- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

Dementia: A Very Short Introduction

Author webpage

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Dementia: A Very Short Introduction explains how dementia is diagnosed, its different types and symptoms, and its effects on sufferers and their families. Why is dementia resistant to treatment? Why has the most successful scientific hypothesis not led to a cure? Are there variations between different countries, and given the rise in the ageing population, are there more or fewer cases than we think? This VSI looks at the history of dementia research and examines the genetic, physiological, and environmental risk factors and how individuals might reduce them. It also investigates developments in diagnosis and symptom management, and the economic and political context of dementia care.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

External resource

- In the OUP print catalogue

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Advertisement

Machine Learning for Dementia Prediction: A Systematic Review and Future Research Directions

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 01 February 2023

- Volume 47 , article number 17 , ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Ashir Javeed 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Ana Luiza Dallora 2 na1 ,

- Johan Sanmartin Berglund 2 ,

- Arif Ali 3 ,

- Liaqata Ali 4 &

- Peter Anderberg 2 , 5

16k Accesses

26 Citations

46 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Nowadays, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have successfully provided automated solutions to numerous real-world problems. Healthcare is one of the most important research areas for ML researchers, with the aim of developing automated disease prediction systems. One of the disease detection problems that AI and ML researchers have focused on is dementia detection using ML methods. Numerous automated diagnostic systems based on ML techniques for early prediction of dementia have been proposed in the literature. Few systematic literature reviews (SLR) have been conducted for dementia prediction based on ML techniques in the past. However, these SLR focused on a single type of data modality for the detection of dementia. Hence, the purpose of this study is to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of ML-based automated diagnostic systems considering different types of data modalities such as images, clinical-features, and voice data. We collected the research articles from 2011 to 2022 using the keywords dementia, machine learning, feature selection, data modalities, and automated diagnostic systems. The selected articles were critically analyzed and discussed. It was observed that image data driven ML models yields promising results in terms of dementia prediction compared to other data modalities, i.e., clinical feature-based data and voice data. Furthermore, this SLR highlighted the limitations of the previously proposed automated methods for dementia and presented future directions to overcome these limitations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Diagnosis of Early Alzheimer’s Disease: Clinical Practice in 2021

Artificial intelligence in disease diagnosis: a systematic literature review, synthesizing framework and future research agenda

Alzheimer’s Disease: Epidemiology and Clinical Progression

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over a period of time, the advancements made in the field of medical science helped to increase the lifespan in the modern world [ 1 ]. This increased life expectancy raised the prevalence of neurocognitive disorders, affecting a significant part of the older population as well as global economies. In 2010, it was estimated that $604 billion have been spent on dementia patients in the USA alone[ 2 ]. The number of dementia patients is rapidly increasing worldwide, and statistical projections suggest that 135 million people might be affected by dementia by 2050 [ 3 ]. There are several risk factors that contribute to the development of dementia, including aging, head injury, and lifestyle. While age is the most prominent risk factor for dementia; figures suggest that a person at the age of 65 years old has 1–2% risk of developing dementia disease. By the age of 85 years old, this risk can reach to 30% [ 4 ].

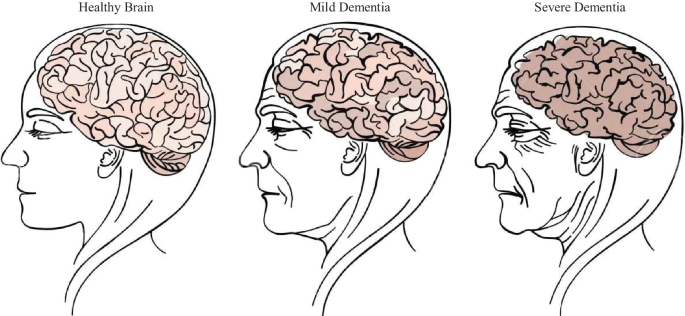

Dementia is a mental disorder that is characterized by a progressive deterioration of cognitive functions that can affect daily life activities such as memory, problem solving, visual perception, and the ability to focus on a particular task. Usually, older adults are most vulnerable to dementia, and people take it as an inevitable consequence of aging, which is perhaps the wrong perception. Dementia is not a part of the normal ageing process; however, it should be considered a serious form of cognitive decline that affects your daily life. Actually, the primary cause for the development of dementia is the several diseases and injuries that affect the human brain [ 5 ]. Dementia is ranked on the seventh place in the leading causes of deaths in the world [ 6 ]. Furthermore, it is the major cause of disability and dependency among older people globally [ 6 ]. A change in the person’s ordinary mental functioning and obvious signs of high cognitive deterioration are required for a diagnosis of dementia [ 7 ]. Figure 1 presents the progression of dementia with age.

Progression of dementia disease with ageing

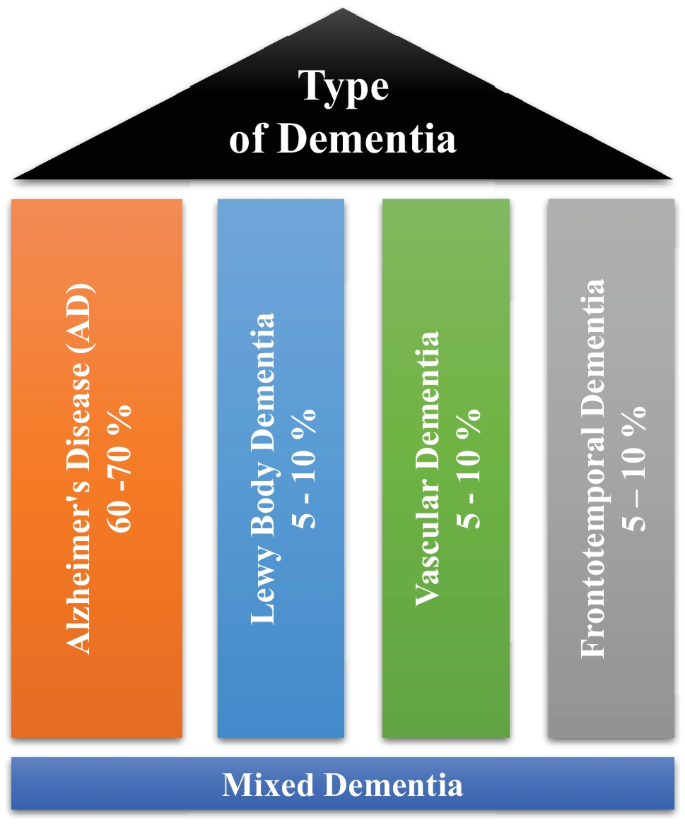

Types of dementia

Dementia is not a single disease, but, it is used as a generic term for several different cognitive disorders. Figure 2 provides the overview of different types of dementia along with the percentage of particular dementia type occurrence in the patients [ 8 ]. To have a better idea about dementia, we have studied common types of dementia for better problem awareness.

