Disclaimer » Advertising

- HealthyChildren.org

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Description of the MUSP Cohort

Inclusion criteria for original research publications, quality of supporting literature, predictors: maltreatment types, ethical approval, prevalence and co-occurrence of maltreatment subtypes, cognition and education outcomes, psychological and mental health outcomes, addiction and substance use outcomes, sexual health outcomes, physical health, magnitude of effects, abuse, neglect, and cognitive development, psychological maltreatment: emotional abuse and/or neglect, sexual abuse, physical abuse, limitations, conclusions, long-term cognitive, psychological, and health outcomes associated with child abuse and neglect.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- CME Quiz Close Quiz

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Lane Strathearn , Michele Giannotti , Ryan Mills , Steve Kisely , Jake Najman , Amanuel Abajobir; Long-term Cognitive, Psychological, and Health Outcomes Associated With Child Abuse and Neglect. Pediatrics October 2020; 146 (4): e20200438. 10.1542/peds.2020-0438

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Video Abstract

Potential long-lasting adverse effects of child maltreatment have been widely reported, although little is known about the distinctive long-term impact of differing types of maltreatment. Our objective for this special article is to integrate findings from the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy, a longitudinal prenatal cohort study spanning 2 decades. We compare and contrast the associations of specific types of maltreatment with long-term cognitive, psychological, addiction, sexual health, and physical health outcomes assessed in up to 5200 offspring at 14 and/or 21 years of age. Overall, psychological maltreatment (emotional abuse and/or neglect) was associated with the greatest number of adverse outcomes in almost all areas of assessment. Sexual abuse was associated with early sexual debut and youth pregnancy, attention problems, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and depression, although associations were not specific for sexual abuse. Physical abuse was associated with externalizing behavior problems, delinquency, and drug abuse. Neglect, but not emotional abuse, was associated with having multiple sexual partners, cannabis abuse and/or dependence, and experiencing visual hallucinations. Emotional abuse, but not neglect, revealed increased odds for psychosis, injecting-drug use, experiencing harassment later in life, pregnancy miscarriage, and reporting asthma symptoms. Significant cognitive delays and educational failure were seen for both abuse and neglect during adolescence and adulthood. In conclusion, child maltreatment, particularly emotional abuse and neglect, is associated with a wide range of long-term adverse health and developmental outcomes. A renewed focus on prevention and early intervention strategies, especially related to psychological maltreatment, will be required to address these challenges in the future.

Child maltreatment is a major public health issue worldwide, with serious and often debilitating long-term consequences for psychosocial development as well as physical and mental health. 1 In the United States alone, 3.5 million children are reported for suspected maltreatment each year, with an annual substantiated maltreatment rate of 9.1 per 1000 children. 2 Some of the long-term adverse outcomes associated with maltreatment include cognitive disability, anxiety and depression, psychosis, teen-aged pregnancy, addiction disorders, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. 3 Understanding the distinctive impact of differing types of maltreatment may help medical professionals provide more wholistic care and treatment recommendations as well as identify more specific public health targets for primary prevention.

Unfortunately, however, little is known about the long-term effects of differing types of child maltreatment, which include sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect. 4 According to a meta-analysis review, 5 research on child maltreatment has predominantly been focused on sexual abuse, with far less attention paid to psychological maltreatment (emotional abuse and/or neglect) and the co-occurrence of different types of maltreatment. In addition, most of the current evidence is derived from cross-sectional studies, which may be subject to recall bias, 6 – 8 in which an outcome status (such as depression) may influence recall of the exposure (ie, previous maltreatment). Few previous studies have adequately controlled for confounding variables, such as perinatal risk, socioeconomic adversity, parental psychopathology, and impaired early childhood development, which may predispose to both child maltreatment and later adverse health outcomes.

Longitudinal studies offer evidence that is more robust, but these studies are relatively few in number and have generally been limited to certain sociodemographic groups 9 or to specific types of child maltreatment, such as sexual abuse. 1 , 10 Other longitudinal studies have relied on retrospective recall of maltreatment rather than prospectively collected agency-reported data. 11 – 13 In studies in which prospective data have been collected, 7 , 13 – 17 only a few have compared different types of child maltreatment. 7 , 16 , 17

In this special article, we review findings from the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy (MUSP), a now 40-year longitudinal prenatal cohort study from Brisbane, Australia, involving >7000 women and their children. 18 Unique features of the MUSP include its use of a population-based sample, its use of prospectively substantiated child maltreatment reports, and its consideration of different subtypes of maltreatment. In addition, the study design controlled for a wide range of confounders and covariates, including both maternal and child sociodemographic and mental health variables. This combined body of work, which includes numerous publications over the past decade, has documented a broad range of adverse outcomes associated with child maltreatment, including deficits in cognitive and educational outcomes 19 – 21 ; mental health problems, such as anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), psychosis, delinquency, and intimate partner violence (IPV) 22 – 25 ; substance abuse and addiction 26 – 30 ; sexual health problems 31 ; physical growth and health deficits 32 – 35 ; and overall decreased quality of life. 36

Our purpose for this special article is to compare the effects of 4 differing types of maltreatment on long-term cognitive, psychological, addiction, and health outcomes assessed in the offspring at ∼14 and/or 21 years of age. Rather than providing a systematic review or meta-analysis of the current literature, which would include diverse study designs and purposes, we report and compare the findings of individual articles that used a common data set and standard methodology to study a broad array of outcomes. We particularly highlight the long-term impact of emotional abuse and neglect, which has received far less attention in the literature.

Between 1981 and 1983, 8556 consecutive pregnant women who attended their first prenatal clinic visit at the Mater Mothers’ Hospital in Brisbane, Australia, agreed to participate ( Fig 1 ). After excluding mothers who did not deliver a singleton infant at the Mater Mothers’ Hospital or withdrew consent, the MUSP birth cohort consisted of 7223 mother-infant dyads, who were followed over 2 decades: at 3 to 5 days, 6 months, 5 years, 14 years and 21 years. Midway through the study, this rich data set was anonymously linked to state reports of child abuse and neglect, which identified some form of suspected maltreatment in >10% of cases. 37 Notified cases, which had been referred from the community or by general medical practitioners, were investigated by the Queensland government child protection agency. Substantiated maltreatment was determined after a formal investigation when there was “reasonable cause to believe that the child had been, was being, or was likely to be abused or neglected.” 38 Substantiated maltreatment occurred when a notified case was confirmed for (1) sexual abuse, “exposing a child to or involving a child in inappropriate sexual activities”; (2) physical abuse, “any non-accidental physical injury inflicted by a person who had care of the child”; (3) emotional abuse, “any act resulting in a child suffering any kind of emotional deprivation or trauma”; or (4) neglect, “failure to provide conditions that were essential for the healthy physical and emotional development of a child,” which encompassed physical, emotional and medical neglect. 37

Overview of the MUSP enrollment and testing.

