- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Definition, Format, Examples, and Tips

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

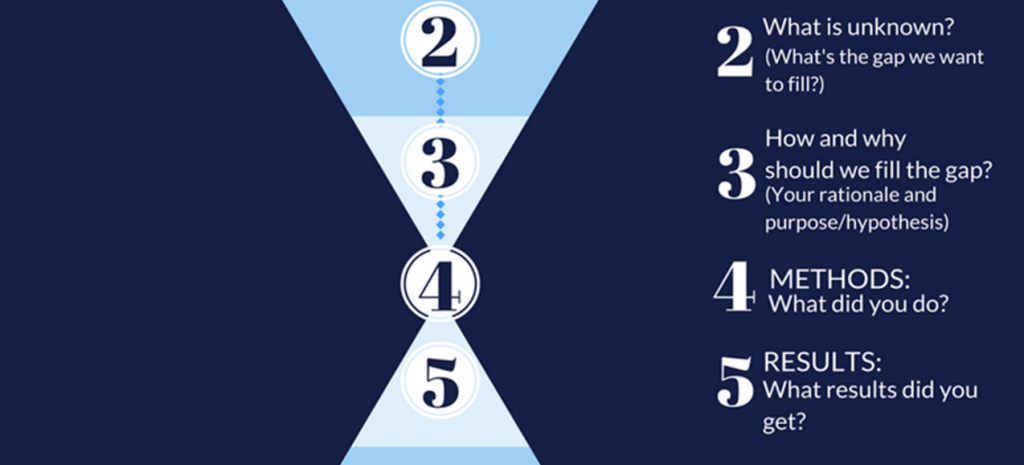

- The Scientific Method

Hypothesis Format

Falsifiability of a hypothesis.

- Operationalization

Hypothesis Types

Hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

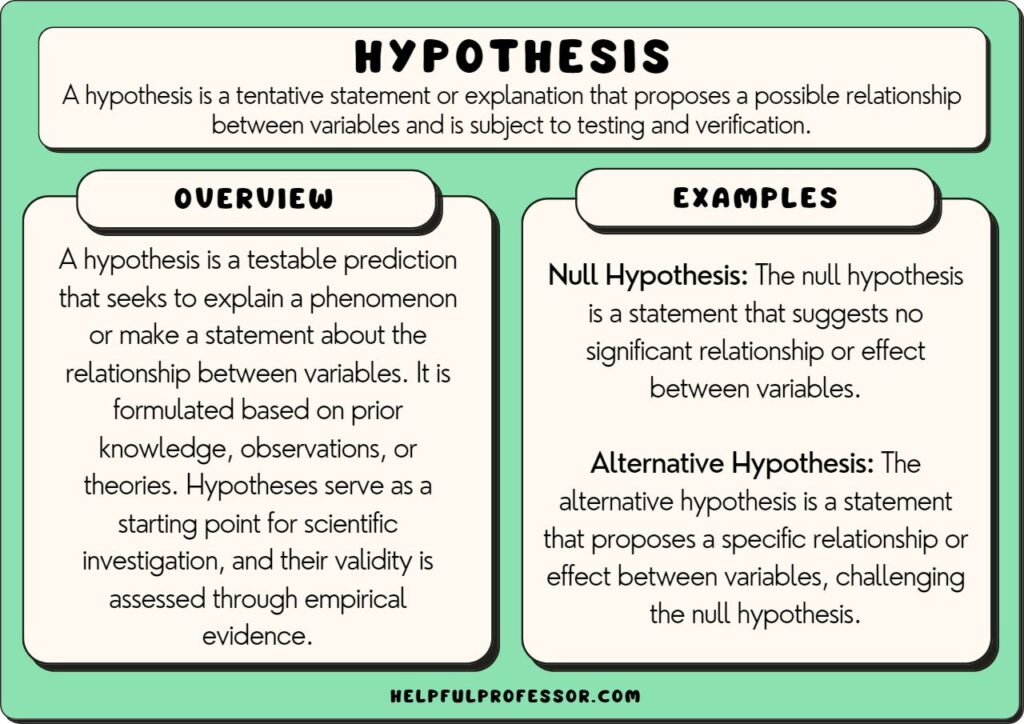

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. It is a preliminary answer to your question that helps guide the research process.

Consider a study designed to examine the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance. The hypothesis might be: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

At a Glance

A hypothesis is crucial to scientific research because it offers a clear direction for what the researchers are looking to find. This allows them to design experiments to test their predictions and add to our scientific knowledge about the world. This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. At this point, researchers then begin to develop a testable hypothesis.

Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.

In a study exploring the effects of a particular drug, the hypothesis might be that researchers expect the drug to have some type of effect on the symptoms of a specific illness. In psychology, the hypothesis might focus on how a certain aspect of the environment might influence a particular behavior.

Remember, a hypothesis does not have to be correct. While the hypothesis predicts what the researchers expect to see, the goal of the research is to determine whether this guess is right or wrong. When conducting an experiment, researchers might explore numerous factors to determine which ones might contribute to the ultimate outcome.

In many cases, researchers may find that the results of an experiment do not support the original hypothesis. When writing up these results, the researchers might suggest other options that should be explored in future studies.

In many cases, researchers might draw a hypothesis from a specific theory or build on previous research. For example, prior research has shown that stress can impact the immune system. So a researcher might hypothesize: "People with high-stress levels will be more likely to contract a common cold after being exposed to the virus than people who have low-stress levels."

In other instances, researchers might look at commonly held beliefs or folk wisdom. "Birds of a feather flock together" is one example of folk adage that a psychologist might try to investigate. The researcher might pose a specific hypothesis that "People tend to select romantic partners who are similar to them in interests and educational level."

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

So how do you write a good hypothesis? When trying to come up with a hypothesis for your research or experiments, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is your hypothesis based on your research on a topic?

- Can your hypothesis be tested?

- Does your hypothesis include independent and dependent variables?

Before you come up with a specific hypothesis, spend some time doing background research. Once you have completed a literature review, start thinking about potential questions you still have. Pay attention to the discussion section in the journal articles you read . Many authors will suggest questions that still need to be explored.

How to Formulate a Good Hypothesis

To form a hypothesis, you should take these steps:

- Collect as many observations about a topic or problem as you can.

- Evaluate these observations and look for possible causes of the problem.

- Create a list of possible explanations that you might want to explore.

- After you have developed some possible hypotheses, think of ways that you could confirm or disprove each hypothesis through experimentation. This is known as falsifiability.

In the scientific method , falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.

Students sometimes confuse the idea of falsifiability with the idea that it means that something is false, which is not the case. What falsifiability means is that if something was false, then it is possible to demonstrate that it is false.

One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is that it makes claims that cannot be refuted or proven false.

The Importance of Operational Definitions

A variable is a factor or element that can be changed and manipulated in ways that are observable and measurable. However, the researcher must also define how the variable will be manipulated and measured in the study.

Operational definitions are specific definitions for all relevant factors in a study. This process helps make vague or ambiguous concepts detailed and measurable.

For example, a researcher might operationally define the variable " test anxiety " as the results of a self-report measure of anxiety experienced during an exam. A "study habits" variable might be defined by the amount of studying that actually occurs as measured by time.

These precise descriptions are important because many things can be measured in various ways. Clearly defining these variables and how they are measured helps ensure that other researchers can replicate your results.

Replicability

One of the basic principles of any type of scientific research is that the results must be replicable.

Replication means repeating an experiment in the same way to produce the same results. By clearly detailing the specifics of how the variables were measured and manipulated, other researchers can better understand the results and repeat the study if needed.

