- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 7, 2019 | Original: November 9, 2009

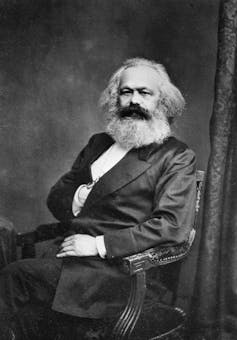

As a university student, Karl Marx (1818-1883) joined a movement known as the Young Hegelians, who strongly criticized the political and cultural establishments of the day. He became a journalist, and the radical nature of his writings would eventually get him expelled by the governments of Germany, France and Belgium. In 1848, Marx and fellow German thinker Friedrich Engels published “The Communist Manifesto,” which introduced their concept of socialism as a natural result of the conflicts inherent in the capitalist system. Marx later moved to London, where he would live for the rest of his life. In 1867, he published the first volume of “Capital” (Das Kapital), in which he laid out his vision of capitalism and its inevitable tendencies toward self-destruction, and took part in a growing international workers’ movement based on his revolutionary theories.

Karl Marx’s Early Life and Education

Karl Marx was born in 1818 in Trier, Prussia; he was the oldest surviving boy in a family of nine children. Both of his parents were Jewish, and descended from a long line of rabbis, but his father, a lawyer, converted to Lutheranism in 1816 due to contemporary laws barring Jews from higher society. Young Karl was baptized in the same church at the age of 6, but later became an atheist.

Did you know? The 1917 Russian Revolution, which overthrew three centuries of tsarist rule, had its roots in Marxist beliefs. The revolution’s leader, Vladimir Lenin, built his new proletarian government based on his interpretation of Marxist thought, turning Karl Marx into an internationally famous figure more than 30 years after his death.

After a year at the University of Bonn (during which Marx was imprisoned for drunkenness and fought a duel with another student), his worried parents enrolled their son at the University of Berlin, where he studied law and philosophy. There he was introduced to the philosophy of the late Berlin professor G.W.F. Hegel and joined a group known as the Young Hegelians, who were challenging existing institutions and ideas on all fronts, including religion, philosophy, ethics and politics.

Karl Marx Becomes a Revolutionary

After receiving his degree, Marx began writing for the liberal democratic newspaper Rheinische Zeitung, and he became the paper’s editor in 1842. The Prussian government banned the paper as too radical the following year. With his new wife, Jenny von Westphalen, Marx moved to Paris in 1843. There Marx met fellow German émigré Friedrich Engels, who would become his lifelong collaborator and friend. In 1845, Engels and Marx published a criticism of Bauer’s Young Hegelian philosophy entitled “The Holy Father.”

By that time, the Prussian government intervened to get Marx expelled from France, and he and Engels had moved to Brussels, Belgium, where Marx renounced his Prussian citizenship. In 1847, the newly founded Communist League in London, England, drafted Marx and Engels to write “The Communist Manifesto,” published the following year. In it, the two philosophers depicted all of history as a series of class struggles (historical materialism), and predicted that the upcoming proletarian revolution would sweep aside the capitalist system for good, making the workingmen the new ruling class of the world.

Karl Marx’s Life in London and “Das Kapital”

With revolutionary uprisings engulfing Europe in 1848, Marx left Belgium just before being expelled by that country’s government. He briefly returned to Paris and Germany before settling in London, where he would live for the rest of his life, despite being denied British citizenship. He worked as a journalist there, including 10 years as a correspondent for the New York Daily Tribune, but never quite managed to earn a living wage, and was supported financially by Engels. In time, Marx became increasingly isolated from fellow London Communists, and focused more on developing his economic theories. In 1864, however, he helped found the International Workingmen’s Association (known as the First International) and wrote its inaugural address. Three years later, Marx published the first volume of “Capital” (Das Kapital) his masterwork of economic theory. In it he expressed a desire to reveal “the economic law of motion of modern society” and laid out his theory of capitalism as a dynamic system that contained the seeds of its own self-destruction and subsequent triumph of communism. Marx would spend the rest of his life working on manuscripts for additional volumes, but they remained unfinished at the time of his death, of pleurisy, on March 14, 1883.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Table of Contents

- New in this Archive

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Karl Marx (1818–1883) is best known not as a philosopher but as a revolutionary, whose works inspired the foundation of many communist regimes in the twentieth century. It is hard to think of many who have had as much influence in the creation of the modern world. Trained as a philosopher, Marx turned away from philosophy in his mid-twenties, towards economics and politics. However, in addition to his overtly philosophical early work, his later writings have many points of contact with contemporary philosophical debates, especially in the philosophy of history and the social sciences, and in moral and political philosophy. Historical materialism — Marx’s theory of history — is centered around the idea that forms of society rise and fall as they further and then impede the development of human productive power. Marx sees the historical process as proceeding through a necessary series of modes of production, characterized by class struggle, culminating in communism. Marx’s economic analysis of capitalism is based on his version of the labour theory of value, and includes the analysis of capitalist profit as the extraction of surplus value from the exploited proletariat. The analysis of history and economics come together in Marx’s prediction of the inevitable economic breakdown of capitalism, to be replaced by communism. However Marx refused to speculate in detail about the nature of communism, arguing that it would arise through historical processes, and was not the realisation of a pre-determined moral ideal.

1. Marx’s Life and Works

- 2.1. On The Jewish Question

- 2.2. Contribution to a Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right: Introduction

- 2.3. 1844 Manuscripts

- 2.4. Theses on Feuerbach

3. Economics

4.1 the german ideology, 4.2 1859 preface, 4.3 functional explanation, 4.4 rationality, 4.5 alternative interpretations, 5. morality, other internet resources, related entries.

Karl Marx was born in Trier, in the German Rhineland, in 1818. Although his family was Jewish they converted to Christianity so that his father could pursue his career as a lawyer in the face of Prussia’s anti-Jewish laws. A precocious schoolchild, Marx studied law in Bonn and Berlin, and then wrote a PhD thesis in Philosophy, comparing the views of Democritus and Epicurus. On completion of his doctorate in 1841 Marx hoped for an academic job, but he had already fallen in with too radical a group of thinkers and there was no real prospect. Turning to journalism, Marx rapidly became involved in political and social issues, and soon found himself having to consider communist theory. Of his many early writings, four, in particular, stand out. ‘Contribution to a Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Introduction’, and ‘On The Jewish Question’, were both written in 1843 and published in the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher. The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts , written in Paris 1844, and the ‘Theses on Feuerbach’ of 1845, remained unpublished in Marx’s lifetime.

The German Ideology , co-written with Engels in 1845, was also unpublished but this is where we see Marx beginning to develop his theory of history. The Communist Manifesto is perhaps Marx’s most widely read work, even if it is not the best guide to his thought. This was again jointly written with Engels and published with a great sense of excitement as Marx returned to Germany from exile to take part in the revolution of 1848. With the failure of the revolution Marx moved to London where he remained for the rest of his life. He now concentrated on the study of economics, producing, in 1859, his Contribution to a Critique of Political Economy . This is largely remembered for its Preface, in which Marx sketches out what he calls ‘the guiding principles’ of his thought, on which many interpretations of historical materialism are based. Marx’s main economic work is, of course, Capital (Volume 1), published in 1867, although Volume 3, edited by Engels, and published posthumously in 1894, contains much of interest. Finally, the late pamphlet Critique of the Gotha Programme (1875) is an important source for Marx’s reflections on the nature and organisation of communist society.