Types of dementia disease

Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is thought to develop when abnormal amounts of amyloid beta (A \(\beta\) ) build up in the brain, either extracellularly as amyloid plaques, tau proteins or intracellularly as neurofibrillary tangles, affecting neuronal function, connectivity and leading to progressive brain function loss [ 9 ]. This diminished ability to eliminate proteins with ageing is regulated by brain cholesterol [ 10 ] and is linked to other neurodegenerative illnesses [ 11 ]. Except for 1–2% of cases where deterministic genetic anomalies have been discovered, the aetiology of the majority of Alzheimer’s patients remains unexplained [ 12 ]. The amyloid beta (A \(\beta\) ) hypothesis and the cholinergic hypothesis are two competing theories presented to explain the underlying cause of AD [ 13 ].

Vascular dementia

Vascular dementia (VaD) is a subtype of dementia caused by problems with the brain’s blood flow, generally in the form of a series of minor strokes, which results in a slow decline of cognitive capacity [ 14 ]. The VaD refers to a disorder characterized by a complicated mix of cerebrovascular illnesses that result in structural changes in the brain, as a result of strokes and lesions, which lead to cognitive impairment. A chronological relationship between stroke and cognitive impairments is necessary to make the diagnosis [ 15 ]. Ischemic or hemorrhagic infarctions in several brain areas, such as the anterior cerebral artery region, the parietal lobes, or the cingulate gyrus, are associated with VaD. In rare cases, infarcts in the hippocampus or thalamus might cause dementia [ 16 ]. A stroke increases the risk of dementia by 70%, whereas a recent stroke increases the risk by almost 120% [ 17 ]. Brain vascular lesions can also be caused by diffuse cerebrovascular disease, such as small vessel disease [ 18 ]. Risk factors for VaD include age, hypertension, smoking, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and cerebrovascular sickness; geographic origin, genetic proclivity, and past strokes are also risk factors [ 19 ]. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy, which develops when beta amyloid accumulates in the brain, can occasionally lead to vascular dementia.

Lewy body dementia

Lewy body dementia (LBD) is a subtype of dementia characterized by abnormal deposits of the protein alpha-synuclein in the brain. These deposits, known as Lewy bodies, affect brain chemistry, causing problems with thinking, movement, behavior, and mood. Lewy body dementia is one of the most common causes of dementia [ 20 ]. Progressive loss of mental functions, visual hallucinations, as well as changes in alertness and concentration are prevalent in persons with LBD. Other adverse effects include tight muscles, delayed movement, difficulty walking, and tremors, all of which are also signs and symptoms of Parkinson’s disease [ 21 ]. LBD might be difficult to identify. Early LBD symptoms are commonly confused with those of other brain diseases or mental problems. Lewy body dementia can occur alone or in conjunction with other brain disorders [ 22 ]. It is a progressive disorder, which means that symptoms emerge gradually and worsen with time. A timespan of five to eight years is averaged, although it can last anywhere from two to twenty years for certain people [ 23 ]. The rate at which symptoms arise varies greatly from person to person, depending on overall health, age, and the severity of symptoms.

Frontotemporal dementia

Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) is a subtype of dementia characterized by nerve cell loss in the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain [ 24 ]. As a result, the lobes contract. FTD can have an impact on behavior, attitude, language, and movement. This is one of the most common dementias in people under the age of 65. FTD most commonly affects persons between the ages of 40 and 65; however, it may also afflict young adults and older individuals [ 25 ]. The lobes decrease, and behavior, attitude, language, and mobility can all be affected by FTD. FTD affects both men and women equally. Dissociation from family, extreme oniomania, obscene speech, screaming, and the inability to regulate emotions, behavior, personality, and temperament are examples of social display patterns caused by FTD [ 26 ]. The symptoms of FTD appeared several years prior to visiting a neurologist [ 27 ].

Mixed Dementia (MD)

Mixed dementia occurs, when more than one kind of dementia coexists in a patient, and it is estimated to happen in around 10% of all dementia cases [ 6 ]. AD and VaD dementia are the two subtypes that are most common in MD [ 28 ]. This case is usually associated with factors such as old age, high blood pressure, and brain blood vessel damage [ 29 ]. Because one dementia subtype often predominates, MD is difficult to identify. As a result, the individuals affected by MD are rarely treated and miss out on potentially life-changing medicines. MD can cause symptoms to begin earlier than the actual diagnosis of the disease and spread swiftly to affect the most areas of the brain [ 30 ].

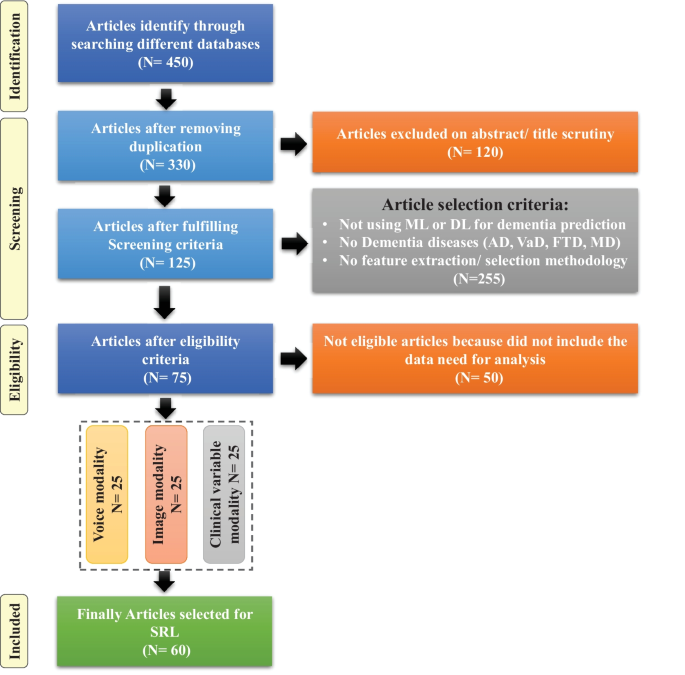

Recently, numerous automated methods have been developed based on machine learning for early the prediction of different diseases [ 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 ]. This systematic literature review (SLR) presented hereby, investigates machine learning-based automated diagnostic systems that are designed and developed by scientists to predict dementia and its subtypes, such as AD, VaD, LBD, FTD and MD. We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) criteria to conduct this SLR [ 49 , 50 ]. A comprehensive search was conducted to retrieve the research articles that contain ML approaches to predict the development of dementia and its subtypes using three different types of data modalities (images, clinical-variables, voice).