Some variables are more difficult than others to define. For example, how would you operationally define a variable such as aggression ? For obvious ethical reasons, researchers cannot create a situation in which a person behaves aggressively toward others.

To measure this variable, the researcher must devise a measurement that assesses aggressive behavior without harming others. The researcher might utilize a simulated task to measure aggressiveness in this situation.

Hypothesis Checklist

- Does your hypothesis focus on something that you can actually test?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate the variables?

- Can your hypothesis be tested without violating ethical standards?

The hypothesis you use will depend on what you are investigating and hoping to find. Some of the main types of hypotheses that you might use include:

- Simple hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.

- Complex hypothesis : This type suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent and dependent variables.

- Null hypothesis : This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

- Alternative hypothesis : This hypothesis states the opposite of the null hypothesis.

- Statistical hypothesis : This hypothesis uses statistical analysis to evaluate a representative population sample and then generalizes the findings to the larger group.

- Logical hypothesis : This hypothesis assumes a relationship between variables without collecting data or evidence.

A hypothesis often follows a basic format of "If {this happens} then {this will happen}." One way to structure your hypothesis is to describe what will happen to the dependent variable if you change the independent variable .

The basic format might be: "If {these changes are made to a certain independent variable}, then we will observe {a change in a specific dependent variable}."

A few examples of simple hypotheses:

- "Students who eat breakfast will perform better on a math exam than students who do not eat breakfast."

- "Students who experience test anxiety before an English exam will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety."

- "Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone."

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will have higher reading scores than students who do not receive the intervention."

Examples of a complex hypothesis include:

- "People with high-sugar diets and sedentary activity levels are more likely to develop depression."

- "Younger people who are regularly exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces."

Examples of a null hypothesis include:

- "There is no difference in anxiety levels between people who take St. John's wort supplements and those who do not."

- "There is no difference in scores on a memory recall task between children and adults."

- "There is no difference in aggression levels between children who play first-person shooter games and those who do not."

Examples of an alternative hypothesis:

- "People who take St. John's wort supplements will have less anxiety than those who do not."

- "Adults will perform better on a memory task than children."

- "Children who play first-person shooter games will show higher levels of aggression than children who do not."

Collecting Data on Your Hypothesis

Once a researcher has formed a testable hypothesis, the next step is to select a research design and start collecting data. The research method depends largely on exactly what they are studying. There are two basic types of research methods: descriptive research and experimental research.

Descriptive Research Methods

Descriptive research such as case studies , naturalistic observations , and surveys are often used when conducting an experiment is difficult or impossible. These methods are best used to describe different aspects of a behavior or psychological phenomenon.

Once a researcher has collected data using descriptive methods, a correlational study can examine how the variables are related. This research method might be used to investigate a hypothesis that is difficult to test experimentally.

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental methods are used to demonstrate causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, the researcher systematically manipulates a variable of interest (known as the independent variable) and measures the effect on another variable (known as the dependent variable).

Unlike correlational studies, which can only be used to determine if there is a relationship between two variables, experimental methods can be used to determine the actual nature of the relationship—whether changes in one variable actually cause another to change.

The hypothesis is a critical part of any scientific exploration. It represents what researchers expect to find in a study or experiment. In situations where the hypothesis is unsupported by the research, the research still has value. Such research helps us better understand how different aspects of the natural world relate to one another. It also helps us develop new hypotheses that can then be tested in the future.

Thompson WH, Skau S. On the scope of scientific hypotheses . R Soc Open Sci . 2023;10(8):230607. doi:10.1098/rsos.230607

Taran S, Adhikari NKJ, Fan E. Falsifiability in medicine: what clinicians can learn from Karl Popper [published correction appears in Intensive Care Med. 2021 Jun 17;:]. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1007/s00134-021-06432-z

Eyler AA. Research Methods for Public Health . 1st ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2020. doi:10.1891/9780826182067.0004

Nosek BA, Errington TM. What is replication ? PLoS Biol . 2020;18(3):e3000691. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000691

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies . Perspect Clin Res . 2019;10(1):34-36. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_154_18

Nevid J. Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Wadworth, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

6 Hypothesis Examples in Psychology

The hypothesis is one of the most important steps of psychological research. Hypothesis refers to an assumption or the temporary statement made by the researcher before the execution of the experiment, regarding the possible outcome of that experiment. A hypothesis can be tested through various scientific and statistical tools. It is a logical guess based on previous knowledge and investigations related to the problem under investigation. In this article, we’ll learn about the significance of the hypothesis, the sources of the hypothesis, and the various examples of the hypothesis.

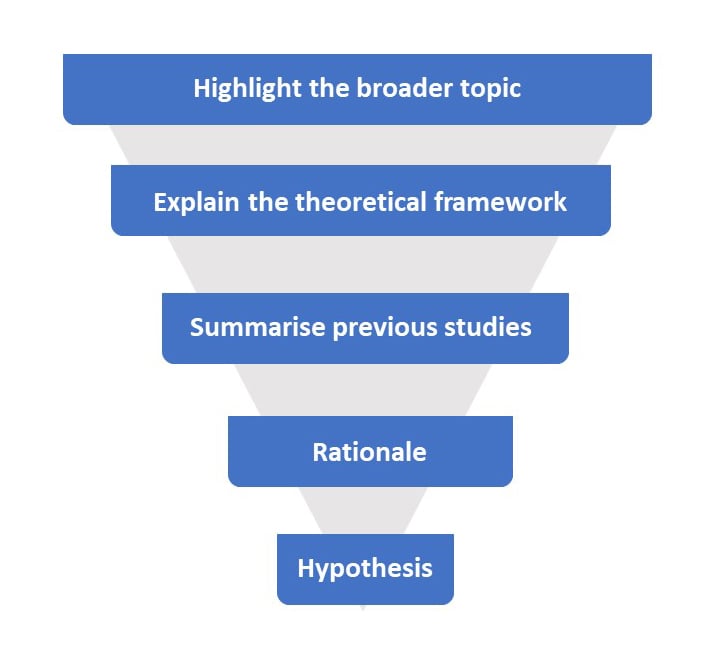

Sources of Hypothesis

The formulation of a good hypothesis is not an easy task. One needs to take care of the various crucial steps to get an accurate hypothesis. The hypothesis formulation demands both the creativity of the researcher and his/her years of experience. The researcher needs to use critical thinking to avoid committing any errors such as choosing the wrong hypothesis. Although the hypothesis is considered the first step before further investigations such as data collection for the experiment, the hypothesis formulation also requires some amount of data collection. The data collection for the hypothesis formulation refers to the review of literature related to the concerned topic, and understanding of the previous research on the related topic. Following are some of the main sources of the hypothesis that may help the researcher to formulate a good hypothesis.

- Reviewing the similar studies and literature related to a similar problem.

- Examining the available data concerned with the problem.

- Discussing the problem with the colleagues, or the professional researchers about the problem under investigation.

- Thorough research and investigation by conducting field interviews or surveys on the people that are directly concerned with the problem under investigation.

- Sometimes ‘institution’ of the well known and experienced researcher is also considered as a good source of the hypothesis formulation.

Real Life Hypothesis Examples

1. null hypothesis and alternative hypothesis examples.

Every research problem-solving procedure begins with the formulation of the null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis. The alternative hypothesis assumes the existence of the relationship between the variables under study, while the null hypothesis denies the relationship between the variables under study. Following are examples of the null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis based on the research problem.

Research Problem: What is the benefit of eating an apple daily on your health?

Alternative Hypothesis: Eating an apple daily reduces the chances of visiting the doctor.

Null Hypothesis : Eating an apple daily does not impact the frequency of visiting the doctor.