The works so far mentioned amount only to a small fragment of Marx’s opus, which will eventually run to around 100 large volumes when his collected works are completed. However the items selected above form the most important core from the point of view of Marx’s connection with philosophy, although other works, such as the 18 th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon (1852), are often regarded as equally important in assessing Marx’s analysis of concrete political events. In what follows, I shall concentrate on those texts and issues that have been given the greatest attention within the Anglo-American philosophical literature.

2. The Early Writings

The intellectual climate within which the young Marx worked was dominated by the influence of Hegel, and the reaction to Hegel by a group known as the Young Hegelians, who rejected what they regarded as the conservative implications of Hegel’s work. The most significant of these thinkers was Ludwig Feuerbach, who attempted to transform Hegel’s metaphysics, and, thereby, provided a critique of Hegel’s doctrine of religion and the state. A large portion of the philosophical content of Marx’s works written in the early 1840s is a record of his struggle to define his own position in reaction to that of Hegel and Feuerbach and those of the other Young Hegelians.

2.1 ‘On The Jewish Question’

In this text Marx begins to make clear the distance between himself and his radical liberal colleagues among the Young Hegelians; in particular Bruno Bauer. Bauer had recently written against Jewish emancipation, from an atheist perspective, arguing that the religion of both Jews and Christians was a barrier to emancipation. In responding to Bauer, Marx makes one of the most enduring arguments from his early writings, by means of introducing a distinction between political emancipation — essentially the grant of liberal rights and liberties — and human emancipation. Marx’s reply to Bauer is that political emancipation is perfectly compatible with the continued existence of religion, as the contemporary example of the United States demonstrates. However, pushing matters deeper, in an argument reinvented by innumerable critics of liberalism, Marx argues that not only is political emancipation insufficient to bring about human emancipation, it is in some sense also a barrier. Liberal rights and ideas of justice are premised on the idea that each of us needs protection from other human beings who are a threat to our liberty and security. Therefore liberal rights are rights of separation, designed to protect us from such perceived threats. Freedom on such a view, is freedom from interference. What this view overlooks is the possibility — for Marx, the fact — that real freedom is to be found positively in our relations with other people. It is to be found in human community, not in isolation. Accordingly, insisting on a regime of rights encourages us to view each other in ways that undermine the possibility of the real freedom we may find in human emancipation. Now we should be clear that Marx does not oppose political emancipation, for he sees that liberalism is a great improvement on the systems of feud and religious prejudice and discrimination which existed in the Germany of his day. Nevertheless, such politically emancipated liberalism must be transcended on the route to genuine human emancipation. Unfortunately, Marx never tells us what human emancipation is, although it is clear that it is closely related to the idea of non-alienated labour, which we will explore below.

2.2 ‘Contribution to a Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Introduction’

This work is home to Marx’s notorious remark that religion is the ‘opiate of the people’, a harmful, illusion-generating painkiller, and it is here that Marx sets out his account of religion in most detail. Just as importantly Marx here also considers the question of how revolution might be achieved in Germany, and sets out the role of the proletariat in bringing about the emancipation of society as a whole.

With regard to religion, Marx fully accepted Feuerbach’s claim in opposition to traditional theology that human beings had invented God in their own image; indeed a view that long pre-dated Feuerbach. Feuerbach’s distinctive contribution was to argue that worshipping God diverted human beings from enjoying their own human powers. While accepting much of Feuerbach’s account Marx’s criticizes Feuerbach on the grounds that he has failed to understand why people fall into religious alienation and so is unable to explain how it can be transcended. Feuerbach’s view appears to be that belief in religion is purely an intellectual error and can be corrected by persuasion. Marx’s explanation is that religion is a response to alienation in material life, and therefore cannot be removed until human material life is emancipated, at which point religion will wither away. Precisely what it is about material life that creates religion is not set out with complete clarity. However, it seems that at least two aspects of alienation are responsible. One is alienated labour, which will be explored shortly. A second is the need for human beings to assert their communal essence. Whether or not we explicitly recognize it, human beings exist as a community, and what makes human life possible is our mutual dependence on the vast network of social and economic relations which engulf us all, even though this is rarely acknowledged in our day-to-day life. Marx’s view appears to be that we must, somehow or other, acknowledge our communal existence in our institutions. At first it is ‘deviously acknowledged’ by religion, which creates a false idea of a community in which we are all equal in the eyes of God. After the post-Reformation fragmentation of religion, where religion is no longer able to play the role even of a fake community of equals, the state fills this need by offering us the illusion of a community of citizens, all equal in the eyes of the law. Interestingly, the political liberal state, which is needed to manage the politics of religious diversity, takes on the role offered by religion in earlier times of providing a form of illusory community. But the state and religion will both be transcended when a genuine community of social and economic equals is created.

Of course we are owed an answer to the question how such a society could be created. It is interesting to read Marx here in the light of his third Thesis on Feuerbach where he criticises an alternative theory. The crude materialism of Robert Owen and others assumes that human beings are fully determined by their material circumstances, and therefore to bring about an emancipated society it is necessary and sufficient to make the right changes to those material circumstances. However, how are those circumstances to be changed? By an enlightened philanthropist like Owen who can miraculously break through the chain of determination which ties down everyone else? Marx’s response, in both the Theses and the Critique, is that the proletariat can break free only by their own self-transforming action. Indeed if they do not create the revolution for themselves — in alliance, of course, with the philosopher — they will not be fit to receive it.

2.3 Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts

The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts cover a wide range of topics, including much interesting material on private property and communism, and on money, as well as developing Marx’s critique of Hegel. However, the manuscripts are best known for their account of alienated labour. Here Marx famously depicts the worker under capitalism as suffering from four types of alienated labour. First, from the product, which as soon as it is created is taken away from its producer. Second, in productive activity (work) which is experienced as a torment. Third, from species-being, for humans produce blindly and not in accordance with their truly human powers. Finally, from other human beings, where the relation of exchange replaces the satisfaction of mutual need. That these categories overlap in some respects is not a surprise given Marx’s remarkable methodological ambition in these writings. Essentially he attempts to apply a Hegelian deduction of categories to economics, trying to demonstrate that all the categories of bourgeois economics — wages, rent, exchange, profit, etc. — are ultimately derived from an analysis of the concept of alienation. Consequently each category of alienated labour is supposed to be deducible from the previous one. However, Marx gets no further than deducing categories of alienated labour from each other. Quite possibly in the course of writing he came to understand that a different methodology is required for approaching economic issues. Nevertheless we are left with a very rich text on the nature of alienated labour. The idea of non-alienation has to be inferred from the negative, with the assistance of one short passage at the end of the text ‘On James Mill’ in which non-alienated labour is briefly described in terms which emphasise both the immediate producer’s enjoyment of production as a confirmation of his or her powers, and also the idea that production is to meet the needs of others, thus confirming for both parties our human essence as mutual dependence. Both sides of our species essence are revealed here: our individual human powers and our membership in the human community.

