Thetis Transporting Arms for Achilles (detail) by William Theed the Elder (ca. 1804–1812)

Thetis, daughter of Nereus and Doris , was one of the fifty sea nymphs known as the Nereids —probably the most famous and important of them all. She was highly honored by the Olympians , the most powerful gods of the Greek pantheon, and had once saved Zeus himself from an uprising. She married Peleus , a mortal hero who had distinguished himself as one of the Argonauts, and had a son: the warrior Achilles .

Thetis is best known for her role in the mythology of her son Achilles. Reluctant to accept that her son was mortal and had to die, Thetis did everything in her power to stave off his inevitable death—to no avail. Achilles was ultimately killed while fighting in the Trojan War.

Thetis was an important figure in Greek literature, especially Homer’s Iliad . She was also worshipped in some parts of Greece, and some even believe that she was among the most important goddesses of the Greeks in the earliest periods of their history.

There is some obscurity surrounding the etymology of the name “Thetis” (Greek Θέτις, translit. Thétis ). Both ancient and modern scholars have suggested that the name could be connected to the Greek verb τίθημι ( títhēmi ), meaning “to establish, set up.” [1] But others have interpreted the name “Thetis” as an early doublet or alternate for “ Tethys ,” the name of the Titan goddess who married Oceanus and became closely associated with the sea. [2]

Pronunciation

Titles and epithets.

As a daughter of Nereus, Thetis was a “Nereid” (Νηρηΐς, Nērēḯs ). Individually, Thetis’ most important epithets were ἀργυρόπεζα (argyrópeza, “silver-footed”) and ἁλοσύδνη ( halosýdnē , “sea-born”).

Thetis, like her Nereid sisters, was a beautiful sea nymph. She was honored as a goddess and was immortal. Except for a brief period after her marriage to the mortal Peleus—during which she lived in Peleus’ palace in Phthia in northern Greece—Thetis lived with the other Nereids far below the waves, in the luxurious grotto of Nereus. [3]

Thetis, like her father Nereus, was sometimes thought to have had the power to change her shape at will. She tried to use this power to escape Peleus when he came to claim her as his bride, but was unsuccessful. [4]