We searched PubMed from inception to April 2020 for published MUSP articles in which agency-reported child maltreatment was evaluated as the predictor of a range of outcomes. Studies needed to meet the following criteria for inclusion in the review: (1) notified or substantiated abuse and neglect was listed as a main predictor variable and (2) outcomes included standardized measurements of cognitive, psychological, behavioral, or health functioning. From ∼340 published MUSP studies, we identified 24 articles dealing with child maltreatment, of which 21 included state-reported maltreatment versus self-reported maltreatment data ( n = 3). Nineteen of the 21 articles met all inclusion criteria and were evaluated in this review ( Fig 2 ). One study was excluded because it only examined outcomes associated with sexual abuse. 8 Another article was excluded because its outcome measures were similar to another included study. 29

![conclusions from research on child maltreatment have found that FIGURE 2. Published studies from the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy, linking long-term outcomes with specific maltreatment subtypes (adjusted coefficients or odds ratios ± 95% confidence intervals). CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale; CI, confidence interval; N, number of offspring in sample; N(Mal), number of offspring who experienced maltreatment. aIn different articles adjusting for co-occurrence of maltreatment subtypes was handled in different ways: (1) statistical adjustment: each maltreatment subtype predictor was statistically adjusted for the other maltreatment subtypes (eg, neglect was adjusted for the occurrence of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse) and is reflected in the table’s odds ratios and coefficients; (2) exclusive categories: different combinations of maltreatment types are included in mutually exclusive groups (eg, physical abuse only, physical abuse and emotional abuse only, physical and emotional abuse and neglect [without sexual abuse], etc; see Table 1); (3) nonexclusive categories: maltreatment categories may overlap with other categories (eg, any substantiated abuse [sexual, physical, or emotional] versus any substantiated neglect); and (4) none: no statistical adjustments or combined categories were presented for co-occurring maltreatment subtypes. bAdjusted coefficients (95% CI) were reported as statistical association measures rather than adjusted odds ratios. cCases of notified (rather than substantiated) maltreatment. In the study by Mills et al,26 a sensitivity analysis was performed after exclusion of unsubstantiated cases of maltreatment. The associations between any maltreatment and substance use were similar to those seen in the original analysis after full adjustment. dMedium effect size, based on magnitude of the adjusted odds ratio (2 ≤ odds ratio ≤ 4). eLarge effect size, based on magnitude of the adjusted odds ratio (odds ratio > 4).](https://aap2.silverchair-cdn.com/aap2/content_public/journal/pediatrics/146/4/10.1542_peds.2020-0438/4/m_peds_20200438_f2.jpeg?Expires=1718985662&Signature=AQBgIhNVUiXKYEEe-5Kii0icczWe7Z52EwtXWEUBZ0dR~2pXrgRn6bep32sNK5o9OcP0k1ubklOMGSSlRCmeBiKQQPqu~JphGsv33xGYXelayh4znf3q7Hkdm7nBX~WmpAAdNzCKVvCUu0OumJSzn8LKp5CQc8~Aaq-gRu19KBMZujr3q8dgMQ0gdngTcsHKhgOrVlEq6Bc21DcmxBu59vDJA8dshBgOujELGJYXiK17Z-4YJVTgmh4-CSgKKOv-jQA6uOSRSN~ADIlTb4g21RRsZxZ2Mf0AovyWHOIHRZDzfFDaS2MONneTr~oBUnmYg0QNM0N35Smo6jBnTutoPw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Published studies from the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy, linking long-term outcomes with specific maltreatment subtypes (adjusted coefficients or odds ratios ± 95% confidence intervals). CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale; CI, confidence interval; N , number of offspring in sample; N (Mal) , number of offspring who experienced maltreatment. a In different articles adjusting for co-occurrence of maltreatment subtypes was handled in different ways: (1) statistical adjustment: each maltreatment subtype predictor was statistically adjusted for the other maltreatment subtypes (eg, neglect was adjusted for the occurrence of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse) and is reflected in the table’s odds ratios and coefficients; (2) exclusive categories: different combinations of maltreatment types are included in mutually exclusive groups (eg, physical abuse only, physical abuse and emotional abuse only, physical and emotional abuse and neglect [without sexual abuse], etc; see Table 1 ); (3) nonexclusive categories: maltreatment categories may overlap with other categories (eg, any substantiated abuse [sexual, physical, or emotional] versus any substantiated neglect); and (4) none: no statistical adjustments or combined categories were presented for co-occurring maltreatment subtypes. b Adjusted coefficients (95% CI) were reported as statistical association measures rather than adjusted odds ratios. c Cases of notified (rather than substantiated) maltreatment. In the study by Mills et al, 26 a sensitivity analysis was performed after exclusion of unsubstantiated cases of maltreatment. The associations between any maltreatment and substance use were similar to those seen in the original analysis after full adjustment. d Medium effect size, based on magnitude of the adjusted odds ratio (2 ≤ odds ratio ≤ 4). e Large effect size, based on magnitude of the adjusted odds ratio (odds ratio > 4).

Each of the reviewed articles followed Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for the conduct of cohort studies. 41 The quality of the studies was also evaluated by using a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, which is used to assess the following domains: sample representativeness and size, comparability between respondents and nonrespondents, ascertainment of outcomes, and statistical quality. 42 On the basis of this assessment, all of the MUSP studies were determined to be of low risk of bias, with a score of 4 out of 5 points ( Supplemental Information ).

In all but 2 studies (which used notified maltreatment 21 , 26 ) events were dichotomized and coded as substantiated maltreatment versus no substantiated maltreatment. According to a validated classification of maltreatment types, 43 specific categories and co-occurring forms of childhood maltreatment 44 were used to predict outcomes. In 2 studies, 19 , 20 all types of abuse were combined into 1 category and compared to neglect, whereas in another study, sexual abuse was compared to any combination of nonsexual maltreatment. 21 In 2 other studies, 26 , 40 emotional abuse and neglect (examples of psychological maltreatment) were combined, partly because of overlapping definitional constructs from the government child protection agency (emotional abuse included “emotional deprivation,” and neglect included the failure to provide for “healthy…emotional development”). In all but 2 of the included articles, 25 , 33 co-occurrence of different types of maltreatment was considered, either by examining specific combinations of maltreatment types (in exclusive or nonexclusive overlapping categories) or by statistically adjusting for all remaining types of maltreatment ( Fig 2 ).

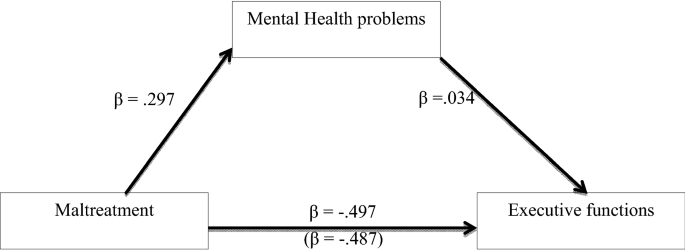

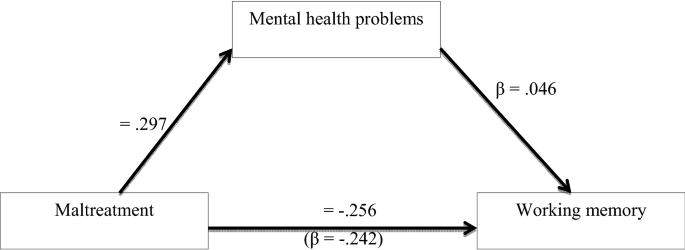

All of the odds ratios, mean differences, or coefficients were adjusted for potential confounding variables ( Fig 3 ). All articles adjusted for a variety of sociodemographic variables, such as age, race, education, income, and marital status. Perinatal and/or childhood factors, such as birth weight, gestational age, and breastfeeding status, were used as covariates, particularly in articles in which cognitive and educational outcomes were examined. Psychological and mental health variables (such as internalizing and externalizing behavior problems, maternal depression, chronic stress, or exposure to violence) were primarily included as covariates in mental health outcome studies, especially for psychosis. Addiction studies adjusted for youth and maternal alcohol or tobacco use, among other covariates, and physical health outcome studies adjusted for relevant covariates (such as BMI in a study of dietary fat intake and parental height when studying offspring height). In selected articles, maltreatment subtypes were also statistically adjusted for the other types of maltreatment to determine independent effects.

Covariates used in published articles from the MUSP to adjust for possible confounding. a Race: child’s race, parental race, and maternal or paternal racial origin at pregnancy. b Child age: child age and gestational age. c Maternal age: maternal age at the first visit clinic or at pregnancy. d Maternal education: maternal education (prenatal or at birth). e Family income: annual family income, familial income over the first 5 years or family poverty before birth or over the first 5 years of life, family income before birth, and annual family income. f Maternal marital status and social support: same partner at birth and 14 years and social support at 5 years. g Maternal depression: maternal depression during pregnancy, 3- to 6-month follow-up, or 21-year follow-up; chronic maternal depression. h Maternal alcohol use: maternal alcohol use at 3- to 6-month or 14-year follow-up and binge drinking. i Maternal cigarette use: cigarette use during pregnancy, 6 months postpartum, or at 14-year follow-up. ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale; IPV, intimate partner violence. Covariates used in published articles from the MUSP to adjust for possible confounding.