It is important to understand that for Marx alienation is not merely a matter of subjective feeling, or confusion. The bridge between Marx’s early analysis of alienation and his later social theory is the idea that the alienated individual is ‘a plaything of alien forces’, albeit alien forces which are themselves a product of human action. In our daily lives we take decisions that have unintended consequences, which then combine to create large-scale social forces which may have an utterly unpredicted, and highly damaging, effect. In Marx’s view the institutions of capitalism — themselves the consequences of human behaviour — come back to structure our future behaviour, determining the possibilities of our action. For example, for as long as a capitalist intends to stay in business he must exploit his workers to the legal limit. Whether or not wracked by guilt the capitalist must act as a ruthless exploiter. Similarly the worker must take the best job on offer; there is simply no other sane option. But by doing this we reinforce the very structures that oppress us. The urge to transcend this condition, and to take collective control of our destiny — whatever that would mean in practice — is one of the motivating and sustaining elements of Marx’s social analysis.

2.4 ‘Theses on Feuerbach’

The Theses on Feuerbach contain one of Marx’s most memorable remarks: “the philosophers have only interpreted the world, the point is to change it” (thesis 11). However the eleven theses as a whole provide, in the compass of a couple of pages, a remarkable digest of Marx’s reaction to the philosophy of his day. Several of these have been touched on already (for example, the discussions of religion in theses 4, 6 and 7, and revolution in thesis 3) so here I will concentrate only on the first, most overtly philosophical, thesis.

In the first thesis Marx states his objections to ‘all hitherto existing’ materialism and idealism. Materialism is complimented for understanding the physical reality of the world, but is criticised for ignoring the active role of the human subject in creating the world we perceive. Idealism, at least as developed by Hegel, understands the active nature of the human subject, but confines it to thought or contemplation: the world is created through the categories we impose upon it. Marx combines the insights of both traditions to propose a view in which human beings do indeed create — or at least transform — the world they find themselves in, but this transformation happens not in thought but through actual material activity; not through the imposition of sublime concepts but through the sweat of their brow, with picks and shovels. This historical version of materialism, which transcends and thus rejects all existing philosophical thought, is the foundation of Marx’s later theory of history. As Marx puts it in the 1844 Manuscripts, ‘Industry is the real historical relationship of nature … to man’. This thought, derived from reflection on the history of philosophy, together with his experience of social and economic realities, as a journalist, sets the agenda for all Marx’s future work.

Capital Volume 1 begins with an analysis of the idea of commodity production. A commodity is defined as a useful external object, produced for exchange on a market. Thus two necessary conditions for commodity production are the existence of a market, in which exchange can take place, and a social division of labour, in which different people produce different products, without which there would be no motivation for exchange. Marx suggests that commodities have both use-value — a use, in other words — and an exchange-value — initially to be understood as their price. Use value can easily be understood, so Marx says, but he insists that exchange value is a puzzling phenomenon, and relative exchange values need to be explained. Why does a quantity of one commodity exchange for a given quantity of another commodity? His explanation is in terms of the labour input required to produce the commodity, or rather, the socially necessary labour, which is labour exerted at the average level of intensity and productivity for that branch of activity within the economy. Thus the labour theory of value asserts that the value of a commodity is determined by the quantity of socially necessary labour time required to produce it. Marx provides a two stage argument for the labour theory of value. The first stage is to argue that if two objects can be compared in the sense of being put on either side of an equals sign, then there must be a ‘third thing of identical magnitude in both of them’ to which they are both reducible. As commodities can be exchanged against each other, there must, Marx argues, be a third thing that they have in common. This then motivates the second stage, which is a search for the appropriate ‘third thing’, which is labour in Marx’s view, as the only plausible common element. Both steps of the argument are, of course, highly contestable.

Capitalism is distinctive, Marx argues, in that it involves not merely the exchange of commodities, but the advancement of capital, in the form of money, with the purpose of generating profit through the purchase of commodities and their transformation into other commodities which can command a higher price, and thus yield a profit. Marx claims that no previous theorist has been able adequately to explain how capitalism as a whole can make a profit. Marx’s own solution relies on the idea of exploitation of the worker. In setting up conditions of production the capitalist purchases the worker’s labour power — his ability to labour — for the day. The cost of this commodity is determined in the same way as the cost of every other; i.e. in terms of the amount of socially necessary labour power required to produce it. In this case the value of a day’s labour power is the value of the commodities necessary to keep the worker alive for a day. Suppose that such commodities take four hours to produce. Thus the first four hours of the working day is spent on producing value equivalent to the value of the wages the worker will be paid. This is known as necessary labour. Any work the worker does above this is known as surplus labour, producing surplus value for the capitalist. Surplus value, according to Marx, is the source of all profit. In Marx’s analysis labour power is the only commodity which can produce more value than it is worth, and for this reason it is known as variable capital. Other commodities simply pass their value on to the finished commodities, but do not create any extra value. They are known as constant capital. Profit, then, is the result of the labour performed by the worker beyond that necessary to create the value of his or her wages. This is the surplus value theory of profit.

It appears to follow from this analysis that as industry becomes more mechanised, using more constant capital and less variable capital, the rate of profit ought to fall. For as a proportion less capital will be advanced on labour, and only labour can create value. In Capital Volume 3 Marx does indeed make the prediction that the rate of profit will fall over time, and this is one of the factors which leads to the downfall of capitalism. (However, as pointed out by Marx’s able expositor Paul Sweezy in The Theory of Capitalist Development , the analysis is problematic.) A further consequence of this analysis is a difficulty for the theory that Marx did recognise, and tried, albeit unsuccessfully, to meet also in Capital Volume 3. It follows from the analysis so far that labour intensive industries ought to have a higher rate of profit than those which use less labour. Not only is this empirically false, it is theoretically unacceptable. Accordingly, Marx argued that in real economic life prices vary in a systematic way from values. Providing the mathematics to explain this is known as the transformation problem, and Marx’s own attempt suffers from technical difficulties. Although there are known techniques for solving this problem now (albeit with unwelcome side consequences), we should recall that the labour theory of value was initially motivated as an intuitively plausible theory of price. But when the connection between price and value is rendered as indirect as it is in the final theory, the intuitive motivation of the theory drains away. A further objection is that Marx’s assertion that only labour can create surplus value is unsupported by any argument or analysis, and can be argued to be merely an artifact of the nature of his presentation. Any commodity can be picked to play a similar role. Consequently with equal justification one could set out a corn theory of value, arguing that corn has the unique power of creating more value than it costs. Formally this would be identical to the labour theory of value. Nevertheless, the claims that somehow labour is responsible for the creation of value, and that profit is the consequence of exploitation, remain intuitively powerful, even if they are difficult to establish in detail.

However, even if the labour theory of value is considered discredited, there are elements of his theory that remain of worth. The Cambridge economist Joan Robinson, in An Essay on Marxian Economics , picked out two aspects of particular note. First, Marx’s refusal to accept that capitalism involves a harmony of interests between worker and capitalist, replacing this with a class based analysis of the worker’s struggle for better wages and conditions of work, versus the capitalist’s drive for ever greater profits. Second, Marx’s denial that there is any long-run tendency to equilibrium in the market, and his descriptions of mechanisms which underlie the trade-cycle of boom and bust. Both provide a salutary corrective to aspects of orthodox economic theory.