Research Problem: What is the impact of spending a lot of time on mobiles on the attention span of teenagers.

Alternative Problem: Spending time on the mobiles and attention span have a negative correlation.

Null Hypothesis: There does not exist any correlation between the use of mobile by teenagers on their attention span.

Research Problem: What is the impact of providing flexible working hours to the employees on the job satisfaction level.

Alternative Hypothesis : Employees who get the option of flexible working hours have better job satisfaction than the employees who don’t get the option of flexible working hours.

Null Hypothesis: There is no association between providing flexible working hours and job satisfaction.

2. Simple Hypothesis Examples

The hypothesis that includes only one independent variable (predictor variable) and one dependent variable (outcome variable) is termed the simple hypothesis. For example, the children are more likely to get clinical depression if their parents had also suffered from the clinical depression. Here, the independent variable is the parents suffering from clinical depression and the dependent or the outcome variable is the clinical depression observed in their child/children. Other examples of the simple hypothesis are given below,

- If the management provides the official snack breaks to the employees, the employees are less likely to take the off-site breaks. Here, providing snack breaks is the independent variable and the employees are less likely to take the off-site break is the dependent variable.

3. Complex Hypothesis Examples

If the hypothesis includes more than one independent (predictor variable) or more than one dependent variable (outcome variable) it is known as the complex hypothesis. For example, clinical depression in children is associated with a family clinical depression history and a stressful and hectic lifestyle. In this case, there are two independent variables, i.e., family history of clinical depression and hectic and stressful lifestyle, and one dependent variable, i.e., clinical depression. Following are some more examples of the complex hypothesis,

4. Logical Hypothesis Examples

If there are not many pieces of evidence and studies related to the concerned problem, then the researcher can take the help of the general logic to formulate the hypothesis. The logical hypothesis is proved true through various logic. For example, if the researcher wants to prove that the animal needs water for its survival, then this can be logically verified through the logic that ‘living beings can not survive without the water.’ Following are some more examples of logical hypotheses,

- Tia is not good at maths, hence she will not choose the accounting sector as her career.

- If there is a correlation between skin cancer and ultraviolet rays, then the people who are more exposed to the ultraviolet rays are more prone to skin cancer.

- The beings belonging to the different planets can not breathe in the earth’s atmosphere.

- The creatures living in the sea use anaerobic respiration as those living outside the sea use aerobic respiration.

5. Empirical Hypothesis Examples

The empirical hypothesis comes into existence when the statement is being tested by conducting various experiments. This hypothesis is not just an idea or notion, instead, it refers to the statement that undergoes various trials and errors, and various extraneous variables can impact the result. The trials and errors provide a set of results that can be testable over time. Following are the examples of the empirical hypothesis,

- The hungry cat will quickly reach the endpoint through the maze, if food is placed at the endpoint then the cat is not hungry.

- The people who consume vitamin c have more glowing skin than the people who consume vitamin E.

- Hair growth is faster after the consumption of Vitamin E than vitamin K.

- Plants will grow faster with fertilizer X than with fertilizer Y.

6. Statistical Hypothesis Examples

The statements that can be proven true by using the various statistical tools are considered the statistical hypothesis. The researcher uses statistical data about an area or the group in the analysis of the statistical hypothesis. For example, if you study the IQ level of the women belonging to nation X, it would be practically impossible to measure the IQ level of each woman belonging to nation X. Here, statistical methods come to the rescue. The researcher can choose the sample population, i.e., women belonging to the different states or provinces of the nation X, and conduct the statistical tests on this sample population to get the average IQ of the women belonging to the nation X. Following are the examples of the statistical hypothesis.

- 30 per cent of the women belonging to the nation X are working.

- 50 per cent of the people living in the savannah are above the age of 70 years.

- 45 per cent of the poor people in the United States are uneducated.

Significance of Hypothesis

A hypothesis is very crucial in experimental research as it aims to predict any particular outcome of the experiment. Hypothesis plays an important role in guiding the researchers to focus on the concerned area of research only. However, the hypothesis is not required by all researchers. The type of research that seeks for finding facts, i.e., historical research, does not need the formulation of the hypothesis. In the historical research, the researchers look for the pieces of evidence related to the human life, the history of a particular area, or the occurrence of any event, this means that the researcher does not have a strong basis to make an assumption in these types of researches, hence hypothesis is not needed in this case. As stated by Hillway (1964)

When fact-finding alone is the aim of the study, a hypothesis is not required.”

The hypothesis may not be an important part of the descriptive or historical studies, but it is a crucial part for the experimental researchers. Following are some of the points that show the importance of formulating a hypothesis before conducting the experiment.

- Hypothesis provides a tentative statement about the outcome of the experiment that can be validated and tested. It helps the researcher to directly focus on the problem under investigation by collecting the relevant data according to the variables mentioned in the hypothesis.

- Hypothesis facilitates a direction to the experimental research. It helps the researcher in analysing what is relevant for the study and what’s not. It prevents the researcher’s time as he does not need to waste time on reviewing the irrelevant research and literature, and also prevents the researcher from collecting the irrelevant data.

- Hypothesis helps the researcher in choosing the appropriate sample, statistical tests to conduct, variables to be studied and the research methodology. The hypothesis also helps the study from being generalised as it focuses on the limited and exact problem under investigation.

- Hypothesis act as a framework for deducing the outcomes of the experiment. The researcher can easily test the different hypotheses for understanding the interaction among the various variables involved in the study. On this basis of the results obtained from the testing of various hypotheses, the researcher can formulate the final meaningful report.

Related Posts

17 Monopoly Examples in Real Life

12 Conflict Theory Examples in Real Life

Cognitive Bias Examples

22 Altruism Examples in Animals

7 Real Life Examples Of Deontology

10 Examples of Esteem Needs (Maslow’s Hierarchy)

Add comment cancel reply.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes .

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more variables . An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls. A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Step 1: ask a question.

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

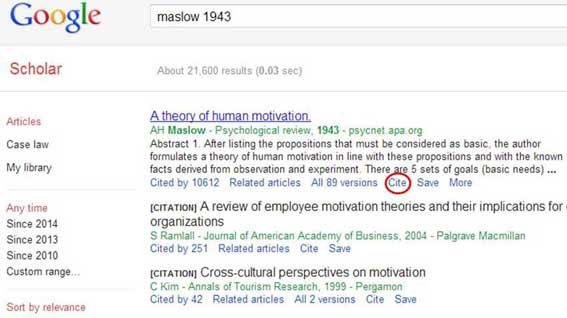

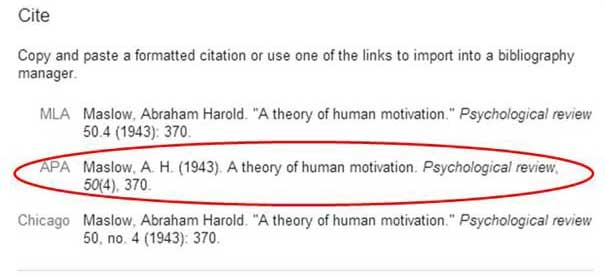

Step 2: Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalise more complex constructs.

Step 3: Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

Step 4: Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

Step 5: Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if … then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

Step 6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

A hypothesis is not just a guess. It should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (‘ x affects y because …’).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses. In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, May 06). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 13 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/hypothesis-writing/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, operationalisation | a guide with examples, pros & cons, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples.

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Research Hypothesis: Good & Bad Examples

What is a research hypothesis?