A total of 46 outcomes were assessed at 14 years ( n = 5200) and/or 21 years ( n = 3778) ( Fig 1 ) and were grouped into 5 domains ( Fig 2 ):

Cognition and education outcomes included reading ability and perceptual reasoning measured in adolescence, and, at age 21, receptive verbal intelligence and failure to complete high school or be either enrolled in school or employed; attention problems were measured at both time points.

Psychological and mental health outcomes at 21 years included internalizing and externalizing behavior problems (which were also assessed at 14 years), lifetime anxiety disorder, depressive disorder and symptoms, PTSD, lifetime psychosis diagnosis, psychotic symptoms (such as delusional experience or visual and/or auditory hallucinations), delinquency, experience of IPV or harassment, and overall quality of life.

Addiction and substance use, measured at both time points, included alcohol and cigarette use at 14 and 21 years, and cannabis abuse and/or dependence (including early onset) and injecting-drug use at the 21-year follow-up.

Sexual health was investigated at age 21 in terms of early initiation of sexual experience, having multiple sexual partners, youth pregnancy, and miscarriage or termination.

Physical health outcomes measured at 21 years included symptoms of asthma, high dietary fat intake, poor sleep quality, and height deficits.

The 14-year assessments included a youth questionnaire ( n = 5172) and in-person cognitive testing ( n = 3796). The 21-year visit included an in-person assessment of mental health diagnoses in a subset of the cohort ( n = 2531) with the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), which is based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition criteria 45 ( Fig 1 ). All of the questionnaire and interview measures were validated, except for reported frequencies of specific events (ie, pregnancy, number of cigarettes, etc).

Associations were described by using either adjusted odds ratios or mean differences and coefficients, along with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals, and were plotted to visualize and compare the statistical significance of each association across specific outcome categories and types of maltreatment ( Figs 4 – 8 ).

Child maltreatment and cognition and educational outcomes at 14 and 21 years. A, Adjusted coefficients ± 95% confidence intervals. B, Odds ratios ± 95% confidence intervals. * P < .05.

Child maltreatment and psychological and mental health outcomes at 14 and 21 years. A, Adjusted coefficients ± 95% confidence intervals. B, Odds ratios ± 95% confidence intervals. * P < .05.

Child maltreatment and addiction and substance use outcomes at 14 and 21 years (adjusted odds ratio ± 95% confidence interval). * P < .05.

Child maltreatment and sexual health outcomes at 21 years (adjusted odds ratio ± 95% confidence interval). * P < .05.

Child maltreatment and physical health outcomes at 21 years. A, Adjusted odds ratio ± 95% confidence interval. B, Adjusted coefficients ± 95% confidence interval. * P < .05.

The MUSP was approved by the Human Ethics Review Committee of The University of Queensland and the Mater Misericordiae Children’s Hospital. Ethical approval was obtained separately from the Human Ethics Review Committee of The University of Queensland for linking substantiated child maltreatment data to the 21-year follow-up data.

In this cohort of 7214 children ( Fig 1 ), 7.1% ( n = 511 children) experienced at least 1 episode of substantiated maltreatment. Substantiated sexual abuse was reported in 2.0% ( n = 147), physical abuse in 4.0% ( n = 287), emotional abuse in 3.7% ( n = 267), and neglect in 3.7% of cases ( n = 269) ( Table 1 ). Almost 60% of the children with substantiated maltreatment had multiple substantiated episodes (293 children; range: 2–14 episodes per child; median: 3 episodes per child 37 ). Of the 3778 young adults included in the 21-year follow-up, 4.5% ( n = 171) had a history of substantiated maltreatment, 39 including sexual abuse ( n = 53), physical abuse ( n = 60), emotional abuse ( n = 71), and neglect ( n = 89).

More than half of the children who experienced substantiated maltreatment were reported for ≥2 co-occurring maltreatment types ( Table 1 ). Of the substantiated sexual abuse cases, 57.1% of the children experienced ≥1 additional maltreatment types (84 of 147); for physical abuse, this proportion was 79.1% (227 of 287); for emotional abuse, 83.5% (223 of 267); and for neglect, 73.6% (198 of 269). In particular, emotional abuse and neglect co-occurred, with or without other types of maltreatment, in ∼59% of cases. 46

Nonexclusive and Exclusive Categorization of Child Maltreatment Subtypes (Single and in Combination) Within the MUSP Cohort

Abuse (a combined category) and neglect were both associated with significantly lower cognitive scores at both 14 and 21 years, as well as with negative long-term educational and employment outcomes in young adulthood. 19 , 20 This was after adjusting for factors such as the child’s race, sex, birth weight, breastfeeding exposure, and age; family income; and maternal education and alcohol and/or tobacco use ( Fig 3 ). Specifically, proxy measures of IQ, such as reading ability and perceptual reasoning, at age 14 years were adversely associated with both substantiated abuse and neglect. 19 Sexual abuse was associated with attention problems in adolescence, whereas nonsexual maltreatment was associated with attention problems at both time points. 21 Young adults who experienced substantiated child maltreatment had reduced scores on the Peabody Vocabulary Test at 21 years. In terms of educational outcomes in young adulthood, both abuse and neglect manifested a threefold to fourfold increase in odds of failing to complete high school and a twofold to threefold increase in the likelihood of being unemployed at age 21 years 20 ( Figs 2 and 4 ).

During adolescence, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect were all significantly associated with both internalizing and externalizing behavior problems, although this was not the case for physical abuse notifications without co-occurring emotional abuse or neglect. 22 After adjustment for relevant sociodemographic variables, the associations with emotional abuse and neglect remained significant at 21 years. 39 No statistically significant association was found between sexual abuse and these behavior problems at either time point.

Psychological maltreatment in childhood was associated with all of the other 15 psychological and mental health outcomes in young adulthood, except for delinquency in women. This was true after adjustment for sociodemographic variables and psychological and mental health problems (such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, aggressive behavior problems, and maternal depression or adverse life events, in the case of psychosis and/or IPV exposure outcomes) ( Fig 3 ). Specifically, both emotional abuse and neglect were significantly associated at 21 years with all of the following outcomes: anxiety, depression, PTSD, psychosis (with some exceptions), delinquency in men, and experiencing IPV and harassment (except for neglect). 22 – 25 , 39 Emotional abuse and neglect were the only maltreatment subtypes associated with a significant decrease in quality-of-life scores. 36

The only mental health outcomes associated with sexual abuse were clinical depression, lifetime PTSD, and experiencing physical IPV. 8 , 25 , 39 Physical abuse was associated with externalizing behavior problems and delinquency (in men), internalizing behavior problems and depressive symptoms, experience of IPV, and PTSD 22 , 24 , 25 , 39 ( Figs 2 and 5 ).

Overall, emotional abuse and/or neglect were associated with all categories of substance use and addiction at both 14 and 21 years, whereas physical and sexual abuse were associated with surprisingly few substance abuse outcomes. Specifically, childhood emotional abuse and neglect were associated with adolescent substance use at age 14, including alcohol use and smoking. 26 This was after adjustment for sociodemographic factors and youth and maternal drug use. The association with cigarette and alcohol use persisted from adolescence to adulthood. The category of "any cigarette use" was the only addiction outcome associated with all 4 types of maltreatment. 40 At 21 years, emotional abuse and neglect were both associated with the early onset of cannabis abuse after adjustment for maternal stress and cigarette use. Additionally, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect all revealed increased odds of cannabis dependence at age 21, with early onset associated with physical abuse and neglect. 28 In contrast, only emotional abuse significantly predicted injecting-drug use in young adult men, after adjustment for maternal alcohol use and depression, whereas all types of substantiated childhood maltreatment were associated with injecting-drug use in women. 27 Sexual abuse was not associated with any addiction or substance use outcome except for cigarette use at 21 years ( Figs 2 and 6 ).