4. Theory of History

Marx did not set out his theory of history in great detail. Accordingly, it has to be constructed from a variety of texts, both those where he attempts to apply a theoretical analysis to past and future historical events, and those of a more purely theoretical nature. Of the latter, the 1859 Preface to A Critique of Political Economy has achieved canonical status. However, The German Ideology , co-written with Engels in 1845, is a vital early source in which Marx first sets out the basics of the outlook of historical materialism. We shall briefly outline both texts, and then look at the reconstruction of Marx’s theory of history in the hands of his philosophically most influential recent exponent, G.A. Cohen, who builds on the interpretation of the early Russian Marxist Plekhanov.

We should, however, be aware that Cohen’s interpretation is not universally accepted. Cohen provided his reconstruction of Marx partly because he was frustrated with existing Hegelian-inspired ‘dialectical’ interpretations of Marx, and what he considered to be the vagueness of the influential works of Louis Althusser, neither of which, he felt, provided a rigorous account of Marx’s views. However, some scholars believe that the interpretation that we shall focus on is faulty precisely for its lack of attention to the dialectic. One aspect of this criticism is that Cohen’s understanding has a surprisingly small role for the concept of class struggle, which is often felt to be central to Marx’s theory of history. Cohen’s explanation for this is that the 1859 Preface, on which his interpretation is based, does not give a prominent role to class struggle, and indeed it is not explicitly mentioned. Yet this reasoning is problematic for it is possible that Marx did not want to write in a manner that would engage the concerns of the police censor, and, indeed, a reader aware of the context may be able to detect an implicit reference to class struggle through the inclusion of such phrases as “then begins an era of social revolution,” and “the ideological forms in which men become conscious of this conflict and fight it out”. Hence it does not follow that Marx himself thought that the concept of class struggle was relatively unimportant. Furthermore, when A Critique of Political Economy was replaced by Capital , Marx made no attempt to keep the 1859 Preface in print, and its content is reproduced just as a very much abridged footnote in Capital . Nevertheless we shall concentrate here on Cohen’s interpretation as no other account has been set out with comparable rigour, precision and detail.

In The German Ideology Marx and Engels contrast their new materialist method with the idealism that had characterised previous German thought. Accordingly, they take pains to set out the ‘premises of the materialist method’. They start, they say, from ‘real human beings’, emphasising that human beings are essentially productive, in that they must produce their means of subsistence in order to satisfy their material needs. The satisfaction of needs engenders new needs of both a material and social kind, and forms of society arise corresponding to the state of development of human productive forces. Material life determines, or at least ‘conditions’ social life, and so the primary direction of social explanation is from material production to social forms, and thence to forms of consciousness. As the material means of production develop, ‘modes of co-operation’ or economic structures rise and fall, and eventually communism will become a real possibility once the plight of the workers and their awareness of an alternative motivates them sufficiently to become revolutionaries.

In the sketch of The German Ideology , all the key elements of historical materialism are present, even if the terminology is not yet that of Marx’s more mature writings. Marx’s statement in 1859 Preface renders much the same view in sharper form. Cohen’s reconstruction of Marx’s view in the Preface begins from what Cohen calls the Development Thesis, which is pre-supposed, rather than explicitly stated in the Preface. This is the thesis that the productive forces tend to develop, in the sense of becoming more powerful, over time. This states not that they always do develop, but that there is a tendency for them to do so. The productive forces are the means of production, together with productively applicable knowledge: technology, in other words. The next thesis is the primacy thesis, which has two aspects. The first states that the nature of the economic structure is explained by the level of development of the productive forces, and the second that the nature of the superstructure — the political and legal institutions of society— is explained by the nature of the economic structure. The nature of a society’s ideology, which is to say the religious, artistic, moral and philosophical beliefs contained within society, is also explained in terms of its economic structure, although this receives less emphasis in Cohen’s interpretation. Indeed many activities may well combine aspects of both the superstructure and ideology: a religion is constituted by both institutions and a set of beliefs.

Revolution and epoch change is understood as the consequence of an economic structure no longer being able to continue to develop the forces of production. At this point the development of the productive forces is said to be fettered, and, according to the theory once an economic structure fetters development it will be revolutionised — ‘burst asunder’ — and eventually replaced with an economic structure better suited to preside over the continued development of the forces of production.

In outline, then, the theory has a pleasing simplicity and power. It seems plausible that human productive power develops over time, and plausible too that economic structures exist for as long as they develop the productive forces, but will be replaced when they are no longer capable of doing this. Yet severe problems emerge when we attempt to put more flesh on these bones.

Prior to Cohen’s work, historical materialism had not been regarded as a coherent view within English-language political philosophy. The antipathy is well summed up with the closing words of H.B. Acton’s The Illusion of the Epoch : “Marxism is a philosophical farrago”. One difficulty taken particularly seriously by Cohen is an alleged inconsistency between the explanatory primacy of the forces of production, and certain claims made elsewhere by Marx which appear to give the economic structure primacy in explaining the development of the productive forces. For example, in The Communist Manifesto Marx states that: ‘The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionising the instruments of production.’ This appears to give causal and explanatory primacy to the economic structure — capitalism — which brings about the development of the forces of production. Cohen accepts that, on the surface at least, this generates a contradiction. Both the economic structure and the development of the productive forces seem to have explanatory priority over each other.

Unsatisfied by such vague resolutions as ‘determination in the last instance’, or the idea of ‘dialectical’ connections, Cohen self-consciously attempts to apply the standards of clarity and rigour of analytic philosophy to provide a reconstructed version of historical materialism.

The key theoretical innovation is to appeal to the notion of functional explanation (also sometimes called ‘consequence explanation’). The essential move is cheerfully to admit that the economic structure does indeed develop the productive forces, but to add that this, according to the theory, is precisely why we have capitalism (when we do). That is, if capitalism failed to develop the productive forces it would disappear. And, indeed, this fits beautifully with historical materialism. For Marx asserts that when an economic structure fails to develop the productive forces — when it ‘fetters’ the productive forces — it will be revolutionised and the epoch will change. So the idea of ‘fettering’ becomes the counterpart to the theory of functional explanation. Essentially fettering is what happens when the economic structure becomes dysfunctional.

Now it is apparent that this renders historical materialism consistent. Yet there is a question as to whether it is at too high a price. For we must ask whether functional explanation is a coherent methodological device. The problem is that we can ask what it is that makes it the case that an economic structure will only persist for as long as it develops the productive forces. Jon Elster has pressed this criticism against Cohen very hard. If we were to argue that there is an agent guiding history who has the purpose that the productive forces should be developed as much as possible then it would make sense that such an agent would intervene in history to carry out this purpose by selecting the economic structures which do the best job. However, it is clear that Marx makes no such metaphysical assumptions. Elster is very critical — sometimes of Marx, sometimes of Cohen — of the idea of appealing to ‘purposes’ in history without those being the purposes of anyone.