Aim of the study

SLRs are done to synthesize current evidence, to identify gaps in the literature, and to provide the groundwork for future studies [ 51 ]. Previous, SLRs studies have been done on automated diagnostic systems for dementia prediction based on ML approaches, which focused on a single sort of data modality. These SLR investigations did not emphasize the limits of previously published automated approaches for dementia prediction. The SLR presented herein assesses the previously proposed automated diagnostic systems based on deep learning (DL) and ML algorithms for the prediction of dementia and its common subtypes (e.g. AD, VaD, FTD, MD). The aim of this SLR is to analyse and evaluate the performance of automated diagnostic systems for dementia prediction using different data modalities. The main question is decomposed in the following sub-research questions:

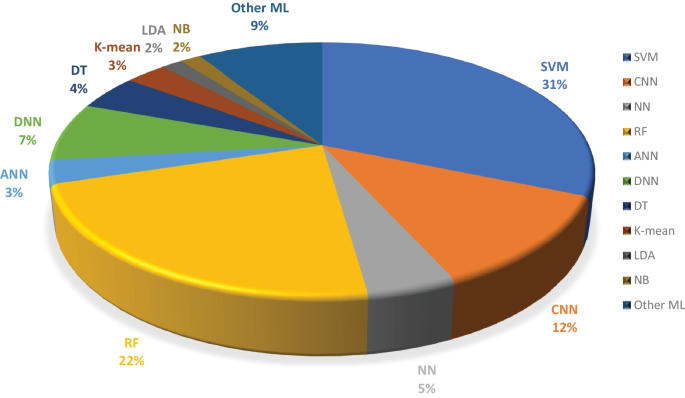

What types of ML and DL techniques have been used by researchers to diagnose dementia?

Examine the methods of feature extraction or selection used by the researchers.

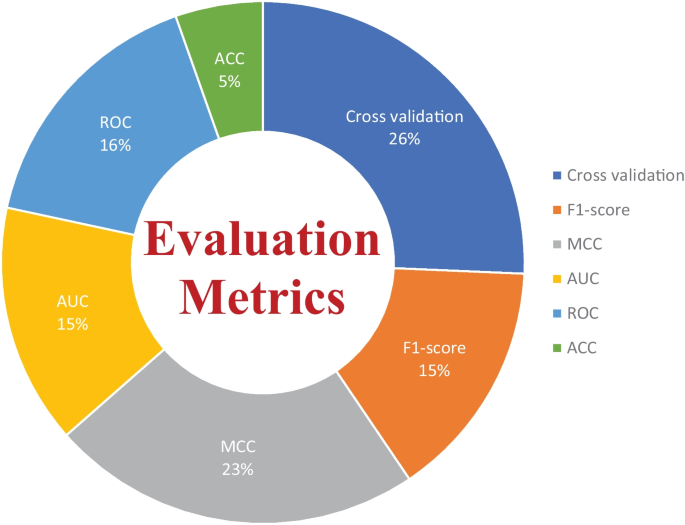

Analyze the different performance evaluation measures that are adopted by the researcher to validate the effectiveness of the proposed diagnostic system for demetnia.

Analyze the performance of ML models on various data types.

Identification of weaknesses in previously proposed ML models for dementia prediction.

Flow diagram of PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses)

Article selection

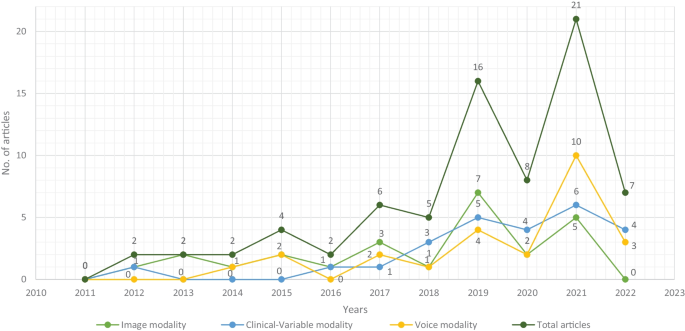

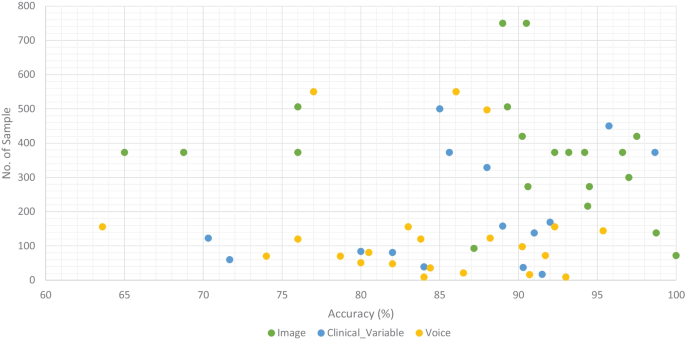

For this SLR study, the research articles were selected based on keywords such as ML, DL, dementia and its subtypes (AD, VaD, FTD, and MD). For the collection of research articles, we conducted an electronic search from different online databases such as ScienceDirect, PubMed, IEEE Xplore Digital Library, Springer, Hindawi, and PLOs, which helped to gather 450 research studies on the specific topic. After reviewing the title and abstract in each study, 120 publications were found to be ineligible for processing, while 330 articles were selected for further processing. Following the deduplication of data, 125 full-text publications were retrieved for further processing after the screening phase of the article selection, with 205 of them being eliminated due to not satisfying the article selection criteria of the screening phase. Finally, 50 research articles were eliminated due to not fulfilling the eligibility criteria for article selection. The final set of selected papers consisted of 75 research papers, among these final selected articles, each of the data modalities (image, clinical-variables, voice) contained 25 papers. After rerunning the database searches in May 2022, no further suitable research article was found for the selection. Figure 3 presents the workflow for article selection, which includes the four PRISMA guidelines-recommended steps such as identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion [ 49 , 50 ]. In recent years, ML scientists have shown a strong interest in designing and developing ML-based automated diagnostic systems for dementia prediction. Therefore, the number of research articles in this research area has been increased and it can be depicted from Fig. 4 where research articles are published years wise with regarding data modality. The publications utilized in this study were selected based on the following criteria:

Studies that present automated diagnostic systems for dementia and its common subtypes (AD,VaD, FTD, MD).

Studies published between 2011 and 2022.

Studies employing ML approaches for dementia diagnosis.