A research hypothesis is an attempt at explaining a phenomenon or the relationships between phenomena/variables in the real world. Hypotheses are sometimes called “educated guesses”, but they are in fact (or let’s say they should be) based on previous observations, existing theories, scientific evidence, and logic. A research hypothesis is also not a prediction—rather, predictions are ( should be) based on clearly formulated hypotheses. For example, “We tested the hypothesis that KLF2 knockout mice would show deficiencies in heart development” is an assumption or prediction, not a hypothesis.

The research hypothesis at the basis of this prediction is “the product of the KLF2 gene is involved in the development of the cardiovascular system in mice”—and this hypothesis is probably (hopefully) based on a clear observation, such as that mice with low levels of Kruppel-like factor 2 (which KLF2 codes for) seem to have heart problems. From this hypothesis, you can derive the idea that a mouse in which this particular gene does not function cannot develop a normal cardiovascular system, and then make the prediction that we started with.

What is the difference between a hypothesis and a prediction?

You might think that these are very subtle differences, and you will certainly come across many publications that do not contain an actual hypothesis or do not make these distinctions correctly. But considering that the formulation and testing of hypotheses is an integral part of the scientific method, it is good to be aware of the concepts underlying this approach. The two hallmarks of a scientific hypothesis are falsifiability (an evaluation standard that was introduced by the philosopher of science Karl Popper in 1934) and testability —if you cannot use experiments or data to decide whether an idea is true or false, then it is not a hypothesis (or at least a very bad one).

So, in a nutshell, you (1) look at existing evidence/theories, (2) come up with a hypothesis, (3) make a prediction that allows you to (4) design an experiment or data analysis to test it, and (5) come to a conclusion. Of course, not all studies have hypotheses (there is also exploratory or hypothesis-generating research), and you do not necessarily have to state your hypothesis as such in your paper.

But for the sake of understanding the principles of the scientific method, let’s first take a closer look at the different types of hypotheses that research articles refer to and then give you a step-by-step guide for how to formulate a strong hypothesis for your own paper.

Types of Research Hypotheses

Hypotheses can be simple , which means they describe the relationship between one single independent variable (the one you observe variations in or plan to manipulate) and one single dependent variable (the one you expect to be affected by the variations/manipulation). If there are more variables on either side, you are dealing with a complex hypothesis. You can also distinguish hypotheses according to the kind of relationship between the variables you are interested in (e.g., causal or associative ). But apart from these variations, we are usually interested in what is called the “alternative hypothesis” and, in contrast to that, the “null hypothesis”. If you think these two should be listed the other way round, then you are right, logically speaking—the alternative should surely come second. However, since this is the hypothesis we (as researchers) are usually interested in, let’s start from there.

Alternative Hypothesis

If you predict a relationship between two variables in your study, then the research hypothesis that you formulate to describe that relationship is your alternative hypothesis (usually H1 in statistical terms). The goal of your hypothesis testing is thus to demonstrate that there is sufficient evidence that supports the alternative hypothesis, rather than evidence for the possibility that there is no such relationship. The alternative hypothesis is usually the research hypothesis of a study and is based on the literature, previous observations, and widely known theories.

Null Hypothesis

The hypothesis that describes the other possible outcome, that is, that your variables are not related, is the null hypothesis ( H0 ). Based on your findings, you choose between the two hypotheses—usually that means that if your prediction was correct, you reject the null hypothesis and accept the alternative. Make sure, however, that you are not getting lost at this step of the thinking process: If your prediction is that there will be no difference or change, then you are trying to find support for the null hypothesis and reject H1.

Directional Hypothesis

While the null hypothesis is obviously “static”, the alternative hypothesis can specify a direction for the observed relationship between variables—for example, that mice with higher expression levels of a certain protein are more active than those with lower levels. This is then called a one-tailed hypothesis.

Another example for a directional one-tailed alternative hypothesis would be that

H1: Attending private classes before important exams has a positive effect on performance.

Your null hypothesis would then be that

H0: Attending private classes before important exams has no/a negative effect on performance.

Nondirectional Hypothesis

A nondirectional hypothesis does not specify the direction of the potentially observed effect, only that there is a relationship between the studied variables—this is called a two-tailed hypothesis. For instance, if you are studying a new drug that has shown some effects on pathways involved in a certain condition (e.g., anxiety) in vitro in the lab, but you can’t say for sure whether it will have the same effects in an animal model or maybe induce other/side effects that you can’t predict and potentially increase anxiety levels instead, you could state the two hypotheses like this:

H1: The only lab-tested drug (somehow) affects anxiety levels in an anxiety mouse model.

You then test this nondirectional alternative hypothesis against the null hypothesis:

H0: The only lab-tested drug has no effect on anxiety levels in an anxiety mouse model.

How to Write a Hypothesis for a Research Paper

Now that we understand the important distinctions between different kinds of research hypotheses, let’s look at a simple process of how to write a hypothesis.

Writing a Hypothesis Step:1

Ask a question, based on earlier research. Research always starts with a question, but one that takes into account what is already known about a topic or phenomenon. For example, if you are interested in whether people who have pets are happier than those who don’t, do a literature search and find out what has already been demonstrated. You will probably realize that yes, there is quite a bit of research that shows a relationship between happiness and owning a pet—and even studies that show that owning a dog is more beneficial than owning a cat ! Let’s say you are so intrigued by this finding that you wonder:

What is it that makes dog owners even happier than cat owners?

Let’s move on to Step 2 and find an answer to that question.

Writing a Hypothesis Step 2:

Formulate a strong hypothesis by answering your own question. Again, you don’t want to make things up, take unicorns into account, or repeat/ignore what has already been done. Looking at the dog-vs-cat papers your literature search returned, you see that most studies are based on self-report questionnaires on personality traits, mental health, and life satisfaction. What you don’t find is any data on actual (mental or physical) health measures, and no experiments. You therefore decide to make a bold claim come up with the carefully thought-through hypothesis that it’s maybe the lifestyle of the dog owners, which includes walking their dog several times per day, engaging in fun and healthy activities such as agility competitions, and taking them on trips, that gives them that extra boost in happiness. You could therefore answer your question in the following way:

Dog owners are happier than cat owners because of the dog-related activities they engage in.

Now you have to verify that your hypothesis fulfills the two requirements we introduced at the beginning of this resource article: falsifiability and testability . If it can’t be wrong and can’t be tested, it’s not a hypothesis. We are lucky, however, because yes, we can test whether owning a dog but not engaging in any of those activities leads to lower levels of happiness or well-being than owning a dog and playing and running around with them or taking them on trips.

Writing a Hypothesis Step 3:

Make your predictions and define your variables. We have verified that we can test our hypothesis, but now we have to define all the relevant variables, design our experiment or data analysis, and make precise predictions. You could, for example, decide to study dog owners (not surprising at this point), let them fill in questionnaires about their lifestyle as well as their life satisfaction (as other studies did), and then compare two groups of active and inactive dog owners. Alternatively, if you want to go beyond the data that earlier studies produced and analyzed and directly manipulate the activity level of your dog owners to study the effect of that manipulation, you could invite them to your lab, select groups of participants with similar lifestyles, make them change their lifestyle (e.g., couch potato dog owners start agility classes, very active ones have to refrain from any fun activities for a certain period of time) and assess their happiness levels before and after the intervention. In both cases, your independent variable would be “ level of engagement in fun activities with dog” and your dependent variable would be happiness or well-being .

Examples of a Good and Bad Hypothesis

Let’s look at a few examples of good and bad hypotheses to get you started.

Good Hypothesis Examples

Bad hypothesis examples, tips for writing a research hypothesis.