Cohen is well aware of this difficulty, but defends the use of functional explanation by comparing its use in historical materialism with its use in evolutionary biology. In contemporary biology it is commonplace to explain the existence of the stripes of a tiger, or the hollow bones of a bird, by pointing to the function of these features. Here we have apparent purposes which are not the purposes of anyone. The obvious counter, however, is that in evolutionary biology we can provide a causal story to underpin these functional explanations; a story involving chance variation and survival of the fittest. Therefore these functional explanations are sustained by a complex causal feedback loop in which dysfunctional elements tend to be filtered out in competition with better functioning elements. Cohen calls such background accounts ‘elaborations’ and he concedes that functional explanations are in need of elaborations. But he points out that standard causal explanations are equally in need of elaborations. We might, for example, be satisfied with the explanation that the vase broke because it was dropped on the floor, but a great deal of further information is needed to explain why this explanation works. Consequently, Cohen claims that we can be justified in offering a functional explanation even when we are in ignorance of its elaboration. Indeed, even in biology detailed causal elaborations of functional explanations have been available only relatively recently. Prior to Darwin, or arguably Lamark, the only candidate causal elaboration was to appeal to God’s purposes. Darwin outlined a very plausible mechanism, but having no genetic theory was not able to elaborate it into a detailed account. Our knowledge remains incomplete to this day. Nevertheless, it seems perfectly reasonable to say that birds have hollow bones in order to facilitate flight. Cohen’s point is that the weight of evidence that organisms are adapted to their environment would permit even a pre-Darwinian atheist to assert this functional explanation with justification. Hence one can be justified in offering a functional explanation even in absence of a candidate elaboration: if there is sufficient weight of inductive evidence.

At this point the issue, then, divides into a theoretical question and an empirical one. The empirical question is whether or not there is evidence that forms of society exist only for as long as they advance productive power, and are replaced by revolution when they fail. Here, one must admit, the empirical record is patchy at best, and there appear to have been long periods of stagnation, even regression, when dysfunctional economic structures were not revolutionised.

The theoretical issue is whether a plausible elaborating explanation is available to underpin Marxist functional explanations. Here there is something of a dilemma. In the first instance it is tempting to try to mimic the elaboration given in the Darwinian story, and appeal to chance variations and survival of the fittest. In this case ‘fittest’ would mean ‘most able to preside over the development of the productive forces’. Chance variation would be a matter of people trying out new types of economic relations. On this account new economic structures begin through experiment, but thrive and persist through their success in developing the productive forces. However the problem is that such an account would seem to introduce a larger element of contingency than Marx seeks, for it is essential to Marx’s thought that one should be able to predict the eventual arrival of communism. Within Darwinian theory there is no warrant for long-term predictions, for everything depends on the contingencies of particular situations. A similar heavy element of contingency would be inherited by a form of historical materialism developed by analogy with evolutionary biology. The dilemma, then, is that the best model for developing the theory makes predictions based on the theory unsound, yet the whole point of the theory is predictive. Hence one must either look for an alternative means of producing elaborating explanation, or give up the predictive ambitions of the theory.

The driving force of history, in Cohen’s reconstruction of Marx, is the development of the productive forces, the most important of which is technology. But what is it that drives such development? Ultimately, in Cohen’s account, it is human rationality. Human beings have the ingenuity to apply themselves to develop means to address the scarcity they find. This on the face of it seems very reasonable. Yet there are difficulties. As Cohen himself acknowledges, societies do not always do what would be rational for an individual to do. Co-ordination problems may stand in our way, and there may be structural barriers. Furthermore, it is relatively rare for those who introduce new technologies to be motivated by the need to address scarcity. Rather, under capitalism, the profit motive is the key. Of course it might be argued that this is the social form that the material need to address scarcity takes under capitalism. But still one may raise the question whether the need to address scarcity always has the influence that it appears to have taken on in modern times. For example, a ruling class’s absolute determination to hold on to power may have led to economically stagnant societies. Alternatively, it might be thought that a society may put religion or the protection of traditional ways of life ahead of economic needs. This goes to the heart of Marx’s theory that man is an essentially productive being and that the locus of interaction with the world is industry. As Cohen himself later argued in essays such as ‘Reconsidering Historical Materialism’, the emphasis on production may appear one-sided, and ignore other powerful elements in human nature. Such a criticism chimes with a criticism from the previous section; that the historical record may not, in fact, display the tendency to growth in the productive forces assumed by the theory.

Many defenders of Marx will argue that the problems stated are problems for Cohen’s interpretation of Marx, rather than for Marx himself. It is possible to argue, for example, that Marx did not have a general theory of history, but rather was a social scientist observing and encouraging the transformation of capitalism into communism as a singular event. And it is certainly true that when Marx analyses a particular historical episode, as he does in the 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon , any idea of fitting events into a fixed pattern of history seems very far from Marx’s mind. On other views Marx did have a general theory of history but it is far more flexible and less determinate than Cohen insists (Miller). And finally, as noted, there are critics who believe that Cohen’s interpretation is entirely wrong-headed (Sayers).

The issue of Marx and morality poses a conundrum. On reading Marx’s works at all periods of his life, there appears to be the strongest possible distaste towards bourgeois capitalist society, and an undoubted endorsement of future communist society. Yet the terms of this antipathy and endorsement are far from clear. Despite expectations, Marx never says that capitalism is unjust. Neither does he say that communism would be a just form of society. In fact he takes pains to distance himself from those who engage in a discourse of justice, and makes a conscious attempt to exclude direct moral commentary in his own works. The puzzle is why this should be, given the weight of indirect moral commentary one finds.

There are, initially, separate questions, concerning Marx’s attitude to capitalism and to communism. There are also separate questions concerning his attitude to ideas of justice, and to ideas of morality more broadly concerned. This, then, generates four questions: (1) Did Marx think capitalism unjust?; (2) did he think that capitalism could be morally criticised on other grounds?; (3) did he think that communism would be just? (4) did he think it could be morally approved of on other grounds? These are the questions we shall consider in this section.

The initial argument that Marx must have thought that capitalism is unjust is based on the observation that Marx argued that all capitalist profit is ultimately derived from the exploitation of the worker. Capitalism’s dirty secret is that it is not a realm of harmony and mutual benefit but a system in which one class systematically extracts profit from another. How could this fail to be unjust? Yet it is notable that Marx never concludes this, and in Capital he goes as far as to say that such exchange is ‘by no means an injustice’.

Allen Wood has argued that Marx took this approach because his general theoretical approach excludes any trans-epochal standpoint from which one can comment on the justice of an economic system. Even though one can criticize particular behaviour from within an economic structure as unjust (and theft under capitalism would be an example) it is not possible to criticise capitalism as a whole. This is a consequence of Marx’s analysis of the role of ideas of justice from within historical materialism. That is to say, juridical institutions are part of the superstructure, and ideas of justice are ideological, and the role of both the superstructure and ideology, in the functionalist reading of historical materialism adopted here, is to stabilise the economic structure. Consequently, to state that something is just under capitalism is simply a judgement applied to those elements of the system that will tend to have the effect of advancing capitalism. According to Marx, in any society the ruling ideas are those of the ruling class; the core of the theory of ideology.

Ziyad Husami, however, argues that Wood is mistaken, ignoring the fact that for Marx ideas undergo a double determination in that the ideas of the non-ruling class may be very different from those of the ruling class. Of course it is the ideas of the ruling class that receive attention and implementation, but this does not mean that other ideas do not exist. Husami goes as far as to argue that members of the proletariat under capitalism have an account of justice which matches communism. From this privileged standpoint of the proletariat, which is also Marx’s standpoint, capitalism is unjust, and so it follows that Marx thought capitalism unjust.