All forms of maltreatment were significantly associated, at 21 years, with early onset of sexual activity and subsequent youth pregnancy. This was after adjustment for factors such as gestational age, youth psychopathology, and drug use. Neglect was the only type of maltreatment associated with having multiple sexual partners and was the maltreatment type most strongly associated with most other sexual health outcomes, especially youth pregnancy. Pregnancy miscarriage was modestly associated with emotional abuse, whereas termination of pregnancy was not associated with any maltreatment subtype 31 ( Figs 2 and 7 ).

Reduced adult height at 21 years, adjusted for parental height, was associated with all maltreatment subtypes except sexual abuse (which was not associated with any of the physical health outcomes). At 21 years, physical abuse was also associated with high dietary fat intake, a risk factor for obesity (adjusted for BMI), and poor sleep quality in men (adjusted for psychopathology and drug use). Asthma at 21 years revealed a modest association with emotional abuse. The combined category of any maltreatment was also associated with high dietary fat intake ( Figs 2 and 8 ).

To estimate the magnitude of potential effects of child maltreatment on long-term outcomes, other studies have used a number of statistical techniques. In one Australian study that used the MUSP and other data sets, the population attributable risk of child maltreatment causing anxiety disorders in men and women, was estimated to be 21% and 31%, respectively, and 16% and 23% for depressive disorders. 46 Similarly, in the MUSP study on cognitive and educational outcomes of maltreated youth, the population attributable risk of child maltreatment leading to “failure to complete high school” was 13%, and 14% for “failure to be in either education or employment at 21 years.” 20

Based on one published metric of effect size using the magnitude of the adjusted odds ratio, 47 77% of the statistically significant associations in this review were considered to have a medium to large effect size (odds ratio ≥2), including 10% with a large effect size (odds ratio >4) ( Fig 2 ).

In summary, over the past decade, the MUSP has revealed that child maltreatment is associated with a broad array of adverse outcomes during adolescence and young adulthood, including the following:

deficits in cognitive development, attention, educational attainment, and employment;

serious mental health problems, including anxiety, depression, PTSD, and psychosis, as well as delinquency and the experience of IPV;

substance use and addiction problems;

sexual health problems; and

physical health limitations and risk.

These results were seen after adjustment for a broad range of relevant sociodemographic, perinatal, psychological, and other risk factors ( Fig 3 ). Many of the studies also adjusted for the other subtypes of child maltreatment and demonstrated that specific maltreatment types were closely associated with particular outcomes.

Significant cognitive delays and educational failure were seen for both abuse and neglect across adolescence and adulthood. In another study, the authors concluded that preexisting cognitive impairments at 3 or 5 years may explain this association, rather than maltreatment per se. 16 However, other research has revealed that children neglected over the first 4 years of life show a progressive decline in cognitive functioning, which is associated with a significantly reduced head circumference at 2 and 4 years of age. 48 In rodent models, contingent maternal behavior is linked with infant cognitive development, and possible mechanisms include increases in synaptic connections within the hippocampus 49 and reduced apoptotic cell loss. 50 Prolonged maternal separation, in contrast, is associated with impaired cognitive development in rodent and primate models. 51 , 52

One of the most striking conclusions from this review was the broad association between emotional abuse and/or neglect and adverse outcomes in almost all areas of assessment ( Fig 2 ). In stark contrast, physical abuse and sexual abuse were associated with far fewer adverse outcomes. Overall, quality of life was lower for those who had experienced emotional abuse and neglect but not for those who had experienced physical or sexual abuse. Although emotional abuse and neglect often co-occur with other types of maltreatment, 46 the associated outcomes were generally robust even after statistical adjustment or separation into differing maltreatment categories ( Fig 2 ).

Emotional abuse and neglect in early childhood may lead to psychopathology via insecure attachment, 53 , 54 which has been associated with externalizing behavior problems 55 and impaired social competence. 56 , 57 Emotional neglect, in particular, may lead to deficits in emotion recognition and regulation, as well as insensitivity to reward, 3 potentially influencing social and emotional development. Neglected children are less able to discriminate facial expressions and emotions, 58 whereas youth who have been emotionally neglected show blunted development of the brain’s reward area, the ventral striatum. 59 Reduced reward activation may predict risk for depression, 59 addiction, 60 and other psychopathologies. 61

Neglect was also associated with the early onset of sexual activity, multiple sexual partners, and youth pregnancy, even after adjustment for other maltreatment subtypes. This suggests that neglect may result in compensatory efforts to obtain sexual intimacy, consistent with other studies revealing higher rates of unprotected sex 62 and adolescent pregnancy in neglected children. 63 In the animal literature, female rodents that experience maternal deprivation tend to have an earlier onset of puberty and increased sexual receptivity, leading to elevated reproductive activity to help offset an environment of higher offspring risk. 64 , 65

As observed elsewhere, 66 sexual abuse was associated with early sexual experimentation and youth pregnancy as well as symptoms of PTSD and depression. Risky sexual behaviors were independent of other types of maltreatment but were not specific for sexual abuse. An additional MUSP study comparing self-reported and agency-notified child sexual abuse revealed consistent associations with major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, and PTSD. 8 The absence of associations with other adverse outcomes, however, may be, in part, due to the lower prevalence of substantiated sexual abuse, especially at the 21-year follow-up.

Outcomes associated with physical abuse differed from those associated with sexual abuse, with increased odds of externalizing behavior problems, and delinquency in men. Jaffee 3 suggests that physical abuse, in particular, may lead to a hypervigilance response to threat, including negative attentional bias, disproportionate to relatively mild threat cues. Studies have revealed that physically abused children show selective attention to anger cues, 67 have difficulty disengaging from them, 58 , 68 and are more likely to misinterpret facial cues as being angry or fearful. 69

Although these studies demonstrated significant associations between maltreatment and a range of long-term outcomes, association does not equal causality. The causal mechanisms proposed above are tentative and may relate to multiple types of maltreatment.

Other limitations should also be considered. Firstly, selective attrition of socioeconomically disadvantaged and maltreated young people was evident in the MUSP cohort ( Supplemental Information ). However, based on multiple imputation calculations and inverse probability weighting of MUSP data, 18 , 70 differences in the rate of loss to follow-up, for both dependent and independent variables, made little difference to either the estimates or their precision, mirroring findings from other longitudinal studies. 71 In addition, the findings were mostly unchanged when using propensity analysis, which is used to assess the effects of nonrandom sampling variation by analyzing the probability of assignment to a particular category within an observational study given the observed covariates. 72 Specifically, the sample was weighted so that it better resembled sociodemographic characteristics at baseline to minimize bias from differential attrition in those with greater socioeconomic disadvantage.

Secondly, differences in the prevalence of specific maltreatment subtypes might have influenced the statistical power to detect true effects, particularly regarding sexual abuse ( Table 1 ).

Finally, the co-occurrence of different types of maltreatment may have impacted the ability to accurately predict the associations between specific types of maltreatment and outcomes. Other studies have revealed that emotional abuse and neglect, in particular, are more likely to co-occur with each other and with other types of maltreatment. 73 However, even in those articles that statistically adjusted for other co-occurring maltreatment subtypes, the associated outcomes linked with emotional abuse and/or neglect were generally robust. In articles that did not adjust for these co-occurrences, some of the strongest associations were still observed for emotional abuse and/or neglect.

Child maltreatment, particularly psychological maltreatment, is associated with a broad range of negative long-term health and developmental outcomes extending into adolescence and young adulthood. Although these data do not establish causality, neurodevelopmental pathways are likely influenced by stress and early social experience through epigenetic mechanisms, which may affect gene expression and regulation and, ultimately, behavior and development. 3 , 74

Understanding the developmental roots of these adverse outcomes may motivate physicians to more systematically inquire about early-life trauma and refer patients to more appropriate treatment services. 75 , 76 Even more importantly, early intervention and prevention programs, such as prenatal and infancy nurse home visiting, 77 have demonstrated, in randomized clinical trials, diminished rates of child abuse and neglect. 78 , 79 Long-term benefits to the offspring include decreased childhood internalizing problems, 80 reduced antisocial behavior and substance abuse in adolescence, 81 and improved cognitive skills extending into young adulthood. 80 , 82 Supporting at-risk parents and young children should thus be an urgent priority.