If you understood the distinction between a hypothesis and a prediction we made at the beginning of this article, then you will have no problem formulating your hypotheses and predictions correctly. To refresh your memory: We have to (1) look at existing evidence, (2) come up with a hypothesis, (3) make a prediction, and (4) design an experiment. For example, you could summarize your dog/happiness study like this:

(1) While research suggests that dog owners are happier than cat owners, there are no reports on what factors drive this difference. (2) We hypothesized that it is the fun activities that many dog owners (but very few cat owners) engage in with their pets that increases their happiness levels. (3) We thus predicted that preventing very active dog owners from engaging in such activities for some time and making very inactive dog owners take up such activities would lead to an increase and decrease in their overall self-ratings of happiness, respectively. (4) To test this, we invited dog owners into our lab, assessed their mental and emotional well-being through questionnaires, and then assigned them to an “active” and an “inactive” group, depending on…

Note that you use “we hypothesize” only for your hypothesis, not for your experimental prediction, and “would” or “if – then” only for your prediction, not your hypothesis. A hypothesis that states that something “would” affect something else sounds as if you don’t have enough confidence to make a clear statement—in which case you can’t expect your readers to believe in your research either. Write in the present tense, don’t use modal verbs that express varying degrees of certainty (such as may, might, or could ), and remember that you are not drawing a conclusion while trying not to exaggerate but making a clear statement that you then, in a way, try to disprove . And if that happens, that is not something to fear but an important part of the scientific process.

Similarly, don’t use “we hypothesize” when you explain the implications of your research or make predictions in the conclusion section of your manuscript, since these are clearly not hypotheses in the true sense of the word. As we said earlier, you will find that many authors of academic articles do not seem to care too much about these rather subtle distinctions, but thinking very clearly about your own research will not only help you write better but also ensure that even that infamous Reviewer 2 will find fewer reasons to nitpick about your manuscript.

Perfect Your Manuscript With Professional Editing

Now that you know how to write a strong research hypothesis for your research paper, you might be interested in our free AI proofreader , Wordvice AI, which finds and fixes errors in grammar, punctuation, and word choice in academic texts. Or if you are interested in human proofreading , check out our English editing services , including research paper editing and manuscript editing .

On the Wordvice academic resources website , you can also find many more articles and other resources that can help you with writing the other parts of your research paper , with making a research paper outline before you put everything together, or with writing an effective cover letter once you are ready to submit.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Developing a Hypothesis

Rajiv S. Jhangiani; I-Chant A. Chiang; Carrie Cuttler; and Dana C. Leighton

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis.

- Discover how theories are used to generate hypotheses and how the results of studies can be used to further inform theories.

- Understand the characteristics of a good hypothesis.

Theories and Hypotheses

Before describing how to develop a hypothesis, it is important to distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis. A theory is a coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena. Although theories can take a variety of forms, one thing they have in common is that they go beyond the phenomena they explain by including variables, structures, processes, functions, or organizing principles that have not been observed directly. Consider, for example, Zajonc’s theory of social facilitation and social inhibition (1965) [1] . He proposed that being watched by others while performing a task creates a general state of physiological arousal, which increases the likelihood of the dominant (most likely) response. So for highly practiced tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make correct responses, but for relatively unpracticed tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make incorrect responses. Notice that this theory—which has come to be called drive theory—provides an explanation of both social facilitation and social inhibition that goes beyond the phenomena themselves by including concepts such as “arousal” and “dominant response,” along with processes such as the effect of arousal on the dominant response.

Outside of science, referring to an idea as a theory often implies that it is untested—perhaps no more than a wild guess. In science, however, the term theory has no such implication. A theory is simply an explanation or interpretation of a set of phenomena. It can be untested, but it can also be extensively tested, well supported, and accepted as an accurate description of the world by the scientific community. The theory of evolution by natural selection, for example, is a theory because it is an explanation of the diversity of life on earth—not because it is untested or unsupported by scientific research. On the contrary, the evidence for this theory is overwhelmingly positive and nearly all scientists accept its basic assumptions as accurate. Similarly, the “germ theory” of disease is a theory because it is an explanation of the origin of various diseases, not because there is any doubt that many diseases are caused by microorganisms that infect the body.

A hypothesis , on the other hand, is a specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate. It is an explanation that relies on just a few key concepts. Hypotheses are often specific predictions about what will happen in a particular study. They are developed by considering existing evidence and using reasoning to infer what will happen in the specific context of interest. Hypotheses are often but not always derived from theories. So a hypothesis is often a prediction based on a theory but some hypotheses are a-theoretical and only after a set of observations have been made, is a theory developed. This is because theories are broad in nature and they explain larger bodies of data. So if our research question is really original then we may need to collect some data and make some observations before we can develop a broader theory.

Theories and hypotheses always have this if-then relationship. “ If drive theory is correct, then cockroaches should run through a straight runway faster, and a branching runway more slowly, when other cockroaches are present.” Although hypotheses are usually expressed as statements, they can always be rephrased as questions. “Do cockroaches run through a straight runway faster when other cockroaches are present?” Thus deriving hypotheses from theories is an excellent way of generating interesting research questions.

But how do researchers derive hypotheses from theories? One way is to generate a research question using the techniques discussed in this chapter and then ask whether any theory implies an answer to that question. For example, you might wonder whether expressive writing about positive experiences improves health as much as expressive writing about traumatic experiences. Although this question is an interesting one on its own, you might then ask whether the habituation theory—the idea that expressive writing causes people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings—implies an answer. In this case, it seems clear that if the habituation theory is correct, then expressive writing about positive experiences should not be effective because it would not cause people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings. A second way to derive hypotheses from theories is to focus on some component of the theory that has not yet been directly observed. For example, a researcher could focus on the process of habituation—perhaps hypothesizing that people should show fewer signs of emotional distress with each new writing session.

Among the very best hypotheses are those that distinguish between competing theories. For example, Norbert Schwarz and his colleagues considered two theories of how people make judgments about themselves, such as how assertive they are (Schwarz et al., 1991) [2] . Both theories held that such judgments are based on relevant examples that people bring to mind. However, one theory was that people base their judgments on the number of examples they bring to mind and the other was that people base their judgments on how easily they bring those examples to mind. To test these theories, the researchers asked people to recall either six times when they were assertive (which is easy for most people) or 12 times (which is difficult for most people). Then they asked them to judge their own assertiveness. Note that the number-of-examples theory implies that people who recalled 12 examples should judge themselves to be more assertive because they recalled more examples, but the ease-of-examples theory implies that participants who recalled six examples should judge themselves as more assertive because recalling the examples was easier. Thus the two theories made opposite predictions so that only one of the predictions could be confirmed. The surprising result was that participants who recalled fewer examples judged themselves to be more assertive—providing particularly convincing evidence in favor of the ease-of-retrieval theory over the number-of-examples theory.