Plausible though it may sound, Husami’s argument fails to account for two related points. First, it cannot explain why Marx never described capitalism as unjust, and second, it does not account for the distance Marx wanted to place between his own scientific socialism, and that of the utopian socialists who argued for the injustice of capitalism. Hence one cannot avoid the conclusion that the ‘official’ view of Marx is that capitalism is not unjust.

Nevertheless, this leaves us with a puzzle. Much of Marx’s description of capitalism — his use of the words ‘embezzlement’, ‘robbery’ and ‘exploitation’ — belie the official account. Arguably, the only satisfactory way of understanding this issue is, once more, from G.A. Cohen, who proposes that Marx believed that capitalism was unjust, but did not believe that he believed it was unjust (Cohen 1983). In other words, Marx, like so many of us, did not have perfect knowledge of his own mind. In his explicit reflections on the justice of capitalism he was able to maintain his official view. But in less guarded moments his real view slips out, even if never in explicit language. Such an interpretation is bound to be controversial, but it makes good sense of the texts.

Whatever one concludes on the question of whether Marx thought capitalism unjust, it is, nevertheless, obvious that Marx thought that capitalism was not the best way for human beings to live. Points made in his early writings remain present throughout his writings, if no longer connected to an explicit theory of alienation. The worker finds work a torment, suffers poverty, overwork and lack of fulfillment and freedom. People do not relate to each other as humans should.

Does this amount to a moral criticism of capitalism or not? In the absence of any special reason to argue otherwise, it simply seems obvious that Marx’s critique is a moral one. Capitalism impedes human flourishing.

Marx, though, once more refrained from making this explicit; he seemed to show no interest in locating his criticism of capitalism in any of the traditions of moral philosophy, or explaining how he was generating a new tradition. There may have been two reasons for his caution. The first was that while there were bad things about capitalism, there is, from a world historical point of view, much good about it too. For without capitalism, communism would not be possible. Capitalism is to be transcended, not abolished, and this may be difficult to convey in the terms of moral philosophy.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, we need to return to the contrast between scientific and utopian socialism. The utopians appealed to universal ideas of truth and justice to defend their proposed schemes, and their theory of transition was based on the idea that appealing to moral sensibilities would be the best, perhaps only, way of bringing about the new chosen society. Marx wanted to distance himself from this tradition of utopian thought, and the key point of distinction was to argue that the route to understanding the possibilities of human emancipation lay in the analysis of historical and social forces, not in morality. Hence, for Marx, any appeal to morality was theoretically a backward step.

This leads us now to Marx’s assessment of communism. Would communism be a just society? In considering Marx’s attitude to communism and justice there are really only two viable possibilities: either he thought that communism would be a just society or he thought that the concept of justice would not apply: that communism would transcend justice.

Communism is described by Marx, in the Critique of the Gotha Programme , as a society in which each person should contribute according to their ability and receive according to their need. This certainly sounds like a theory of justice, and could be adopted as such. However it is possibly truer to Marx’s thought to say that this is part of an account in which communism transcends justice, as Lukes has argued.

If we start with the idea that the point of ideas of justice is to resolve disputes, then a society without disputes would have no need or place for justice. We can see this by reflecting upon Hume’s idea of the circumstances of justice. Hume argued that if there was enormous material abundance — if everyone could have whatever they wanted without invading another’s share — we would never have devised rules of justice. And, of course, Marx often suggested that communism would be a society of such abundance. But Hume also suggested that justice would not be needed in other circumstances; if there were complete fellow-feeling between all human beings. Again there would be no conflict and no need for justice. Of course, one can argue whether either material abundance or human fellow-feeling to this degree would be possible, but the point is that both arguments give a clear sense in which communism transcends justice.

Nevertheless we remain with the question of whether Marx thought that communism could be commended on other moral grounds. On a broad understanding, in which morality, or perhaps better to say ethics, is concerning with the idea of living well, it seems that communism can be assessed favourably in this light. One compelling argument is that Marx’s career simply makes no sense unless we can attribute such a belief to him. But beyond this we can be brief in that the considerations adduced in section 2 above apply again. Communism clearly advances human flourishing, in Marx’s view. The only reason for denying that, in Marx’s vision, it would amount to a good society is a theoretical antipathy to the word ‘good’. And here the main point is that, in Marx’s view, communism would not be brought about by high-minded benefactors of humanity. Quite possibly his determination to retain this point of difference between himself and the Utopian socialists led him to disparage the importance of morality to a degree that goes beyond the call of theoretical necessity.

Primary Literature

- Marx, Karl and Friedrich Engels, Gesamtausgabe (MEGA), Berlin, 1975–.

- –––, Collected Works , New York and London: International Publishers. 1975.

- –––, Selected Works , 2 Volumes, Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1962.

- Marx, Karl, Karl Marx: Selected Writings , 2 nd edition, David McLellan (ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Secondary Literature

See McLellan 1973 and Wheen 1999 for biographies of Marx, and see Singer 2000 and Wolff 2002 for general introductions.

- Acton, H.B., 1955, The Illusion of the Epoch , London: Cohen and West.

- Althusser, Louis, 1969, For Marx , London: Penguin.

- Althusser, Louis, and Balibar, Etienne, 1970, Reading Capital , London: NLB.

- Arthur, C.J., 1986, Dialectics of Labour , Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Avineri, Shlomo, 1970, The Social and Political Thought of Karl Marx , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bottomore, Tom (ed.), 1979, Karl Marx , Oxford: Blackwell.

- Brudney, Daniel, 1998, Marx’s Attempt to Leave Philosophy . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Carver, Terrell, 1982, Marx’s Social Theory , New York: Oxford University Press.

- Carver, Terrell (ed.), 1991, The Cambridge Companion to Marx , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Carver, Terrell, 1998, The Post-Modern Marx , Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Cohen, Joshua, 1982, ‘Review of G.A. Cohen, Karl Marx’s Theory of History ’, Journal of Philosophy , 79: 253–273.

- Cohen, G.A., 1983, ‘Review of Allen Wood, Karl Marx ’, Mind , 92: 440–445.

- Cohen, G.A., 1988, History, Labour and Freedom , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cohen, G.A., 2001, Karl Marx’s Theory of History: A Defence , 2nd edition, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- Desai, Megnad, 2002, Marx’s Revenge , London: Verso.

- Elster, Jon, 1985, Making Sense of Marx, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Geras, Norman, 1989, ‘The Controversy about Marx and Justice,’ in A. Callinicos (ed.), Marxist Theory , Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Hook, Sidney, 1950, From Hegel to Marx , New York: Humanities Press.

- Husami, Ziyad, 1978, ‘Marx on Distributive Justice’, Philosophy and Public Affairs , 8: 27–64.

- Kamenka, Eugene, 1962, The Ethical Foundations of Marxism London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Kolakowski, Leszek, 1978, Main Currents of Marxism , 3 volumes, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Leopold, David, 2007, The Young Karl Marx , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lukes, Stephen, 1987, Marxism and Morality , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Maguire, John, 1972, Marx’s Paris Writings , Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

- McLellan, David, 1970, Marx Before Marxism , London: Macmillan.

- McLellan, David, 1973, Karl Marx: His Life and Thought , London: Macmillan.

- Miller, Richard, 1984, Analyzing Marx , Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Peffer, Rodney, 1990, Marxism, Morality and Social Justice , Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Plekhanov, G.V., (1947 [1895]), The Development of the Monist View of History London: Lawrence and Wishart.

