose statements helped you to narrow your topic for your speech?

- Using brainstorming, can you generate a list of possible main points for your speech topic? Then, how will you decide which are the best choices to speak on?

- Which pattern(s) of organization do you think would be best for your informative speech? Why?

- Researchers say writing in small bursts is better. Do you agree that it is more effective to write your outline in small chunks of time rather than writing an entire speech in one day? Why or why not?

Body of the Speech

Coordination

General Purpose Statement

Internal Review (Summary)

Internal Preview

Nonverbal Transition

Preparation Outline

Preview Statement

Speaking Outline

Specific Purpose Statement

Subordination

Thesis Statement

Transitions

Written Oral Citation

Sample Speaking Outline

General Purpose: To inform

Specific Purpose: By the end of this speech, my audience will be able to explain bottle bricking, bottle brick benches, and their purposes.

Introduction —

I. Attention Getter: How many of you have thrown away a piece of plastic in the last 24 hours? Perhaps you pulled cellophane off a pack of gum or emptied out a produce bag. You probably don’t think about it, but those little pieces of plastic have two potential destinations – if they’re obedient, they go to a landfill. If they’re rogue, they can end up in waterways.

II. Thesis Statement: Today we will learn about a revolutionary way of dealing with plastic trash called bottle bricking.

III. Relevance Statement: As our planet’s ecological crises worsen, each of us should reflect on our impact on the environment. According to the Sea Education Society, a non-profit dedicated to reducing pollution through environmental education, there are more than one million pieces of plastic per square mile in the most polluted parts of the Atlantic Ocean, as Kirsten Silven of Earthtimes.org reported in (2011). If you want to take steps to preserve our world’s natural beauty for future generations, this speech is for you.

IV. Credibility Statement: When I first learned about bottle bricks I was incredulous. I thought “what is the point of stuffing plastic into plastic bottles?”. But soon the idea took hold of me and I was volunteering with local groups, eventually inspiring the creation of a Bottle Brick Bench at a high school I worked at.

V. Preview Main Points Statement: In this speech, we will learn how a bottle brick is made, how they are turned into benches, and the purpose behind this seemingly strange activity.

Transition: Before we go any further, let’s learn how to make a bottle brick.

Body —

- You will soon notice it everywhere.

- The trash must be clean and dry.

- Other hard-plastic bottles work, also.

- The bottles must be clean and dry.

- The stick should be long enough to reach the bottom of the bottle.

- Pick a smooth stick or give it a handle.

Transition: Now we know how to transform our trash into tools. But, what can bottle bricks be used for? One answer: a bench.

- Most creators argue you should use reclaimed stone (urbanite).

- Bricks make up the backrest.

- Cob is like mud.

- The benches make us realize how much plastic we toss, writes Brennan Blazer Bird on earthbench.org (2014) , home of the Peace on Earthbench Movement that the 25-year-old ecological educator founded.

- Later, people might think about it the plastic away they throw away

- Currently we have little use for soft plastic; most film plastics are not recyclable.

- Benches are a sign for change, and they are comfortable.

- Plastic “sequestered” in a bottle avoids landfills and the ocean.

- In landfills it gets into drinking water.

- All five subtropical ocean gyres have plastic “garbage patches,” according to 5gyres, a nonprofit dedicated to eliminating plastic pollution in the gyres (5gyres.org, 2014) .

- To have fun! The Harvest Collective called natural building such as earthbenches “incredibly fun and inspiring” on its website theharvestcollective.org (2014) .

Transition: So now that we understand why someone would make a bottle brick bench, let’s see if we’ve successfully “stuffed” this knowledge into our heads. [ I can make a bottle-stuffing motion to have fun during transition. ]

Conclusion —

- Signal end of the speech: I think it’s safe to say that every one of us throws away plastic on a regular basis has some degree of concern for the health of our planet.

- Review Main Points: Today we’ve learned how to make bottle bricks, how to put them into a bottle brick bench, and the reasons for doing so.

- Restate Thesis: Today we have seen that we can turn our seemingly useless, polluting trash into safe, useful technology. Maybe we can use such forward-thinking attitudes to promote sustainable cycles in all aspects of society.

- Specify desired audience response: I know that you aren’t all going to rush home and start bricking, but I’d like you to remember the basic premises underlying bottle bricks. But, by all means, if you’re interested in adding to the Peace on Earth Bench for Movement, visit earthbench.org or talk to me in class sometime.

- Strong closing (clincher): Who knows, maybe when you’re about to graduate you will be able to sit on a Bottle Brick Bench on campus reminding us all that we, through our individual choices, have the power to transform our species’ problems into solutions.

Introduction to Public Speaking Copyright © by Jamie C. Votraw, M.A.; Katharine O'Connor, Ph.D.; and William F. Kelvin, Ph.D.. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

7.4 Outlining Your Speech

Most speakers and audience members would agree that an organized speech is both easier to present as well as more persuasive. Public speaking teachers especially believe in the power of organizing your speech, which is why they encourage (and often require) that you create an outline for your speech. Outlines, or textual arrangements of all the various elements of a speech, are a very common way of organizing a speech before it is delivered. Most extemporaneous speakers keep their outlines with them during the speech as a way to ensure that they do not leave out any important elements and to keep them on track. Writing an outline is also important to the speechwriting process since doing so forces the speakers to think about the main ideas, known as main points, and subpoints, the examples they wish to include, and the ways in which these elements correspond to one another. In short, the outline functions both as an organization tool and as a reference for delivering a speech.

Outline Types

There are two types of outlines, the preparation outline and the speaking outline.

Preparation Outline

The first outline you will write is called the preparation outline . Also called a skeletal, working, practice, or rough outline, the preparation outline is used to work through the various components of your speech in an organized format. Stephen E. Lucas (2004) put it simply: “The preparation outline is just what its name implies—an outline that helps you prepare the speech.” When writing the preparation outline, you should focus on finalizing the specific purpose and thesis statement, logically ordering your main points, deciding where supporting material should be included, and refining the overall organizational pattern of your speech. As you write the preparation outline, you may find it necessary to rearrange your points or to add or subtract supporting material. You may also realize that some of your main points are sufficiently supported while others are lacking. The final draft of your preparation outline should include full sentences. In most cases, however, the preparation outline is reserved for planning purposes only and is translated into a speaking outline before you deliver the speech. Keep in mind though, even a full sentence outline is not an essay.

Speaking Outline