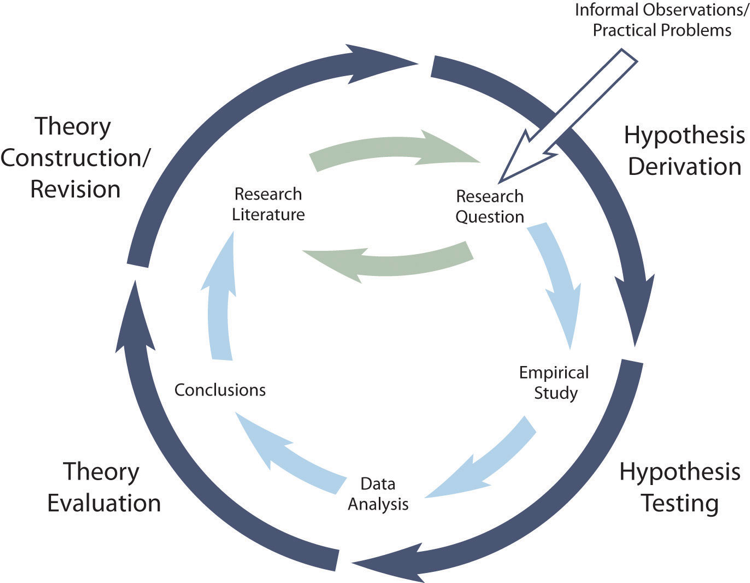

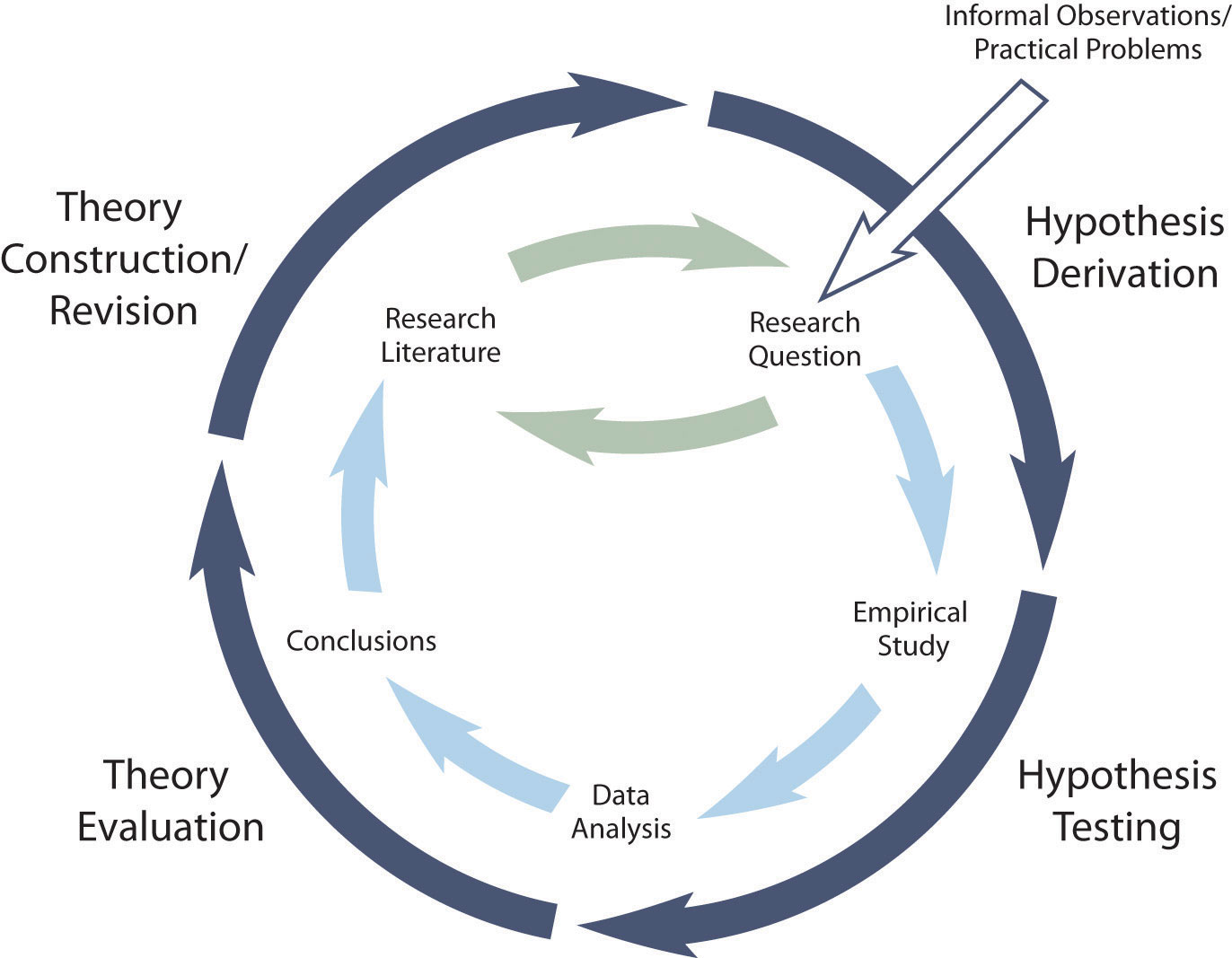

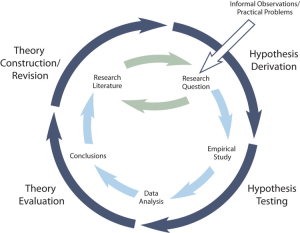

Theory Testing

The primary way that scientific researchers use theories is sometimes called the hypothetico-deductive method (although this term is much more likely to be used by philosophers of science than by scientists themselves). Researchers begin with a set of phenomena and either construct a theory to explain or interpret them or choose an existing theory to work with. They then make a prediction about some new phenomenon that should be observed if the theory is correct. Again, this prediction is called a hypothesis. The researchers then conduct an empirical study to test the hypothesis. Finally, they reevaluate the theory in light of the new results and revise it if necessary. This process is usually conceptualized as a cycle because the researchers can then derive a new hypothesis from the revised theory, conduct a new empirical study to test the hypothesis, and so on. As Figure 2.3 shows, this approach meshes nicely with the model of scientific research in psychology presented earlier in the textbook—creating a more detailed model of “theoretically motivated” or “theory-driven” research.

As an example, let us consider Zajonc’s research on social facilitation and inhibition. He started with a somewhat contradictory pattern of results from the research literature. He then constructed his drive theory, according to which being watched by others while performing a task causes physiological arousal, which increases an organism’s tendency to make the dominant response. This theory predicts social facilitation for well-learned tasks and social inhibition for poorly learned tasks. He now had a theory that organized previous results in a meaningful way—but he still needed to test it. He hypothesized that if his theory was correct, he should observe that the presence of others improves performance in a simple laboratory task but inhibits performance in a difficult version of the very same laboratory task. To test this hypothesis, one of the studies he conducted used cockroaches as subjects (Zajonc, Heingartner, & Herman, 1969) [3] . The cockroaches ran either down a straight runway (an easy task for a cockroach) or through a cross-shaped maze (a difficult task for a cockroach) to escape into a dark chamber when a light was shined on them. They did this either while alone or in the presence of other cockroaches in clear plastic “audience boxes.” Zajonc found that cockroaches in the straight runway reached their goal more quickly in the presence of other cockroaches, but cockroaches in the cross-shaped maze reached their goal more slowly when they were in the presence of other cockroaches. Thus he confirmed his hypothesis and provided support for his drive theory. (Zajonc also showed that drive theory existed in humans [Zajonc & Sales, 1966] [4] in many other studies afterward).

Incorporating Theory into Your Research

When you write your research report or plan your presentation, be aware that there are two basic ways that researchers usually include theory. The first is to raise a research question, answer that question by conducting a new study, and then offer one or more theories (usually more) to explain or interpret the results. This format works well for applied research questions and for research questions that existing theories do not address. The second way is to describe one or more existing theories, derive a hypothesis from one of those theories, test the hypothesis in a new study, and finally reevaluate the theory. This format works well when there is an existing theory that addresses the research question—especially if the resulting hypothesis is surprising or conflicts with a hypothesis derived from a different theory.