- Robinson, Joan, 1942, An Essay on Marxian Economics , London: Macmillan.

- Roemer, John, 1982, A General Theory of Exploitation and Class , Cambridge Ma.: Harvard University Press.

- Roemer, John (ed.), 1986, Analytical Marxism , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rosen, Michael, 1996, On Voluntary Servitude , Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Sayers, Sean, 1990, ‘Marxism and the Dialectical Method: A Critique of G.A. Cohen’, in S.Sayers (ed.), Socialism, Feminism and Philosophy: A Radical Philosophy Reader , London: Routledge.

- Singer, Peter, 2000, Marx: A Very Short Introduction , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sober, E., Levine, A., and Wright, E.O. 1992, Reconstructing Marx , London: Verso.

- Sweezy, Paul, 1942 [1970], The Theory of Capitalist Development , New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Wheen, Francis, 1999, Karl Marx , London: Fourth Estate.

- Wolff, Jonathan, 2002, Why Read Marx Today? , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wolff, Robert Paul, 1984, Understanding Marx , Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Wood, Allen, 1981, Karl Marx , London: Routledge; second edition, 2004.

- Wood, Allen, 1972, ‘The Marxian Critique of Justice’, Philosophy and Public Affairs , 1: 244–82.

How to cite this entry . Preview the PDF version of this entry at the Friends of the SEP Society . Look up this entry topic at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project (InPhO). Enhanced bibliography for this entry at PhilPapers , with links to its database.

- Marxists Internet Archive

Bauer, Bruno | Feuerbach, Ludwig Andreas | Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich | history, philosophy of

Copyright © 2017 by Jonathan Wolff < jonathan . wolff @ bsg . ox . ac . uk >

Support SEP

Mirror sites.

View this site from another server:

- Info about mirror sites

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is copyright © 2016 by The Metaphysics Research Lab , Center for the Study of Language and Information (CSLI), Stanford University

Library of Congress Catalog Data: ISSN 1095-5054

Karl Marx: his philosophy explained

Tutor in Philosophy and Sociology, Deakin University

Disclosure statement

Christopher Pollard does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Deakin University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

In 1845, Karl Marx declared : “philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it”.

Change it he did.

Political movements representing masses of new industrial workers, many inspired by his thought, reshaped the world in the 19th and 20th centuries through revolution and reform. His work influenced unions, labour parties and social democratic parties, and helped spark revolution via communist parties in Europe and beyond.

Around the world, “Marxist” governments were formed, who claimed to be committed to his principles, and who upheld dogmatic versions of his thought as part of their official doctrine.

Marx’s thought was groundbreaking. It came to stimulate arguments in every major language, in philosophy, history, politics and economics. It even helped to found the discipline of sociology.

Although his influence in the social sciences and humanities is not what it once was, his work continues to help theorists make sense of the complex social structures that shape our lives.

Read more: Explainer: the ideas of Foucault

Marx was writing when mid-Victorian capitalism was at its Dickensian worst, analysing how the new industrialism was causing radical social upheaval and severe urban poverty. Of his many writings, perhaps the most well known and influential are the rather large Capital Volume 1 (1867) and the very small Communist Manifesto (1848), penned with his collaborator Frederick Engels.

On economics alone, he made important observations that influenced our understanding of the role of boom/bust cycles, the link between market competition and rapid technological advances, and the tendency of markets towards concentration and monopolies.

Marx also made prescient observations regarding what we now call “ globalisation ”. He emphasised “the newly created connections […] of the world market” and the important role of international trade.

At the time, property owners held the vast majority of wealth, and their wealth rapidly accumulated through the creation of factories.

The labour of the workers – the property-less masses – was bought and sold like any other commodity. The workers toiled for starvation wages, as “appendages of the machine[s]”, in Marx’s famous phrase. By holding them in this position, the owners grew ever richer, siphoning off the value created by this labour.

This would inevitably lead to militant international political organisation in response.

It is from this we get Marx’s famous call in 1848, the year of Europe-wide revolutions:

workers of the world unite!

To do philosophy properly, Marx thought, we have to form theories that capture the concrete details of real people’s lives – to make theory fully grounded in practice.

His primary interest wasn’t simply capitalism. It was human existence and our potential.

His enduring philosophical contribution is an insightful, historically grounded perspective on human beings and industrial society.

Marx observed capitalism wasn’t only an economic system by which we produced food, clothing and shelter; it was also bound up with a system of social relations.

Work structured people’s lives and opportunities in different ways depending on their role in the production process: most people were either part of the “owning class” or “working class”. The interests of these classes were fundamentally opposed, which led inevitably to conflict between them.

On the basis of this, Marx predicted the inevitable collapse of capitalism leading to equally inevitable working-class revolutions. However, he seriously underestimated capitalism’s adaptability. In particular, the way that parliamentary democracy and the welfare state could moderate the excesses and instabilities of the economic system.

Marx argued social change is driven by the tension created within an existing social order through technological and organisational innovations in production.

Technology-driven changes in production make new social forms possible, such that old social forms and classes become outmoded and displaced by new ones. Once, the dominant class were the land owning lords. But the new industrial system produced a new dominant class: the capitalists.

Against the philosophical trend to view human beings as simply organic machines, Marx saw us as a creative and productive type of being. Humanity uses these capacities to transform the natural world. However, in doing this we also, throughout history, transform ourselves in the process. This makes human life distinct from that of other animals.

The conditions under which people live deeply shape the way they see and understand the world. As Marx put it:

men make their own history [but] they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves.

Marx viewed human history as process of people progressively overcoming impediments to self-understanding and freedom. These impediments can be mental, material and institutional. He believed philosophy could offer ways we might realise our human potential in the world.

Theories, he said, were not just about “interpreting the world”, but “changing it”.

Individuals and groups are situated in social contexts inherited from the past which limit what they can do – but these social contexts afford us certain possibilities.

The present political situation that confronts us and the scope for actions we might take to improve it, is the result of our being situated in our unique place and time in history.

This approach has influenced thinkers across traditions and continents to better understand the complexities of the social and political world, and to think more concretely about prospects for change.

On the basis of his historical approach, Marx argued inequality is not a natural fact; it is socially created. He sought to show how economic systems such as feudalism or capitalism – despite being hugely complex historical developments – were ultimately our own creations.

Read more: Explainer: Nietzsche, nihilism and reasons to be cheerful

Alienation and freedom

By seeing the economic system and what it produces as objective and independent of humanity, this system comes to dominate us. When systematic exploitation is viewed as a product of the “natural order”, humans are, from a philosophical perspective, “enslaved” by their own creation.

What we have produced comes to be viewed as alien to us. Marx called this process “alienation”.

Despite having intrinsic creative capacities, most of humanity experience themselves as stifled by the conditions in which they work and live. They are alienated a) in the production process (“what” is produced and “how”); b) from others (with whom they constantly compete); and c) from their own creative potential.

For Marx, human beings intrinsically strive toward freedom, and we are not really free unless we control our own destiny.

Marx believed a rational social order could realise our human capacities as individuals as well as collectively, overcoming political and economic inequalities.

Writing in a period before workers could even vote (as voting was restricted to landowning males) Marx argued “the full and free development of every individual” – along with meaningful participation in the decisions that shaped their lives – would be realised through the creation of a “classless society [of] the free and equal”.