Dr Strathearn conceptualized and designed the original study linking the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy data set with substantiated reports of child maltreatment, drafted the special article, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Giannotti assisted in drafting the manuscript and prepared all tables and figures; Drs Mills, Kisely, and Abajobir conceptualized and wrote the original research articles summarized in this article; Dr Najman was the original principal investigator of the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy; and all authors critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FUNDING: Partially supported by the US National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA026437). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of this institute or the National Institutes of Health. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Composite International Diagnostic Interview

intimate partner violence

Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy

posttraumatic stress disorder

Competing Interests

Supplementary data.

Advertising Disclaimer »

Citing articles via

Email alerts.

Affiliations

- Editorial Board

- Editorial Policies

- Journal Blogs

- Pediatrics On Call

- Online ISSN 1098-4275

- Print ISSN 0031-4005

- Pediatrics Open Science

- Hospital Pediatrics

- Pediatrics in Review

- AAP Grand Rounds

- Latest News

- Pediatric Care Online

- Red Book Online

- Pediatric Patient Education

- AAP Toolkits

- AAP Pediatric Coding Newsletter

First 1,000 Days Knowledge Center

Institutions/librarians, group practices, licensing/permissions, integrations, advertising.

- Privacy Statement | Accessibility Statement | Terms of Use | Support Center | Contact Us

- © Copyright American Academy of Pediatrics

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Preventing child maltreatment: Key conclusions from a systematic literature review of prevention programs for practitioners

Affiliations.

- 1 Bob Shapell School of Social Work, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv, 69978, Israel. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Bob Shapell School of Social Work, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv, 69978, Israel.

- PMID: 34087537

- DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105138

Child maltreatment (CM) is a worldwide social problem and there is a large consensus that its prevention is of crucial importance. The current literature review highlights CM prevention studies that target practitioners, with the aim of assessing the knowledge in this area, informing future efforts and benefiting the international task of mitigating CM. Specifically, the study presents key conclusions from prevention programs evaluated in peer-reviewed journals from the last decade selected using the PRISMA systematic literature review guidelines. Out of the 26 manuscripts that discussed prevention programs targeted at practitioners, 20 programs were identified. While sexual abuse prevention programs were the most common, followed by programs addressing general child maltreatment, only two studies addressed child physical abuse. More than a third of the prevention programs were interdisciplinary, while healthcare providers had the highest number of specifically tailored programs. The discussion addresses the considerable lack of detail in the relevant manuscripts and urges future efforts to further elaborate on necessary details to enable other researchers and practitioners to better assess and determine the congruence between child maltreatment research and prevention programs. Additionally, some methodological issues in the included manuscripts, such as the lack of control groups and the related challenges, are discussed.

Keywords: Child maltreatment (CM); Education; PRISMA; Prevention; Systematic literature review; Welfare.

Copyright © 2021 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Systematic Review

- Child Abuse* / prevention & control

- Physical Abuse

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Systematic Review

- Published: 25 September 2020

Social determinants of health and child maltreatment: a systematic review

- Amy A. Hunter 1 , 2 , 3 &

- Glenn Flores 3 , 4

Pediatric Research volume 89 , pages 269–274 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

7992 Accesses

53 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

Child maltreatment causes substantial numbers of injuries and deaths, but not enough is known about social determinants of health (SDH) as risk factors. The aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the association of SDH with child maltreatment.

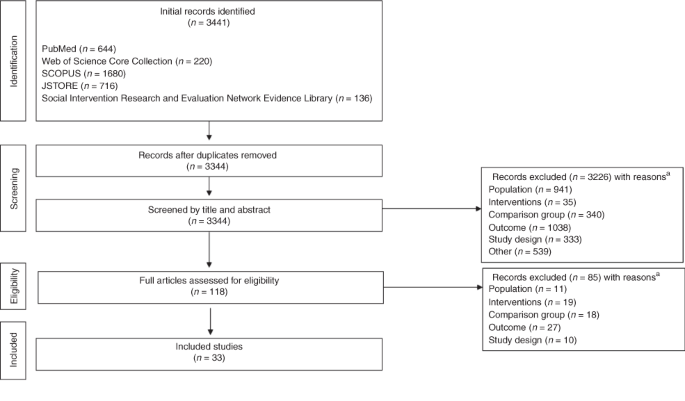

Five data sources (PubMed, Web of Science Core Collection, SCOPUS, JSTORE, and the Social Intervention Research and Evaluation Network Evidence Library) were searched for studies examining the following SDH: poverty, parental educational attainment, housing instability, food insecurity, uninsurance, access to healthcare, and transportation. Studies were selected and coded using the PICOS statement.

The search identified 3441 studies; 33 were included in the final database. All SDH categories were significantly associated with child maltreatment, except that there were no studies on transportation or healthcare. The greatest number of studies were found for poverty ( n = 29), followed by housing instability (13), parental educational attainment (8), food insecurity (1), and uninsurance (1).

Conclusions

SDH, including poverty, parental educational attainment, housing instability, food insecurity, and uninsurance, are associated with child maltreatment. These findings suggest an urgent priority should be routinely screening families for SDH, with referrals to appropriate services, a process that could have the potential to prevent both child maltreatment and subsequent recidivism.

SDH, including poverty, parental educational attainment, housing instability, food insecurity, and uninsurance, are associated with child maltreatment.

No prior published systematic review, to our knowledge, has examined the spectrum of SDH with respect to their associations with child maltreatment.

These findings suggest an urgent priority should be routinely screening families for SDH, with referrals to appropriate services, a process that could have the potential to prevent both child maltreatment and subsequent recidivism

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions

Mechanisms linking social media use to adolescent mental health vulnerability

Investigating child sexual abuse material availability, searches, and users on the anonymous Tor network for a public health intervention strategy

Child maltreatment is a pervasive public health problem in the United States (US). 1 Comprised of acts of commission and omission by a parent or other caregiver (e.g., physical abuse, sexual abuse, and various forms of neglect), 2 child maltreatment is a substantial cause of pediatric injury and death. In 2018, nearly 700,000 childhood victims of nonfatal maltreatment were identified, and an estimated 1770 children died. 1 The combined human and institutional cost attributed to maltreatment morbidity and mortality in the US is estimated to be $124 billion annually. 3

The World Health Organization defines social determinants of health (SDH) as “the conditions in which people are born, grown, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of life.” 4 These conditions are shaped by the distribution of resources, and connect facets of the physical, social, and built environment associated with health outcomes. 5 Among the most commonly recognized SDH (economic stability, education, neighborhood and built environment, health and healthcare, and social and community context), 6 poverty is a major and often overarching factor. Poverty also has been identified as a known risk factor for child maltreatment. 7 Thus, identifying how poverty and other SDH are associated with child maltreatment is a necessary step to develop effective interventions for maltreatment prevention and treatment, and mitigating the risk of associated physical and psychological injury.

Not enough is known about the association of SDH with child maltreatment. Four published systematic reviews have included analyses that examined the relationship between a single or two SDH and maltreatment. Two included socioeconomic status, 8 , 9 one included socioeconomic status and parental educational attainment, 10 and the fourth included immigration status. 11 No published systematic reviews (to our knowledge), however, have examined the spectrum of SDH with respect to their associations with child maltreatment. Therefore, the aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the associations of SDH (including poverty, housing insecurity, food insecurity, uninsurance, healthcare access, and transportation) with child maltreatment.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were selected using the PICOS approach for inclusion and exclusion. 12 , 13 The a priori inclusion criteria for studies were as follows: (1) English-language studies, (2) children 0–18 years old living in the US, (3) peer-reviewed, (4) observational and experimental designs, (5) outcome measures reported for at least one form of maltreatment, and 6) exposure measures for at least one SDH. The exclusion criteria were: (1) specific SDH could not be identified, and (2) conference presentations (e.g., abstracts, posters, or oral presentations).