To use theories in your research will not only give you guidance in coming up with experiment ideas and possible projects, but it lends legitimacy to your work. Psychologists have been interested in a variety of human behaviors and have developed many theories along the way. Using established theories will help you break new ground as a researcher, not limit you from developing your own ideas.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

There are three general characteristics of a good hypothesis. First, a good hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable . We must be able to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and if you’ll recall Popper’s falsifiability criterion, it must be possible to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false. Second, a good hypothesis must be logical. As described above, hypotheses are more than just a random guess. Hypotheses should be informed by previous theories or observations and logical reasoning. Typically, we begin with a broad and general theory and use deductive reasoning to generate a more specific hypothesis to test based on that theory. Occasionally, however, when there is no theory to inform our hypothesis, we use inductive reasoning which involves using specific observations or research findings to form a more general hypothesis. Finally, the hypothesis should be positive. That is, the hypothesis should make a positive statement about the existence of a relationship or effect, rather than a statement that a relationship or effect does not exist. As scientists, we don’t set out to show that relationships do not exist or that effects do not occur so our hypotheses should not be worded in a way to suggest that an effect or relationship does not exist. The nature of science is to assume that something does not exist and then seek to find evidence to prove this wrong, to show that it really does exist. That may seem backward to you but that is the nature of the scientific method. The underlying reason for this is beyond the scope of this chapter but it has to do with statistical theory.

- Zajonc, R. B. (1965). Social facilitation. Science, 149 , 269–274 ↵

- Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61 , 195–202. ↵

- Zajonc, R. B., Heingartner, A., & Herman, E. M. (1969). Social enhancement and impairment of performance in the cockroach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13 , 83–92. ↵

- Zajonc, R.B. & Sales, S.M. (1966). Social facilitation of dominant and subordinate responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2 , 160-168. ↵

A coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena.

A specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate.

A cyclical process of theory development, starting with an observed phenomenon, then developing or using a theory to make a specific prediction of what should happen if that theory is correct, testing that prediction, refining the theory in light of the findings, and using that refined theory to develop new hypotheses, and so on.

The ability to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and the possibility to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false.

Developing a Hypothesis Copyright © by Rajiv S. Jhangiani; I-Chant A. Chiang; Carrie Cuttler; and Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Manuscript Preparation

What is and How to Write a Good Hypothesis in Research?

- 4 minute read

- 311.5K views

Table of Contents

One of the most important aspects of conducting research is constructing a strong hypothesis. But what makes a hypothesis in research effective? In this article, we’ll look at the difference between a hypothesis and a research question, as well as the elements of a good hypothesis in research. We’ll also include some examples of effective hypotheses, and what pitfalls to avoid.

What is a Hypothesis in Research?

Simply put, a hypothesis is a research question that also includes the predicted or expected result of the research. Without a hypothesis, there can be no basis for a scientific or research experiment. As such, it is critical that you carefully construct your hypothesis by being deliberate and thorough, even before you set pen to paper. Unless your hypothesis is clearly and carefully constructed, any flaw can have an adverse, and even grave, effect on the quality of your experiment and its subsequent results.

Research Question vs Hypothesis

It’s easy to confuse research questions with hypotheses, and vice versa. While they’re both critical to the Scientific Method, they have very specific differences. Primarily, a research question, just like a hypothesis, is focused and concise. But a hypothesis includes a prediction based on the proposed research, and is designed to forecast the relationship of and between two (or more) variables. Research questions are open-ended, and invite debate and discussion, while hypotheses are closed, e.g. “The relationship between A and B will be C.”

A hypothesis is generally used if your research topic is fairly well established, and you are relatively certain about the relationship between the variables that will be presented in your research. Since a hypothesis is ideally suited for experimental studies, it will, by its very existence, affect the design of your experiment. The research question is typically used for new topics that have not yet been researched extensively. Here, the relationship between different variables is less known. There is no prediction made, but there may be variables explored. The research question can be casual in nature, simply trying to understand if a relationship even exists, descriptive or comparative.

How to Write Hypothesis in Research

Writing an effective hypothesis starts before you even begin to type. Like any task, preparation is key, so you start first by conducting research yourself, and reading all you can about the topic that you plan to research. From there, you’ll gain the knowledge you need to understand where your focus within the topic will lie.

Remember that a hypothesis is a prediction of the relationship that exists between two or more variables. Your job is to write a hypothesis, and design the research, to “prove” whether or not your prediction is correct. A common pitfall is to use judgments that are subjective and inappropriate for the construction of a hypothesis. It’s important to keep the focus and language of your hypothesis objective.

An effective hypothesis in research is clearly and concisely written, and any terms or definitions clarified and defined. Specific language must also be used to avoid any generalities or assumptions.

Use the following points as a checklist to evaluate the effectiveness of your research hypothesis:

- Predicts the relationship and outcome

- Simple and concise – avoid wordiness

- Clear with no ambiguity or assumptions about the readers’ knowledge

- Observable and testable results

- Relevant and specific to the research question or problem

Research Hypothesis Example

Perhaps the best way to evaluate whether or not your hypothesis is effective is to compare it to those of your colleagues in the field. There is no need to reinvent the wheel when it comes to writing a powerful research hypothesis. As you’re reading and preparing your hypothesis, you’ll also read other hypotheses. These can help guide you on what works, and what doesn’t, when it comes to writing a strong research hypothesis.

Here are a few generic examples to get you started.

Eating an apple each day, after the age of 60, will result in a reduction of frequency of physician visits.

Budget airlines are more likely to receive more customer complaints. A budget airline is defined as an airline that offers lower fares and fewer amenities than a traditional full-service airline. (Note that the term “budget airline” is included in the hypothesis.

Workplaces that offer flexible working hours report higher levels of employee job satisfaction than workplaces with fixed hours.

Each of the above examples are specific, observable and measurable, and the statement of prediction can be verified or shown to be false by utilizing standard experimental practices. It should be noted, however, that often your hypothesis will change as your research progresses.

Language Editing Plus

Elsevier’s Language Editing Plus service can help ensure that your research hypothesis is well-designed, and articulates your research and conclusions. Our most comprehensive editing package, you can count on a thorough language review by native-English speakers who are PhDs or PhD candidates. We’ll check for effective logic and flow of your manuscript, as well as document formatting for your chosen journal, reference checks, and much more.

- Research Process

Systematic Literature Review or Literature Review?

What is a Problem Statement? [with examples]

You may also like.

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

The Essentials of Writing to Communicate Research in Medicine

Changing Lines: Sentence Patterns in Academic Writing

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Chapter 4: Theory in Psychology

4.3 using theories in psychological research, learning objectives.

- Explain how researchers in psychology test their theories, and give a concrete example.

- Explain how psychologists reevaluate theories in light of new results, including some of the complications involved.

- Describe several ways to incorporate theory into your own research.

We have now seen what theories are, what they are for, and the variety of forms that they take in psychological research. In this section we look more closely at how researchers actually use them. We begin with a general description of how researchers test and revise their theories, and we end with some practical advice for beginning researchers who want to incorporate theory into their research.

Theory Testing and Revision

The primary way that scientific researchers use theories is sometimes called the hypothetico-deductive method (although this term is much more likely to be used by philosophers of science than by scientists themselves). A researcher begins with a set of phenomena and either constructs a theory to explain or interpret them or chooses an existing theory to work with. He or she then makes a prediction about some new phenomenon that should be observed if the theory is correct. Again, this prediction is called a hypothesis. The researcher then conducts an empirical study to test the hypothesis. Finally, he or she reevaluates the theory in light of the new results and revises it if necessary. This process is usually conceptualized as a cycle because the researcher can then derive a new hypothesis from the revised theory, conduct a new empirical study to test the hypothesis, and so on. As Figure 4.5 “Hypothetico-Deductive Method Combined With the General Model of Scientific Research in Psychology” shows, this approach meshes nicely with the model of scientific research in psychology presented earlier in the book—creating a more detailed model of “theoretically motivated” or “theory-driven” research.