Marx’s concept of ideology introduced an innovative way to critique how dominant beliefs and practices – commonly taken to be for the good of all – actually reflect the interests and reinforce the power of the “ruling” class.

For Marx, beliefs in philosophy, culture and economics often function to rationalise unfair advantages and privileges as “natural” when, in fact, the amount of change we see in history shows they are not.

He was not saying this is a conspiracy of the ruling class, where those in the dominant class believe things simply because they reinforce the present power structure.

Rather, it is because people are raised and learn how to think within a given social order. Through this, the views that seem eminently rational rather conveniently tend to uphold the distribution of power and wealth as they are.

Marx had always aspired to be a philosopher, but was unable to pursue it as a profession because his views were judged too radical for a university post in his native Prussia. Instead, he earned his living as a crusading journalist.

By any account, Marx was a giant of modern thought.

His influence was so far reaching that people are often unaware just how much his ideas have shaped their own thinking.

Compliance Lead

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Marx's Political Thought

Introduction.

- Selections of Marx’s Early Writings

- Selections of Marx’s Mature Writings

- Biographies of Marx

- Introductory Overviews of Marx’s Thought

- More Substantial Studies of Marx’s Thought

- Classical Marxist Developments of Marxism

- The Present as a Historical Problem: Historical Materialism

- Studies of Marx’s Critique of Political Economy

- Applying Marx’s Critique of Political Economy

- Overviews of Marx’s Politics

- Marx’s Political Practice

- The State Form

- Social Class

- Environmental Politics

- Trade Unionism

- Engagements with Liberal Political Philosophy: Marx’s Ethics

- Freedom, Alienation, and Human Nature

- Imperialism and Colonialism

- Marxism and Nationalism

- Women’s Oppression: From Classical Marxism to Second Wave Feminism

- Marxism and Women’s Oppression: Contemporary Contributions

- Theorizing Racism

- Marxism and Religion

- Studies of Engels’s Thought

- Theorizing Stalinism

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Aristotle's Political Thought

- Hegel's Political Thought

- Hobbes’s Political Thought

- Hume’s Political Thought

- Liberal Pluralism

- Machiavelli’s Political Thought

- Politics of Class Formation

- Rousseau’s Political Thought

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Cross-National Surveys of Public Opinion

- Politics of School Reform

- Ratification of the Constitution

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Marx's Political Thought by Paul Blackledge LAST REVIEWED: 26 May 2016 LAST MODIFIED: 26 May 2016 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756223-0171

Karl Marx (b. 1818–d. 1883) is undoubtedly one of the most important and influential thinkers of the modern period. Nevertheless, although much of what he wrote has been sedimented into contemporary culture, many of his ideas, especially his political ideas, are far too scandalous ever to be fully incorporated into academic common sense. Part of the reason for this is that his legacy has consistently been attacked and misrepresented by individuals and groups who are, so to speak, on the other side of the barricades. At a much more interesting level, however, academic incomprehension of Marx’s thought is rooted in a structural gap between his totalizing methodology and academia’s tendency to fragment along disciplinary and sub-disciplinary lines. It is because Marx’s thought marks a profound break with this standpoint that any serious attempt to map his ideas onto the categories of modern academic thought will be fraught with dangers. Indeed, the deeply historical and revolutionary character of Marx’s thought makes it almost unintelligible from the essentially static perspective of modern theory. It is not that modern theory does not recognize change; it is rather that it tends to conceive it in effectively reformist terms: change is fixed within boundaries set by more-or-less naturalized capitalist social relations. Any attempt to write a study of Marx’s supposed political theory must therefore confront the problem that his thought cannot be fully incorporated within this standpoint. He was neither an economist nor a sociologist nor a political theorist, but his revolutionary theory involves the sublation of these (and more) categories into a greater whole. Consequently, though Marx’s thought can be said to have economic, political, and sociological, etc., dimensions, it cannot be reduced to an amalgam of these approaches, and critics should be wary of Procrustean attempts to fit aspects of his work into one or other academic sub-discipline, or indeed to reduce his conception of totality to a form of inter- or multi-disciplinarity. Specifically, whereas modern political theory tends to treat politics as a universal characteristic of human communities, Marx insists that it is a historical science: states, ideology, and law are aspects of broader superstructural relations that function to fix and reproduce minority rule within class-divided societies. Politics, from this perspective, is best understood as an epiphenomenon of the relations of production by which one class maintains its control over humanity’s productive interaction with nature: it has a beginning with the emergence of class societies, hopefully an end with what Marx calls the communist closure of humanity’s “pre-history,” and can only properly be understood by those involved in the struggle to overcome the conditions of its existence.

There are numerous Marxist journals available in the Anglophone world, each catering in differing degrees to academic and activist audiences from perspectives rooted in Marx’s legacy. The oldest continuously published journal on the English-speaking Marxist left is Science and Society , which was launched at the height of the “Popular Front” in 1936. Just over a decade later Monthly Review was launched in much less propitious circumstances at the beginning of the Cold War—and its editors faced the wrath of McCarthyism in the 1950s. Both journals were and continue to be open and independent vehicles of debate and analysis on the Marxist left. New Left Review , International Socialism , New Politics and Socialist Register were launched at the time of the British and American New Lefts at the turn of the 1960s and have continued publication as distinctive voices on the left long after the collapse of the movement that gave them life. Critique and Capital and Class came into being more than a decade later to cater to a new audience of ex-students who had been radicalized in the 1960s and subsequently moved into the academy. As the left went on the defensive in the 1980s, new journals such Capitalism Nature Socialism , Rethinking Marxism , Socialism and Democracy , and Studies in Marxism were launched to response to the crisis of Marxism as both social democracy and Stalinism retreated before neoliberal capitalism. More recently, since its launch in 1997 Historical Materialism has become an important voice on the academic Marxist left.

Capital & Class .

Launched in 1977 by the Conference of Socialist Economists in the United Kingdom. The initial focus of Capital and Class was, as its title suggests, on economic issues. Subsequently, however, it has expanded its remit to include articles on all aspects of Marxist theory.

Capitalism Nature Socialism .

Launched in 1988 by academics and activists in California, Capitalism Nature Socialism reflected a growing awareness that the emerging environmental crisis was a capitalist phenomenon best understood in terms drawn from but also extending Marx’s critique of political economy.

Launched in 1973 by Hillel Ticktin and others around him at Glasgow University, Critique is renowned for its analysis of Stalinism as a new and dysfunctional form of class rule and capitalism as an endemically crisis-prone system.

Historical Materialism .

Launched in 1997 by British activists and academics many of whom were affiliated with the Socialist Workers Party, Historical Materialism was intended to be, and has largely succeeded in becoming, the leading Anglophone forum for debate and theoretical innovation on the academic Marxist left.

International Socialism .

Launched in 1960 International Socialism was initially associated with a heterodox Trotskyist attempt by Tony Cliff and Michael Kidron to reorient the revolutionary left to the new postwar realities through, most importantly, their writings on Soviet state capitalism, the permanent arms economy as an explanation for the postwar boom, and “deflected permanent revolution” in the Third World. It has subsequently continued its focus on raising theory to the level of revolutionary practice and is linked to the British Socialist Workers Party.