Studies which have utilized several data modalities.

Studies published in the English language.

Selected research articles which are published from 2011 to 2022 regarding data modality

Machine learning for dementia

Over the years, the increasing use and availability of medical equipment has resulted in a massive collection of electronic health records (EHR) that might be utilized to identify dementia using developing technologies such as ML and DL [ 52 ]. These EHRs are one of the most widely available and used clinical datasets. They are a crucial component of contemporary healthcare delivery, providing rapid access to accurate, up-to-date, comprehensive patient information while also assisting with precise diagnosis and coordinated, efficient care [ 53 ]. Laboratory tests, vital signs, drugs, and other therapies, as well as comorbidities, can be used to identify the people at risk of dementia using the EHRs’ data [ 54 ]. In some situations, patients may also be subjected to costly and invasive treatments such as neuroimaging scans i.e., magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and position emission tomography (PET)) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) collection for biomarker testing [ 55 , 56 , 57 ]. These tests’ findings may also be found in the EHR. According to researchers, such longitudinal clinical EHR data can be used to track the advancement of AD dementia over time [ 58 ]. Recently, several automated diagnostic systems for different diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease [ 59 ], hepatitis [ 47 ], carcinoma [ 41 ], and heart failure [ 60 , 61 , 62 ] prediction have been designed by employing ML and DL techniques. Inspired by this fact, the unmet demand for dementia knowledge, along with the availability of relevant huge datasets, has motivated scientists to investigate the utility of artificial intelligence (AI), which is gaining a prominent role in the area of healthcare innovation [ 63 ]. ML, a subset of AI, can model the relationship between input quantities and clinical outcomes, identify hidden patterns in enormous volumes of data, and draw conclusions or make decisions that help with more accurate clinical decision-making [ 51 ]. However, computational hypotheses generated by ML models must still be confirmed by subject matter experts in order to achieve enough precision for clinical decision-making [ 64 ].

In this SLR, we have included studies that have used ML predictive models (supervised and unsupervised) for dementia prediction and excluded studies that have used statistical methods for cohort summarization and hypothesis testing (e.g., odds ratio, chi-square distribution, Kruskal-Wallis test, and Kappa-Cohen test). Furthermore, we have referenced the data modality-based study [ 65 ] for this literature review, where we have categorized the three data modality types such as image, clinical-variable and voice. Thus, we have studied each modality-based automated diagnostic system for dementia prediction that has been proposed in the past using ML and DL.

This section explains the datasets that were used in the selected research papers for experiments and performance evaluation of the proposed automated diagnostic systems designed by the researchers using ML algorithms for dementia and its subtypes. A total of 61 datasets were studied from the selected research articles. These datasets are compiled from a wide range of organizations and hospitals throughout the world. Only a few datasets are openly available to the public, while others are compiled by researchers from various hospitals and healthcare institutes. We have only included datasets that have been used to diagnose AD, VaD, FTD, MD, and LBD using ML and DL techniques. On the basis of data modality, we have categorised the dataset into three types: images, clinical_variables and voice datasets. The datasets differ in terms of the number of variables (features) and samples. As a result, we examined each modality of the dataset one by one.

Image modality based datasets

There are several image datasets based on brain imaging, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), collected by the researchers for the diagnosis of dementia. From the Table 1 , it can be depicted that Open Access Series of Imaging Studies (OASIS) and Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) datasets are mostly used by the researchers for the experimental purpose. OASIS aims to make neuroimaging datasets available to the scientific community for free. By gathering and openly disseminating this multimodal dataset produced by the Knight ADRC and its related researchers, they had used different samples and variables of the datasets in their research work. ADNI researchers acquire, validate, and use data such as MRI, PET imaging, genetics, cognitive assessments, CSF, and blood biomarkers as disease predictors. The ADNI website contains research information and data from the North American ADNI project, which includes Alzheimer’s disease patients, people with mild cognitive impairment, and older controls. Table 1 provides us with the following information: dataset_id, dataset name, number of samples in the particular dataset, variables in the dataset, and finally, the type of dementia.

Clinical-variables modality based datasets

Throughout the course of time, the growing usage and availability of medical devices have resulted in an overwhelming collection of clinical EHR data. Furthermore, the patient’s medical history consists of medical tests and clinical records that can be used for the prediction of diseases. Thus, the importance of clinical data emerges as a vital tool for proactive management of disease. The dataset based on clinical variables for dementia consists of medical tests that are used by doctors to check the dementia status in patients, such as the Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE), the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS), and the Brief Interview for Mental Status (BIMS). Clinical-variables based datasets consist of information about these medical tests along with patient personal information, i.e., age, sex, and marital status. Hereby, Table 2 provides the information regarding clinical-variables modality-based datasets that are used by the researchers for the design and development of automated diagnostic systems for dementia patients based on ML. Table 2 presents the dataset_id, dataset name, number of samples in the particular dataset, variables in the dataset, and finally the type of dementia.

Voice modality based datasets

Speech analysis is a useful technique for clinical linguists in detecting various types of neurodegenerative disorders affecting the language processing areas. Individuals suffering from Parkinson’s disease (PD, deterioration of voice quality, unstable pitch), Alzheimer’s disease (AD, monotonous pitch), and the non-fluent form of Primary Progressive Aphasia (PPA-NF, hesitant, non-fluent speech) may experience difficulties with prosody, fluency, and voice quality. Besides imaging and clinical-variables data, the researchers employed voice recording data to identify dementia using ML and DL algorithms. The data collection process for voice data varies from dataset to dataset, for example, in a few datasets, patients were requested to answer a prepared set of questions (interview) in a specific time interval. In a few datasets, selected neuropsychological tests were carried out, the description of each neuropsychological test was played and was followed by an answering window. Table 3 presents the dataset_id, dataset name, number of samples in the particular dataset, variables in the dataset, and finally the subtype of dementia.

Data sharing challenges

In this digital era, public health decision-making has grown progressively complicated, and the utilization of data has become critical [ 66 ]. Data are employed at the local level to observe public health and target interventions; at the national scale for resource allocation, prioritization, and planning; and at the global scale for disease burden estimates, progress in health and development measurement, and the containment of evolving global health threats [ 67 , 68 ]. Van Panhuis et al. have adequately described the challenges to exchanging health data [ 69 ]. Based on our initial analysis, we built on this taxonomy to identify the hurdles related to data sharing in global public health, and we have highlighted how they may apply to each typology as given below.

Lack of complete data, lost data, restrictive as well as conflicting data formats, a lack of metadata and standards, a lack of interoperability of datasets (e.g., structure or “language”), and a lack of appropriate analytic solutions are examples of technical barriers encountered by health information management systems.