The outcome of interest was child maltreatment, defined by the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Reauthorization Act of 2010 as “at a minimum, any recent act or failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker, which results in death, serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse or exploitation, or an act or failure to act which presents an imminent risk of serious harm.” 2 Included studies were assessed for the associations of selected SDH—including poverty, food insecurity, housing instability, parental educational attainment, child uninsurance, transportation barriers, and access barriers to healthcare—with child maltreatment. These SDH were chosen because they are domains hypothesized to be most likely associated with child maltreatment and were addressed in a recently published SDH screening instrument used for testing interventions effective in reducing SDH and improving child and caregiver health. 14 Immigration status was not included because of the recent publication of a systematic review examining the association of this SDH with child maltreatment. 11

Data sources

Five data sources were searched through March 2020: (1) PubMed, (2) Web of Science Core Collection, (3) SCOPUS, (4) JSTORE, and (5) the Social Intervention Research and Evaluation Network Evidence Library. All searches contained the following terms: (“Child Abuse”[Mesh] OR “child abuse”[tw] OR “child maltreatment”[tw] OR “child mistreatment”[tw] OR “child neglect”[tw]) AND (“Social Determinants of Health”[Mesh] OR “social determinants of health”[tw] OR “social class”). Searches for terms related to specific SDH varied. A sample search strategy (SCOPUS) can be found in Supplementary Table S 1 (online) .

An effort-to-yield measure of search precision, number needed to read (NNR) was calculated by taking the inverse of the precision of the searches. Precision was calculated by dividing the number of included studies by the number of screened studies, after removal of duplicates. NNR quantifies the number of articles that would be needed to be read before finding one that meets the established inclusion criteria. Dependent on the subject and inclusion criteria, this number provides insights into the time and resources needed for replication, or to conduct a similar study.

Selection of studies

All studies were stored on a Microsoft Excel document detailing the reasons for inclusion or exclusion.

Data abstraction

A codebook was developed using Microsoft Excel. Variables included study characteristics (year of publication, study design and population size, duration, data sources, and level[s] of analysis), sociodemographic characteristics of the study population (child age, racial composition, and sex), SDH under investigation, child maltreatment type (sexual, physical, psychological, neglect, multiple forms, and other), and measures of study quality.

Study quality

A modified version of the Downs and Black checklist was used to assess study quality (Supplementary Table S 2 ). 15 Each item was scored as no (0) or yes (1). The sum of all items ranged from 1 to 8, with higher scores representing a lower risk of bias.

Data synthesis

The criteria for SDH and definitions of child maltreatment varied by study. Therefore, we were unable to combine endpoints in a meta-analysis. Data synthesis at the level of the individual, family, and community were used to analyze included studies.

Study registration

The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020166969).

Study characteristics

Our initial search yielded 3441 studies. After screening by titles and abstracts, 118 met the initial inclusion criteria. Following a full review of 118 studies, 33 were included in the final analysis. The process for selecting included studies is presented in Fig. 1 . Search precision was 0.0096 and the NNR was 104. The characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 1 . Included studies were published from 1978 to 2020. 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 Nine studies used national data, 16 , 23 , 27 , 30 , 36 , 38 , 42 , 43 , 47 and the remaining studies used data from individual states, including 14 from the Midwest, 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 25 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 33 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 45 four from the South, 21 , 22 , 32 , 37 four from the Northeast, 34 , 35 , 46 , 48 one from the West (California), 24 and one from the Pacific (Alaska). 44 Of these studies, 5 conducted chart reviews, 7 used cohort study designs, 7 used a cross-sectional design, and 14 conducted ecological analyses. Included studies assessed the relationship between SDH and child maltreatment at the levels of the individual, zip code, county, and census tracts.

a Studies may have been excluded for multiple reasons.

Study outcomes

Twenty-nine studies explored the association of poverty with child maltreatment. 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 47 Poverty was found to be consistently and strongly associated with maltreatment, with all but three studies identifying a significant association between either familial or community-level poverty and child maltreatment. 16 , 18 , 21 Across studies, poverty was defined by county, 45 neighborhood, 41 familial/household income, 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 23 , 28 , 41 , 42 , 43 socioeconomic status, 44 poverty rate, 21 , 27 , 35 , 40 unemployment, 16 , 17 , 21 , 31 , 32 , 34 , 36 , 40 percentage of families living below the federal poverty level, 24 , 28 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 children living in poverty, 17 , 47 receipt of public assistance, 19 , 25 , 31 , 40 composite impoverishment scores, 26 and self-reported acute financial challenges. 22

In some studies, the relationship between poverty and maltreatment differed by abuse type. For example, one study found that neighborhood poverty was associated with all three forms of child maltreatment, but to different degrees. 38 Another study indicated that financial problems were strongly associated with neglect and abandonment, but the association was less pronounced for sexual abuse. 21

Associations between poverty and maltreatment varied by race/ethnicity. A study comparing predominantly white and black neighborhoods found that the association between poverty and child maltreatment was strongest in whites. 25 Research linking multiple sources of data showed that black children living in poverty were twice as likely to be reported for needs-based neglect than their white counterparts. 26 A recent study showed that when income was held constant, white race was strongly associated with both sexual abuse and neglect, and black race was associated with physical abuse. 27

Housing instability

Thirteen studies examined the relationship between housing instability and child maltreatment. 16 , 18 , 20 , 21 , 23 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 40 , 46 Most studies revealed that housing instability is associated with child maltreatment. Among these studies, the definition of housing stability varied, and included percent vacancy, 21 , 26 , 32 , 33 , 40 rates of foreclosure and delinquency, 16 , 18 , 34 hazardous living conditions, 29 and instability/mobility (>1 move per year). 20 , 23 , 28 Only one study examined homelessness, performing an analysis of hospital and pediatric ambulatory records of children <18 years old. 46 After matching families on income, homeless children were found to have higher rates of maltreatment-related emergency-department (ED) visits and child maltreatment than their nonhomeless counterparts. One study found that displacement due to foreclosure, eviction, or mortgage delinquency was associated with maltreatment investigations. 34 Two studies documented that housing instability/mobility (>1 move per year) was associated with child protective service (CPS) reports and maltreatment risk. 20 , 23

Two studies found no association between housing insecurity and child maltreatment. 18 , 28 In the first, housing instability consisted of an aggregate measure of material hardship, including difficulty paying rent, eviction, or having experienced any utility shutoff in the previous year. 18 In the second, housing instability was measured by residential mobility. 28

Several studies reported differences in the association between housing stability and child maltreatment type. Two identified an association between the percent of vacant housing in communities and sexual abuse. 21 , 32 Another study found that hazardous housing conditions were associated with neglect, but not physical abuse; a history of housing instability increased the strength of this association. 29 One study found that mortgage delinquency was associated with traumatic brain injury and other forms of physical abuse. 20

Food insecurity

Just one study examined the relationship between food insecurity and child maltreatment. 30 An analysis of a national sample from the Fragile Families and Childhood Wellbeing Study revealed that, compared with food-secure households, food-insecure households experienced increased rates of total parental aggression (7% vs. 20%, respectively). Controlling for maternal characteristics did not attenuate this association.

Parental educational attainment

Eight studies considered the relationship between parental educational attainment and child maltreatment. 17 , 18 , 20 , 24 , 25 , 32 , 41 , 42 The results of most studies indicate that low parental educational attainment is associated with child maltreatment. Parental educational attainment was defined as high-school completion in six studies, 17 , 18 , 20 , 32 , 41 , 42 maternal education level in one, 25 and completion of postsecondary education in the last. 24 Two studies found no association. 18 , 24 Notably, one of these studied failed to report victim and perpetrator demographic characteristics (age, sex, or race/ethnicity), 18 and the other relied on self-reported data. 24

Uninsurance

One study was identified that examined the association of the child lacking health insurance with child maltreatment. 48 This study reported that a higher proportion of preadolescent children seen in the ED with suspected sexual child abuse were uninsured, compared with a control group of children seen in the ED with upper-limb fractures, at 52% vs. 1%, respectively. No statistical analyses, however, were conducted, nor is it clear whether there was matching of cases and controls by age, sex, or other relevant characteristics.