Figure 4.5 Hypothetico-Deductive Method Combined With the General Model of Scientific Research in Psychology

Together they form a model of theoretically motivated research.

As an example, let us return to Zajonc’s research on social facilitation and inhibition. He started with a somewhat contradictory pattern of results from the research literature. He then constructed his drive theory, according to which being watched by others while performing a task causes physiological arousal, which increases an organism’s tendency to make the dominant response. This leads to social facilitation for well-learned tasks and social inhibition for poorly learned tasks. He now had a theory that organized previous results in a meaningful way—but he still needed to test it. He hypothesized that if his theory was correct, he should observe that the presence of others improves performance in a simple laboratory task but inhibits performance in a difficult version of the very same laboratory task. To test this hypothesis, one of the studies he conducted used cockroaches as subjects (Zajonc, Heingartner, & Herman, 1969). The cockroaches ran either down a straight runway (an easy task for a cockroach) or through a cross-shaped maze (a difficult task for a cockroach) to escape into a dark chamber when a light was shined on them. They did this either while alone or in the presence of other cockroaches in clear plastic “audience boxes.” Zajonc found that cockroaches in the straight runway reached their goal more quickly in the presence of other cockroaches, but cockroaches in the cross-shaped maze reached their goal more slowly when they were in the presence of other cockroaches. Thus he confirmed his hypothesis and provided support for his drive theory.

Constructing or Choosing a Theory

Along with generating research questions, constructing theories is one of the more creative parts of scientific research. But as with all creative activities, success requires preparation and hard work more than anything else. To construct a good theory, a researcher must know in detail about the phenomena of interest and about any existing theories based on a thorough review of the literature. The new theory must provide a coherent explanation or interpretation of the phenomena of interest and have some advantage over existing theories. It could be more formal and therefore more precise, broader in scope, more parsimonious, or it could take a new perspective or theoretical approach. If there is no existing theory, then almost any theory can be a step in the right direction.

As we have seen, formality, scope, and theoretical approach are determined in part by the nature of the phenomena to be interpreted. But the researcher’s interests and abilities play a role too. For example, constructing a theory that specifies the neural structures and processes underlying a set of phenomena requires specialized knowledge and experience in neuroscience (which most professional researchers would acquire in college and then graduate school). But again, many theories in psychology are relatively informal, narrow in scope, and expressed in terms that even a beginning researcher can understand and even use to construct his or her own new theory.

It is probably more common, however, for a researcher to start with a theory that was originally constructed by someone else—giving due credit to the originator of the theory. This is another example of how researchers work collectively to advance scientific knowledge. Once they have identified an existing theory, they might derive a hypothesis from the theory and test it or modify the theory to account for some new phenomenon and then test the modified theory.

Deriving Hypotheses

Again, a hypothesis is a prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate. Theories and hypotheses always have this if-then relationship. “ If drive theory is correct, then cockroaches should run through a straight runway faster, and a branching runway more slowly, when other cockroaches are present.” Although hypotheses are usually expressed as statements, they can always be rephrased as questions. “Do cockroaches run through a straight runway faster when other cockroaches are present?” Thus deriving hypotheses from theories is an excellent way of generating interesting research questions.

But how do researchers derive hypotheses from theories? One way is to generate a research question using the techniques discussed in Chapter 2 “Getting Started in Research” and then ask whether any theory implies an answer to that question. For example, you might wonder whether expressive writing about positive experiences improves health as much as expressive writing about traumatic experiences. Although this is an interesting question on its own, you might then ask whether the habituation theory—the idea that expressive writing causes people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings—implies an answer. In this case, it seems clear that if the habituation theory is correct, then expressive writing about positive experiences should not be effective because it would not cause people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings. A second way to derive hypotheses from theories is to focus on some component of the theory that has not yet been directly observed. For example, a researcher could focus on the process of habituation—perhaps hypothesizing that people should show fewer signs of emotional distress with each new writing session.

Among the very best hypotheses are those that distinguish between competing theories. For example, Norbert Schwarz and his colleagues considered two theories of how people make judgments about themselves, such as how assertive they are (Schwarz et al., 1991). Both theories held that such judgments are based on relevant examples that people bring to mind. However, one theory was that people base their judgments on the number of examples they bring to mind and the other was that people base their judgments on how easily they bring those examples to mind. To test these theories, the researchers asked people to recall either six times when they were assertive (which is easy for most people) or 12 times (which is difficult for most people). Then they asked them to judge their own assertiveness. Note that the number-of-examples theory implies that people who recalled 12 examples should judge themselves to be more assertive because they recalled more examples, but the ease-of-examples theory implies that participants who recalled six examples should judge themselves as more assertive because recalling the examples was easier. Thus the two theories made opposite predictions so that only one of the predictions could be confirmed. The surprising result was that participants who recalled fewer examples judged themselves to be more assertive—providing particularly convincing evidence in favor of the ease-of-retrieval theory over the number-of-examples theory.

Evaluating and Revising Theories

If a hypothesis is confirmed in a systematic empirical study, then the theory has been strengthened. Not only did the theory make an accurate prediction, but there is now a new phenomenon that the theory accounts for. If a hypothesis is disconfirmed in a systematic empirical study, then the theory has been weakened. It made an inaccurate prediction, and there is now a new phenomenon that it does not account for.

Although this seems straightforward, there are some complications. First, confirming a hypothesis can strengthen a theory but it can never prove a theory. In fact, scientists tend to avoid the word “prove” when talking and writing about theories. One reason for this is that there may be other plausible theories that imply the same hypothesis, which means that confirming the hypothesis strengthens all those theories equally. A second reason is that it is always possible that another test of the hypothesis or a test of a new hypothesis derived from the theory will be disconfirmed. This is a version of the famous philosophical “problem of induction.” One cannot definitively prove a general principle (e.g., “All swans are white.”) just by observing confirming cases (e.g., white swans)—no matter how many. It is always possible that a disconfirming case (e.g., a black swan) will eventually come along. For these reasons, scientists tend to think of theories—even highly successful ones—as subject to revision based on new and unexpected observations.

A second complication has to do with what it means when a hypothesis is disconfirmed. According to the strictest version of the hypothetico-deductive method, disconfirming a hypothesis disproves the theory it was derived from. In formal logic, the premises “if A then B ” and “not B ” necessarily lead to the conclusion “not A .” If A is the theory and B is the hypothesis (“if A then B ”), then disconfirming the hypothesis (“not B ”) must mean that the theory is incorrect (“not A ”). In practice, however, scientists do not give up on their theories so easily. One reason is that one disconfirmed hypothesis could be a fluke or it could be the result of a faulty research design. Perhaps the researcher did not successfully manipulate the independent variable or measure the dependent variable. A disconfirmed hypothesis could also mean that some unstated but relatively minor assumption of the theory was not met. For example, if Zajonc had failed to find social facilitation in cockroaches, he could have concluded that drive theory is still correct but it applies only to animals with sufficiently complex nervous systems.

This does not mean that researchers are free to ignore disconfirmations of their theories. If they cannot improve their research designs or modify their theories to account for repeated disconfirmations, then they eventually abandon their theories and replace them with ones that are more successful.

Incorporating Theory Into Your Research

It should be clear from this chapter that theories are not just “icing on the cake” of scientific research; they are a basic ingredient. If you can understand and use them, you will be much more successful at reading and understanding the research literature, generating interesting research questions, and writing and conversing about research. Of course, your ability to understand and use theories will improve with practice. But there are several things that you can do to incorporate theory into your research right from the start.