Individuals and organizations face motivational challenges when it comes to sharing data. These impediments include a lack of incentives, opportunity costs, apprehension about criticism, and disagreements over data usage and access.

The potential and present costs of sharing data are both economic hurdles.

Political obstacles are those that are built into the norms of local health governance and often emerge as regulations and guidelines. They can also entail trust and ownership difficulties.

Legal issues that arise as a result of data collection, analysis, and usage include questions regarding who owns or controls the data, transparency, informed permission, security, privacy, copyright, human rights, damage, and stigma.

Ethical constraints include a lack of perceived reciprocity (i.e., the other side will not disclose data) and proportionality (i.e., deciding not to share data based on an assessment of the risks and benefits). An overall concern is that frameworks, rules, and regulations have not kept up with technological changes that are transforming how data is collected, analyzed, shared, and used.

ML based diagnostic models for dementia: Image modality

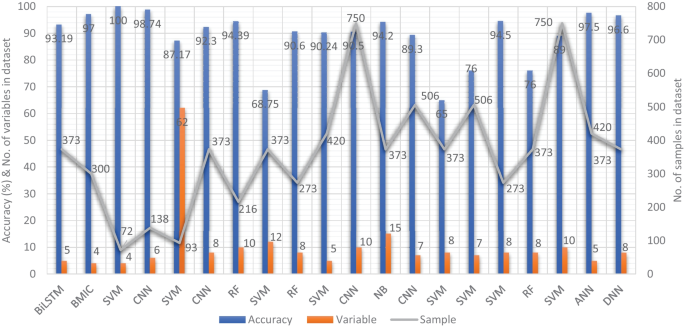

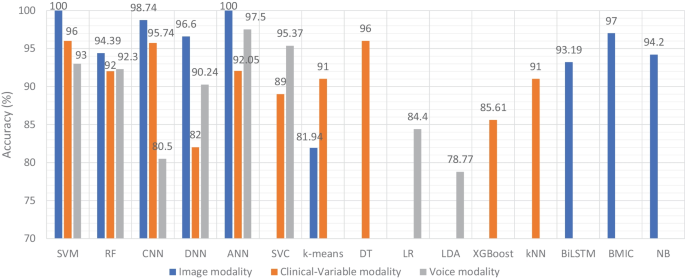

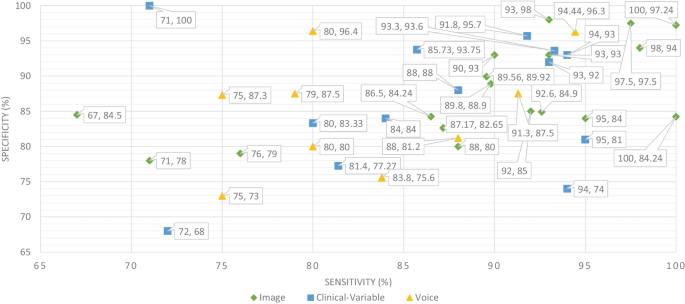

In recent years, researchers have designed many ML and DL algorithms for the detection of dementia and its subtypes using MRI images of the brain. For example, Dashtipour et al. [ 70 ] proposed a ML based method for the prediction of Alzheimer’s disease. In their proposed model, they used DL techniques to extract the features from brain images, and for classification purposes, they deployed SVM and bidirectional long short-term memory (BiLSTM). Through their proposed model, they had reported the classification accuracy of 91.28%. Moreover, for early detection of the AD, a DL based approach was proposed by Helaly et al. In their proposed work, they employed convolutional neural networks (CNN). The Alzheimer’s disease spectrum is divided into four phases. Furthermore, different binary medical image classifications were used for each two-pair class of Alzheimer’s disease stages. Two approaches were used to categorize medical images and diagnose Alzheimer’s disease. The first technique employs basic CNN architectures based on 2D and 3D convolution to cope with 2D and 3D structural brain images from the ADNI dataset. They had achieved highly promising accuracies for 2D and 3D multi-class AD stage classification of 93.61% and 95.17%, respectively. The VGG19 pre-trained model had been fine-tuned and obtained an accuracy of 97% for multi-class AD stage classification [ 71 ]. Vandenberghe et al. had proposed a method for binary classification of 18F-flutemetramol PET using ML techniques for AD and mild cognitive impairment (MCI). They had tested whether support vector machines (SVM), a supervised ML technique, can duplicate the assignments made by blindfolded visual readers, as well as which image components had the highest diagnostic value according to SVM and how 18F-fluoromethylamol-based SVM classification compares to structural MRI-based SVM classification in the same cases. Their F-flutemetamol based classifier was able to replicate the assignments obtained by visual read with 100% accuracy [ 72 ]. Odusami et al. proposed a novel method for the detection of early-stage dementia from functional brain changes in MRI using a fine-tuned ResNet-18 network. Their research work presents a DL based technique for predicting MCI, early MCI, late MCI, and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The ADNI fMRI dataset was used for analysis and consisted of 138 participants. On EMCI vs. AD, LMCI vs. AD, and MCI vs. AD, the fine-tuned ResNet18 network obtained classification accuracy of 99.99%, 99.95%, and 99.95%, respectively [ 73 ]. Zheng et al. had presented a ML based framework for differential diagnosis between VaD and AD using structural MRI features. The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) was then used to build a feature set that was fed into SVM for classification. To ensure unbiased evaluation of model performance, a comparative analysis of classification models was conducted using different ML algorithms to discover which one had better performance in the differential diagnosis between VaD and AD. The diagnostic performance of the classification models was evaluated using quantitative parameters derived from the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC). The experimental finding had shown that the SVM with RBF performed well for the differential diagnosis of VaD and AD, with sensitivity (SEN), specificity (SPE), and accuracy (ACC) values of 82.65%, 87.17%, and 84.35%, respectively (AUC = 86.10–95%, CI = 0.820–0.902) [ 74 ]. Basheer et al. [ 75 ] had presented an innovative technique by making improvements in capsule network design for the best prediction outcomes. The study used the OASIS dataset with dimensions (373 X 15) to categorize the labels as demented or non-demented. To make the model swifter and more accurate, several optimization functions were performed on the variables, as well as the feature selection procedure. The claims were confirmed by demonstrating the correlation accuracy at various iterations and layers with an allowable accuracy of 92.39%. L. K. Leong and A. A. Abdullah had proposed a method for the prediction of AD based on ML techniques with the Boruta algorithm as a feature selection method. According to the Boruta algorithm, Random Forest Grid Search Cross Validation (RF GSCV) outperformed other 12 ML models, including conventional and fine-tuned models, with 94.39% accuracy, 88.24% sensitivity, 100.00% specificity, and 94.44% AUC even for the small OASIS-2 longitudinal MRI dataset [ 76 ]. Battineni et al. had presented a SVM based ML model for the prediction of dementia. Their proposed model had achieved an accuracy and precision of 68.75% and 64.18% using the OASIS-2 dataset [ 77 ]. Mathotaarachchi et al. had analyzed the amyloid imaging using ML approaches for the detection of dementia. To overcome the inherent unfavorable and imbalance proportions between persons with stable and progressing moderate cognitive impairment in a short observation period. The innovative method had achieved 84.00% accuracy and an AUC of 91.00% for the ROC [ 78 ]. Aruna and Chitra had presented a ML approach for the identification of dementia from MRI images, where they had deployed Independent Component Analysis (ICA) to extract the features from the images, and for classification purposes, SVM with different kernels is used. Through their proposed method, they had obtained an accuracy of 90.24% [ 79 ] (Fig. 5 ).