The search did not reveal any studies that examined the associations of transportation or access to healthcare with child maltreatment.

Multiple studies document that SDH, including poverty, housing instability, food insecurity, low parental educational attainment, and child uninsurance, are significantly associated with child maltreatment. A recent systematic review also concluded that although the immigrant parental status is associated with a lower likelihood of overall child maltreatment, it may be associated with a higher risk of child neglect and neglectful supervision. 11 Taken together, these findings suggest that an urgent priority, therefore, should be to routinely screen families for SDH in inpatient and outpatient settings and in CPS, and to address identified SDH with referrals to appropriate services. This screening and referral process could have the potential to not only prevent child maltreatment by reducing or eliminating the SDH before they result in maltreatment, but might also decrease the risk of maltreatment recidivism in families in which maltreatment already has occurred. The American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, and the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine all have endorsed SDH screening and service referral. 49 , 50 , 51 Several studies document that patients and caregivers are comfortable with completing SDH screening. 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 Addressing SDH by referral to such services as case managers, social workers, housing vouchers, medical–legal partnerships, and parent mentors, already has been shown to reduce hospitalizations, improve housing quality and stability, enhance economic security, improve healthcare outcomes, insure more uninsured children, increase the quality of care, empower parents, and save money for society, 57 thereby holding great promise as interventions that may prove effective in ultimately reducing or preventing child maltreatment.

Poverty was the SDH for which the greatest number of studies documented an association with child maltreatment. Although few studies have investigated the temporal relationship between poverty and child maltreatment, 8 there is evidence that families living in poverty are more likely to be reported to CPS for neglect. 58 Poverty sequelae, such as inability to feed, clothe, or house a child, overlap with the definition of child neglect, so it is important to distinguish intentional neglect from family challenges related to living in poverty. Differential or alternative response is one CPS approach that addresses maltreatment reports by attending to unmet family needs. 59 An analysis of the effectiveness of this form of intervention has shown that families living in poverty benefit most from this approach. 60 To date, this response has been implemented at the individual and family levels. Extending differential or alternative response to the community level may be an effective strategy for families living in impoverished neighborhoods, where racial biases in child maltreatment reports and investigations have been identified.

The study results underscore several unanswered questions regarding the association between SDH and child maltreatment. First, it is unclear whether transportation barriers or impaired access to healthcare are associated with child maltreatment, given that no studies were identified on these SDH. Second, because the definitions for each SDH varied considerably within and across studies (especially for poverty), it is unclear whether more consistent SDH definitions would yield different findings. Third, because males as caregivers and heads of household were under-represented and often excluded from some study populations, 20 , 23 , 25 , 33 an unanswered question is whether there are associations of paternal educational attainment and other male-caregiver SDHs with child maltreatment. Although single mothers have been identified as an at-risk population for maltreatment perpetration, it is equally important to examine the role that men play in maltreatment. In a previous analysis, the first author identified men as the predominant perpetrator in 58% of cases of fatal maltreatment in the US. 61 Results of our study emphasize the need for research inclusive of male caregivers, to identify and mitigate risk factors before they escalate to maltreatment fatalities. Fourth, most studies focusing on sexual abuse were primarily limited to female populations, 32 despite evidence that male children also are victims of sexual abuse. There is an urgent need to investigate how SDH perpetuate or protect against sexual abuse in male children, so that prevention efforts can be tailored by sex. Finally, because most studies combined maltreatment into one aggregate category, an unanswered question is what are the associations of SDH with specific maltreatment categories. It has been posited that each maltreatment type has a unique etiology, and lumping these types into one category likely attenuates the ability to identify meaningful associations. Although few studies in this systematic review disaggregated by maltreatment categories, those that did found significant differences in maltreatment risk according to the SDH examined.

Based on the study findings, a research agenda is proposed to address key issues regarding the association of SDH with child maltreatment. Research is needed to address the aforementioned identified research gaps, including studies on transportation barriers, impaired access to healthcare, consistently defined SDH, SDH for male caregivers, and the associations of SDH with specific maltreatment categories and male victims of sexual abuse. Studies are needed to determine whether there is a direct association between the number of SDH and the risk of maltreatment, and whether the presence of multiple SDH can synergistically increase maltreatment risk. Research is urgently needed to determine whether SDH screening and referral to appropriate services result in SDH reduction and elimination as well as decreases in or the prevention of child maltreatment and maltreatment recidivism.

Limitations and strengths

Certain study limitations should be noted. First, as with all systematic reviews, the quality of this analysis is limited by the scientific rigor of included studies. Second, studies were selected based on the search criteria. It is possible that relevant literature was missed because of the heterogeneity of terms used to describe the various SDH and child maltreatment. Third, many included studies were cross-sectional or ecological, preventing the ability to draw conclusions about the temporal relationship between SDH and child maltreatment. Fourth, many data sources for the included studies used administrative data derived from CPS. In most instances, these records only included reports of maltreatment that were screened in and accepted for either an investigation or alternative response. As a result, these data sources likely exclude many cases of maltreatment, given evidence demonstrating equivalent risk of incidence and recurrence between maltreatment reports and substantiations. 28 , 38

SDH, including poverty, parental educational attainment, housing instability, food insecurity, and uninsurance, are associated with child maltreatment. These findings suggest that an urgent priority should be routinely screening families for SDH, with referrals to appropriate services, a process that could have the potential to prevent both child maltreatment and subsequent recidivism. Unanswered questions include whether SDH are associated with specific maltreatment categories and male victims of sexual abuse, and whether transportation barriers, impaired access to healthcare, consistently defined SDH, and SDH for male caregivers are associated with child maltreatment. A proposed research agenda includes addressing these unanswered questions; determining whether there is a direct association between the number of SDH and the risk of maltreatment, and whether the presence of multiple SDH can synergistically increase maltreatment risk; and investigations on whether SDH screening and referral to appropriate services result in SDH reduction and elimination, as well as decreases in or the prevention of child maltreatment and maltreatment recidivism.

US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. Child maltreatment 2018. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/resource/child-maltreatment-2018 (2020).

US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth, and Families, Children’s Bureau. The Child Abuse Prevention And Treatment Act (CAPTA) 2010, Washington, DC. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/capta.pdf (2011).

Fang, X., Brown, D. S., Florence, C. S. & Mercy, J. A. The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States and implications for prevention. Child Abuse Negl. 36 , 156–165 (2012).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

World Health Organization. About social determinants of health. https://www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en/ (2020).

US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Establishing a Holistic Framework to Reduce Inequities in HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STDs, and Tuberculosis in the United States . (US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, 2010).

Healthy People 2020. Social determinants of health. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health (2020).

Fortson, B. L., Klevens, J., Merrick, M. T., Gilbert, L. K. & Alexander, S. P. Preventing Child Abuse and Neglect: A Technical Package for Policy, Norm, and Programmatic Activities (National Center for Injury Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016).

Conrad-Hiebner, A. & Byram, E. The temporal impact of economic insecurity on child maltreatment: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse 21 , 157–178 (2020).

PubMed Google Scholar

Stith, S. M. et al. Risk factors in child maltreatment: a meta analytic review of the literature. Aggress. Violent Behav. 14 , 13–29 (2009).

Google Scholar

Connell-Carrick, K. A critical review of the empirical literature: identifying correlates of child neglect. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 20 , 389–425 (2003).

Millett, L. S. The healthy immigrant paradox and child maltreatment: a systematic review. J. Immigr. Minor Health 18 , 1199–1215 (2016).

Higgins, J. P. & Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions , Vol. 4 (Wiley, Hoboken, 2011).

Littlel, J. H., Corcoran, J. & Pillai, V. K. Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (Oxford University Press, New York, 2008).

Gottlieb, L. M. et al. Effects of in-person assistance vs personalized written resources about social services on household social risks and child and caregiver health: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 3 , e200701 (2020).

Downs, S. H. & Black, N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 52 , 377–384 (1998).

CAS Google Scholar

Wood, J. N. et al. Local macroeconomic trends and hospital admissions for child abuse, 2000-2009. Pediatrics 130 , e358–364 (2012).

Weissman, A. M., Jogerst, G. J. & Dawson, J. D. Community characteristics associated with child abuse in Iowa. Child Abuse Negl. 27 , 1145–1159 (2003).

Slack, K. S., Holl, J. L., McDaniel, M., Yoo, J. & Bolger, K. Understanding the risks of child neglect: an exploration of poverty and parenting characteristics. Child Maltreatment 9 , 395–408 (2004).

Slack, K. et al. Child protective intervention in the context of welfare reform: the effects of work and welfare on maltreatment reports. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 22 , 517–536 (2003).

Slack, K. S., Font, S., Maguire-Jack, K. & Berger, L. M. Predicting child protective services (CPS) involvement among low-income U.S. families with young children receiving nutritional assistance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14 , 1197 (2017).

PubMed Central Google Scholar

Morris, M. C. et al. Connecting child maltreatment risk with crime and neighborhood disadvantage across time and place: a bayesian spatiotemporal analysis. Child Maltreatment 24 , 181–192 (2019).

Martin, M. J. & Walters, J. Familial correlates of selected types of child abuse and neglect. J. Marriage Fam. 44 , 267–276 (1982).

Marcal, K. E. The impact of housing instability on child maltreatment: a causal investigation. J. Fam. Soc. Work 21 , 331–347 (2018).

Maguire-Jack, K. & Font, S. A. Community and individual risk factors for physical child abuse and child neglect: variations by poverty status. Child Maltreatment 22 , 215–226 (2017).

Koch, J. et al. Risk of child abuse or neglect in a cohort of low-income children. Child Abuse Negl . 19 , 291–295 (1995).

Korbin, J. E., Coulton, C. J., Chard, S., Platt-Houston, C. & Su, M. Impoverishment and child maltreatment in African American and European American neighborhoods. Dev. Psychopathol. 10 , 215–233 (1998).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kim, H. & Drake, B. Child maltreatment risk as a function of poverty and race/ethnicity in the USA. Int. J. Epidemiol. 47 , 780–787 (2018).

Jonson-Reid, M., Drake, B. & Zhou, P. Neglect subtypes, race, and poverty: individual, family, and service characteristics. Child Maltreatment 18 , 30–41 (2013).

Hirsch, B. K., Yang, M. Y., Font, S. & Slack, K. S. Physically hazardous housing and risk for child protective services involvement. Child Welf. 94 , 87–104 (2015).

Helton, J. J., Jackson, D. B., Boutwell, B. B. & Vaughn, M. G. Household food insecurity and parent-to-child aggression. Child Maltreatment 24 , 213–221 (2019).

Gross-Manos, D. et al. Why does child maltreatment occur? Caregiver perspectives and analyses of neighborhood structural factors across twenty years. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 99 , 138–145 (2019).

Greeley, S. C. et al. Community characteristics associated with seeking medical evaluation for suspected child sexual abuse in greater Houston. J. Prim. Prev. 37 , 215–230 (2016).

Garbarino, J. & Crouter, A. Defining the community context for parent-child relations: the correlates of child maltreatment. Child Dev. 49 , 604–616 (1978).

Frioux, S. et al. Longitudinal association of county-level economic indicators and child maltreatment incidents. Matern. Child Health J. 18 , 2202–2208 (2014).

Fong, K. Neighborhood inequality in the prevalence of reported and substantiated child maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl. 90 , 13–21 (2019).

Farrell, C. A. et al. Community poverty and child abuse fatalities in the United States. Pediatrics 139 , e20161616 (2017).

Ernst, J. S. Community-level factors and child maltreatment in a suburban county. Soc. Work Res. 25 , 133–142 (2001).

Eckenrode, J., Smith, E. G., McCarthy, M. E. & Dineen, M. Income inequality and child maltreatment in the United States. Pediatrics 133 , 454–461 (2014).

Drake, B. & Pandey, S. Understanding the relationship between neighborhood poverty and specific types of child maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl. 20 , 1003–1018 (1996).

Coulton, C. J., Richter, F. G., Korbin, J., Crampton, D. & Spilsbury, J. C. Understanding trends in neighborhood child maltreatment rates: a three-wave panel study 1990-2010. Child Abuse Negl. 84 , 170–181 (2018).

Coulton, C. J., Korbin, J. E. & Su, M. Neighborhoods and child maltreatment: a multi-level study. Child Abuse Negl. 23 , 1019–1040 (1999).

Berger, L. Socioeconomic factors and substandard parenting. Soc. Serv. Rev. 81 , 485–522 (2007).

Berger, L. M., Font, S. A., Slack, K. S. & Waldfogel, J. Income and child maltreatment in unmarried families: evidence from the earned income tax credit. Rev. Econ. House. 15 , 1345–1372 (2017).

Austin, A. E. et al. Heterogeneity in risk and protection among Alaska Native/American Indian and Non-Native children. Prev. Sci. 21 , 86–97 (2020).

Anderson, B. L., Pomerantz, W. J. & Gittelman, M. A. Intentional injuries in young Ohio children: is there urban/rural variation? J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 77 , S36–40 (2014).

Alperstein, G., Rappaport, C. & Flanigan, J. M. Health problems of homeless children in New York City. Am. J. Public Health 78 , 1232–1233 (1988).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Moore, K. A., Nord, C. W. & Peterson, J. L. Nonvoluntary sexual activity among adolescents. Fam. Plann. Perspect. 21 , 110–114 (1989).

Kupfer, G. M. & Giardino, A. P. Reimbursement and insurance coverage in cases of suspected sexual abuse in the emergency department. Child Abuse Negl. 19 , 291–295 (1995).

Council on Community Pediatrics. Poverty and child health in the United States. Pediatrics . 137 , 1–14 (2016).

American Academy of Physicians. The EveryONE project: screening tools and resources to advance health equity. https://www.aafp.org/patient-care/social-determinants-of-health/everyone-project/eop-tools.html (2020).

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Integrating Social Care into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation’s Health (National Academies Press, Washington, 2019).

De Marchis, E. H., Alderwick, H. & Gottlieb, L. M. Do patients want help addressing social risks? J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 33 , 170–175 (2020).

De Marchis, E. H. et al. Part I: a quantitative study of social risk screening acceptability in patients and caregivers. Am. J. Prev. Med. 57 , S25–S37 (2019).

Wylie, S. A. et al. Assessing and referring adolescents’ health-related social problems: qualitative evaluation of a novel web-based approach. J. Telemed. Telecare 18 , 392–398 (2012).

Hassan, A. et al. Youths’ health-related social problems: concerns often overlooked during the medical visit. J. Adolesc. Health 53 , 265–271 (2013).

Byhoff, E. et al. Part II. A qualitative study of social risk screening acceptability in patients and caregivers. Am. J. Prev. Med. 57 , S38–S46 (2019).

Hogan, A. H. & Flores, G. Social determinants of health and the hospitalized child. Hosp. Pediatr. 10 , 101–103 (2020).

Yang, M. Y. The effect of material hardship on child protective service involvement. Child Abuse Negl. 41 , 113–125 (2015).

Child Welfare Information Gateway. Differential Response to Reports of Child Abuse and Neglect (US Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau, Washington, 2014).

Siegel, G. L. Lessons from the Beginning of Differential Response: Why it Works and When it Doesn’t (Institute of Applied Research, St. Louis, 2012); retrieved from http://www.iarstl.org/papers/DRLessons.pdf (2012).

Hunter, A. A., DiVietro, S., Scwab-Reese, L. & Riffon, M. An epidemiologic examination of perpetrators of fatal child maltreatment using the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS). J. Interpers. Violence 886260519851787 (2019).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Marissa Gauthier for her assistance with the initial citation search.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Injury Prevention Center, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center and Hartford Hospital, Hartford, CT, USA

Amy A. Hunter