Accuracy comparison of different ML models based on image modality

Supervised ML techniques and CNNs were examined by Herzog and Magoulas. They had achieved the accuracy of 92.5% and 75.0% for NC vs EMCI, 93.0% and 90.5% for NC vs. AD, respectively [ 80 ]. Battineni et al. had comprehensive applied ML model on MRI to predict Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in older subjects, and they had proposed two ML models for AD detection. In the first trial, manual feature selection was utilized for model training, and ANN produced the highest AUC of 81.20% by ROC. The NB had earned the greatest AUC of 94.20% by ROC in the second trial, which included wrapping approaches for the automated feature selection procedure [ 81 ]. Ma et al. had conducted a study where they compared feature-engineered and non-feature-engineered ML methods for blinded clinical evaluation for dementia of Alzheimer’s type classification using FDG-PET. The highest accuracy of 84.20% was obtained through CNN’s [ 82 ]. Bidani et al. had presented a novel approach in the field of DL that combines both the deep convolutional neural network (DCNN) model and the transfer learning model to detect and classify dementia. When the features were retrieved, the dementia detection and classification strategy from brain MRI images using the DCNN model provided an improved classification accuracy of 81.94%. The transfer learning model, on the other hand, had achieved an accuracy of 68.13% [ 83 ].

Moscoso et al. had designed a predictive model for the prediction of Alzheimer’s disease using MRI images. Their proposed model had obtained the highest accuracy of 84.00% [ 84 ]. Khan and Zubair had presented an improved multi-modal based ML approach for the prognosis of AD. Their proposed model had a five-stage ML pipeline, where each stage was further categorized into different sub-levels. Their proposed model had reported the highest accuracy of 86.84% using RF [ 85 ]. Mohammed et al. had evaluated the two CNN models (AlexNet and ResNet-50) and hybrid DL/ML approaches (AlexNet+SVM and ResNet-50+SVM) for AD diagnosis using the OASIS dataset. They had found that RF algorithm had attained an overall accuracy of 94%, as well as precision, recall, and F1 scores of 93%, 98%, and 96%, respectively [ 86 ]. Salvatore et al. had developed a ML method for early AD diagnosis using magnetic resonance imaging indicators. In their proposed ML model, they used PCA for extracting features from the images and SVM for the classification of dementia. They had achieved a classification accuracy of 76% using a 20-fold cross validation scheme [ 87 ]. Katako et al. had identified the AD related FDGPET pattern that is also found in LBD and Parkinson’s disease dementia using ML approaches. They studied different ML algorithms, but SVM with an iterative single data algorithm produced the best performance, i.e., sensitivity 84.00%, specificity 95.00% through 10-fold cross-validation [ 88 ]. Gray et al. had presented a system in which RF proximities were utilized to learn a low-dimensional manifold from labelled training data and then infer the clinical labels of test data that translated to this space. Their proposed model, voxel-based (FDG-PET), obtained an accuracy of 87.9% using ten-fold cross-validation [ 89 ]. Table 4 provides the overall performance evaluation of the ML models that were presented by the researchers for the prediction of dementia and its subtypes by using image data as a modality.

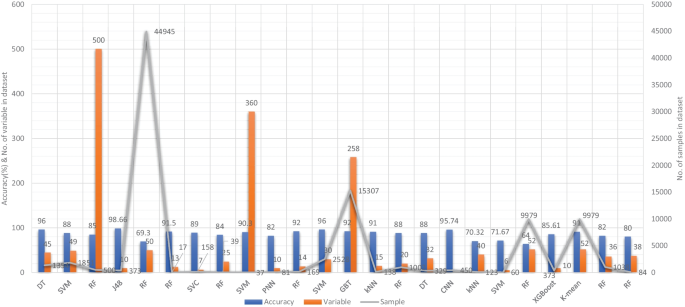

ML based diagnostic models for dementia: Clinical-variable modality

Aside from image-based ML techniques for dementia prediction, several research studies have utilized clinical-variable data with ML algorithms to predict dementia and its subtypes. For instance, Chiu et al. had designed a screening instrument to detect MCI and dementia using ML techniques. They had developed a questionnaire to assist neurologists and neuropsychologists in the screening of MCI and dementia. The contribution of 45 items that matched the patient’s replies to questions was ranked using feature selection through information gain (IG). Among the 45 items, 12 were ranked the highest in feature selection. The ROC analysis showed that AUC in test group was 94.00% [ 96 ]. Stamate et al. had developed a framework for the prediction of MCI and dementia. Their proposed framework was based on the ReliefF approach paired with statistical permutation tests for feature selection, model training, tweaking, and testing using ML algorithms such as RF, SVM, Gaussian Processes, Stochastic Gradient Boosting, and eXtreme Gradient Boosting. The stability of model performances was studied using computationally expensive Monte Carlo simulations, and the results of their proposed framework were given as for dementia detection, the accuracy was 88.00%, sensitivity was 93.00%, and the specificity was 94.00%, whereas moderate cognitive impairment had a sensitivity of 86.00% and a specificity of 90% [ 97 ]. Stamate et al. developed a system for detecting dementia subtypes (AD) in blood utilizing DL and other supervised ML approaches such as RF and extreme gradient boosting. The AUC for the proposed DL method was 85% (0.80–0.89), for XGBoost it was 88% (0.86–0.89), and for RF it was 85% (0.83–0.87). In comparison, CSF measurements of amyloid, p-tau, and t-tau (together with age and gender) gave AUC values of 78%, 83%, and 87%, respectively, by using the XGBoost [ 98 ]. Bansal1 et al. had performed the comparative analysis of the different ML methods for the detection of dementia using clinical-variables. In their experiments, they exploited the performance of four ML models, such as J48, NB, RF, and multilayer perceptrons. From the results of experiments, they had concluded that j48 outperformed the rest of the ML models for the detection of dementia [ 99 ]. Nori et al. had experimented the lasso algorithm on a big dataset of patient and identify the 50 variables by ML model with an AUC of 69.30% [ 100 ]. Alam et al. [ 101 ]used signal processing on wearable sensor data streams (e.g., electrodermal activity (EDA), photoplethysmogram (PPG), and accelerometer (ACC)) and machine learning techniques to measure cognitive deficits and their relationship with functional health deterioration.

Gurevich et al. had used SVM and neuropsychological test for the classification of AD from other causes of cognitive impairment. The highest classification accuracy they had achieved through their proposed method was 89.00% [ 102 ]. Karaglani et al. had proposed a ML based automated diagnosis system for AD by using blood-based biosignatures. In their proposed method, they used mRNA-based statistically equivalent signatures for feature ranking and a RF model for classification. Their proposed automated diagnosis system had reported the accuracy of 84.60% using RF [ 103 ]. Ryzhikova et al. had analyzed cerebrospinal fluid for the diagnosis of AD by using ML algorithms. For classification purposes, artificial neural networks (ANN) and SVM discriminant analysis (SVM-DA) statistical methods were applied, with the best findings allowing for the distinguishing of AD and HC participants with 84.00% sensitivity and specificity. The proposed classification models have a high discriminative power, implying that the technique has a lot of potential for AD diagnosis [ 104 ]. Cho and Chen had designed a double layer dementia diagnosis system based on ML where fuzzy cognitive maps (FCMs) and probability neural networks (PNNs) were used to provide initial diagnoses at the base layer, and Bayesian networks (BNs) were used to provide final diagnoses at the top layer. Diagnosis results, “proposed treatment,” and “no treatment required” might be used to provide medical institutions with self-testing or secondary dementia diagnosis. The highest accuracy reported by their proposed system was 83.00% [ 105 ]. Facal et al. had studied the role of cognitive reserve in the conversion from MCI to dementia using ML. Nine ML classification algorithms were tried in their study, and seven relevant performance parameters were generated to assess the prediction accuracy for converted and non-converted individuals. The use of ML algorithms on socio-demographic, basic health, and CR proxy data allowed for the prediction of dementia conversion. The Gradient Boosting Classifier (ACC = 0.93; F1 = 0.86 and Cohen’s kappa = 0.82) and RF Classifier (ACC = 92%; F1 = 0.79 and Cohen’s kappa = 0.71) performed the best [ 106 ]. Jin et al. had proposed automatic classification of dementia from learning of clinical consensus diagnosis in India using ML techniques. All viable ML models exhibited remarkable discriminative skills (AUC >90%) as well as comparable accuracy and specificity (both around 95%). The SVM model beat other ML models by obtaining the highest sensitivity (0.81), F1 score (0.72), kappa (.70, showing strong agreement), and accuracy (second highest) (0.65). As a consequence, the SVM was chosen as the best model in their research work [ 107 ]. James et al. had evaluated the performance of ML algorithms for predicting the progression of dementia in memory clinic patients. According to their findings, ML algorithms outperformed humans in predicting incident all-cause dementia within two years. Using all 258 variables, the gradient-boosted trees approach had an overall accuracy of 92% , sensitivity of 0.45, specificity of 0.97, and an AUC of 0.92. Analysis of variable significance had indicated that just 6 variables were necessary for ML algorithms to attain an accuracy of 91% and an AUC of at least 89.00% [ 108 ]. Bougea et al. had investigated the effectiveness of logistic regression (LR), K-nearest neighbours (K-NNs), SVM, the Naive Bayes classifier, and the Ensemble Model to correctly predict PDD or DLB. The K-NN classification model exhibited an overall accuracy of 91.2% based on 15 top clinical and cognitive scores, with 96.42% sensitivity and 81% specificity in distinguishing between DLB and PDD. Based on the 15 best characteristics, the binomial logistic regression classification model had attained an accuracy of 87.5%, with 93.93% sensitivity and 87% specificity. Based on the 15 best characteristics, the SVM classification model had achieved an accuracy of 84.6% of overall instances, 90.62% sensitivity, and 78.58% specificity. A model based on NB classification obtained an accuracy of 82.05%, sensitivity of 93.10%, and a specificity of 74.41%. Finally, an ensemble model, which was constructed by combining the separate ones, attained 89.74% accuracy, 93.75% sensitivity, and 85.73% specificity [ 109 ] (Fig. 6 ).

Accuracy comparison of different ML models based on clinical-variable modality

Salem et al. had presented a regression-based ML model for the prediction of dementia. In their proposed method, they had investigated ML approaches for unbalanced learning. In their suggested supervised ML approach, they started by intentionally oversampling the minority class and undersampling the majority class, in order to reduce the bias of the ML model to be trained on the dataset. Furthermore, they had deployed cost-sensitive strategies to penalize the ML models when an instance was misclassified in the minority class. According to their findings, the balanced RF was the most resilient probabilistic model (with just 20 features/variables) with an F1 score of 0.82, a G-Mean of 0.88, and an AUC of 0.88 using ROC. With a F1-score of 0.74 and an AUC of 0.80 by ROC, the calibrated-weighted SVM was their top classification model for the same number of features [ 110 ]. Gutierrez et al. had designed an automated diagnosis system for the detection of AD and FTD by using feature engineering and genetic algorithms. Their proposed system had obtained the accuracy of 84% [ 111 ]. Mirzaei and Adeli had analyzed the state-of-the-art ML techniques used for the detection and classification of AD [ 112 ]. Hsiu et al. had studied ML algorithms for early identification of cognitive impairment. Their proposed model had obtained the accuracy of 70.32% by threefold cross-validation scheme [ 113 ]. Several classification models were constructed using various ML and feature selection methodologies to automate MCI detection using gait biomarkers. They had demonstrated, however, that dual-task walking differentiated between MCI and CN individuals. The ML model used for MCI pre-screening based on inertial sensor-derived gait biomarkers achieved 71.67% accuracy and 83.33% sensitivity, respectively, as reported by Shahzad et al. [ 114 ]. Hane et al. investigated the use of deidentified clinical notes acquired from multiple hospital systems over a 10-year period to enhance retrospective ML models predicting the risk of developing AD. The AUC improved from 85.00% to 94.00% by utilizing clinical notes, and the positive predictive value (PPV) rose from 45.07% (25,245/56,018) to 68.32% (14,153/20,717) in the model at the beginning of disease [ 115 ]. Table 5 provides the overall performance evaluation of the ML models that were presented by the researchers for the prediction of dementia and its subtypes by using clinical-variable data as a modality.

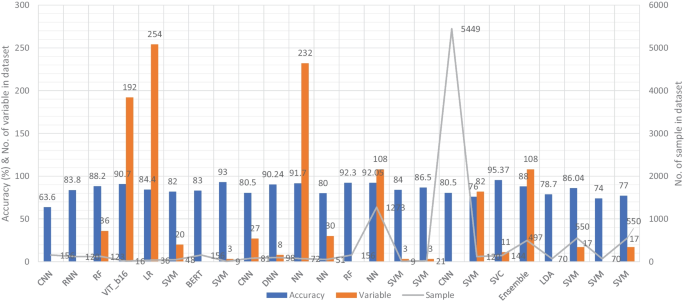

ML based diagnostic models for dementia: Voice modality

Similar to the image and clinical-variable modalities, researchers had also developed automated diagnostic systems based on voice data for the prediction of dementia. Hereby, we have reviewed the research work done by the scientists in detail. For example, Chlasta and Wolk had worked on the computer-based automated screening of dementia patients by spontaneous speech analysis using DL and ML techniques. In their work, they used neural networks to extract the features from the voice data; the extracted features were then fed into a linear SVM for classification purposes. Their SVM model had obtained the accuracy of 59.1% while CNN based ML model had reported the accuracy of 63.6% [ 121 ]. Chien et al. had presented an ML model for the assessment of AD using speech data. Their suggested model included a feature sequence that was used to extract the features from the raw audio data, as well as a recurrent neural network (RNN) for classification. Their proposed ML model had reported an accuracy of 83.80% based on the ROC curve [ 122 ]. Shimoda et al. had designed an ML model that identified the risk of dementia based on the voice feature in telephone conversations. Extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), RF, and LR based ML models were used, with each audio file serving as one observation. The predictive performance of the constructed ML models was tested by characterizing the ROC curve and determining the AUC, sensitivity, and specificity [ 123 ]. Nishikawa et al. had developed an ensemble discriminating system based on a classifier with statistical acoustic characteristics and a neural network of transformer models, with an F1-score of 90.70% [ 124 ]. Liu et al. had introduced a new technique for recognizing Alzheimer’s disease that used spectrogram features derived from speech data, which aided families in comprehending the illness development of patients at an earlier stage, allowing them to take preventive measures. They used ML techniques to diagnose AD using speech data collected from older adults who displayed the attributes described in the speech. Their proposed method had obtained the maximum accuracy of 84.40% based on LogisticRegressionCV [ 125 ]. Searle et al. had created a ML model to assess spontaneous speech, which might potentially give an efficient diagnostic tool for earlier AD detection. Their suggested model was a fundamental Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) vectorizer as input into an SVM model, and the top performing models were a pre-trained transformer-based model ’DistilBERT’ when used as an embedding layer into simple linear models. The proposed model had obtained the highest accuracy of 82.00% [ 126 ]. Zhu et al. had suggested an ML model that employed the speech pause as an effective biomarker in dementia detection, with the purpose of reducing the detection, model’s confidence levels by adding perturbation to the speech pauses of the testing samples. They next investigated the impact of the perturbation in training data on the detection model using an adversarial training technique. The proposed model had achieved an accuracy of 84.00% [ 127 ]. Ossewaarde et al. had proposed ML model based on SVM for the classification of spontaneous speech of individuals with dementia based on automatic prosody analysis. Their findings suggest that the classifier can distinguish some dementia types (PPA-NF, AD), but not others (PD) [ 128 ]. Xue et al. had developed an ML model based on DL for the detection of dementia by using voice recordings. In their ML model, long short-term memory (LSTM) network and the convolutional neural network (CNN) utilized audio recordings to categorize whether the recording contained a participant with either NC or only DE and to discriminate between recordings belonging to those with DE and those without DE (i.e., NDE (NC+MCI)) [ 129 ]. Weiner et al. had presented two pipelines of feature extraction for dementia detection: the manual pipeline used manual transcriptions, while the fully automatic pipeline used transcriptions created by automatic speech recognition (ASR). The acoustic and linguistic features that they had extracted need no language specific tools other than the ASR system. Using these two different feature extraction pipelines, they had automatically detect dementia [ 130 ] (Fig. 7 ).

Accuracy comparison of different ML models based on voice modality

Furthermore, Sadeghian et al. had presented the empirical evidence that a combination of acoustic features from speech, linguistic features were extracted from an automatically determined transcription of the speech including punctuation, and results of a mini mental state exam (MMSE) had achieved strong discrimination between subjects with a probable AD versus matched normal controls [ 131 ]. Khodabakhsh et al. had evaluated the linguistic and prosodic characteristics in Turkish conversational language for the identification of AD. Their research suggested that prosodic characteristics outperformed linguistic features by a wide margin. Three of the prosodic features had helped to achieve a classification accuracy of more than 80%, However, their feature fusion experiments did not improve classification performance any more [ 132 ]. Edwards et al. had analyzed the text data at both the word level and phoneme level, which leads to the best-performing system in combination with audio features. Thus, the proposed system was both multi-modal (audio and text) and multi-scale (word and phoneme levels). Experiments with larger neural language models had not resulted in improvement, given the small amount of text data available [ 133 ]. Kumar et al. had identified speech features relevant in predicting AD based on ML. They had deployed neural network for the classification and obtained the accuracy of 92.05% [ 134 ]. Ossewaarde et al. had built ML model based on SVM for the classification from spontaneous speech of individuals with dementia by using automatic prosody [ 128 ]. Luz et al. had developed an ML approach for analyzing patient speech in dialogue for dementia identification. They had designed a prediction model, and the suggested strategy leveraged additive logistic regression (ML boosting method) on content-free data gathered through dialogical interaction. Their proposed model obtained the accuracy of 86.50% [ 135 ]. Sysed et al. had designed a multimodal system that identified linguistic and paralinguistic traits of dementia using an automated screening tool. Their proposed system had used bag-of-deep-feature for feature selection and ensemble model for classification [ 136 ]. Moreover, Sarawgi et al. had used multimodal inductive transfer learning for AD detection and severity. Their proposed system further achieved state-of-the-art AD classification accuracy of 88.0% when evaluated on the full benchmark DementiaBank Pitt database. Table 6 provides the overall performance evaluation of the ML models that were presented by the researchers for the prediction of dementia and its subtypes by using voice-modality data.