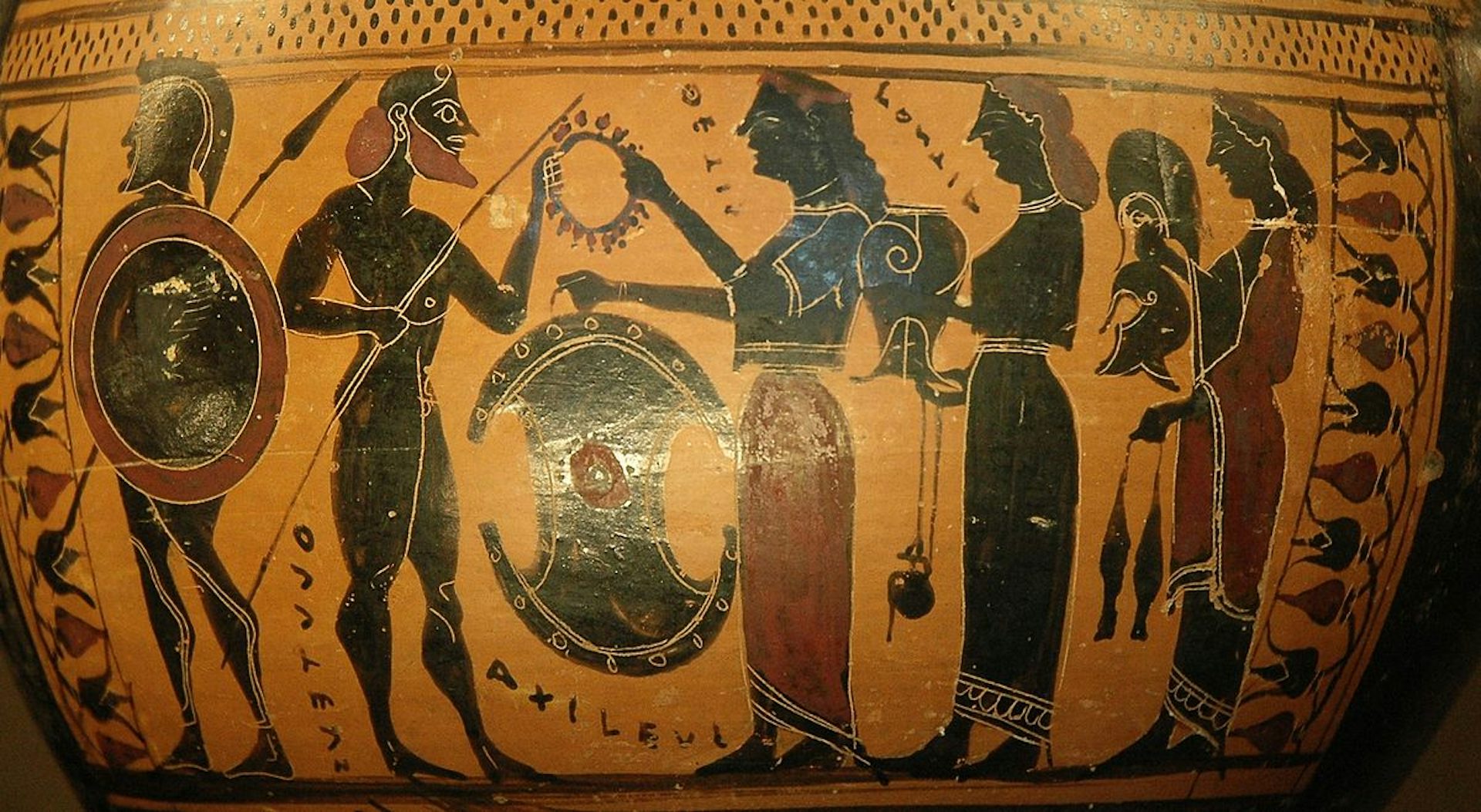

Several scenes from Thetis’ mythology were popular among ancient artists, especially among vase painters of the sixth and fifth centuries BCE. The most common scenes in ancient art were Thetis’ wrestling match with Peleus, her wedding to Peleus, and her presentation of armor to Achilles. [5]

The father of Thetis was Nereus, a son of Gaea and Pontus who was known for his wisdom; her mother was the Oceanid Doris. [6] She was therefore one of the fifty “Nereids,” the sea nymph daughters of Nereus. According to one source, she also had a brother named Nerites, a handsome companion of Poseidon . [7]

Relief sculpture of Nereus, the father of the Nereids, from the Pergamon Altar (2nd century BCE)

But there were other, less familiar traditions about Thetis’ parentage too. In one, Thetis was the daughter of the centaur Chiron , not of Nereus. [8] In another strange account, known only from a fragmentary poem by Alcman, Thetis appears to be one of the first—perhaps even the very first—being to come into existence, together with or just before the abstract personifications Tekmor (“End”) and Poros (“Path”). [9]

Thetis married Peleus, a mortal hero who gained fame as one of the Argonauts, with whom she had a son: Achilles, the greatest hero of the Trojan War. [10]

Thetis was born to the sea gods Nereus and Doris, one of fifty daughters known as the Nereids. She was said to have been raised by Hera , wife of Zeus and queen of the gods. [11] She lived together with her sisters in the depths of the sea, in the palatial grotto of her father Nereus.

Ever since antiquity, Thetis has been considered the most important of the Nereids: ancient sources invoked her “best of the Nereids,” [12] “first of the Nereids,” [13] and so on. Indeed, Thetis had a much more significant role in Greek mythology than any of her sisters (leading some scholars to argue that there was a time when Thetis was a much more central figure in Greek religion).

Thetis and the Gods

In her relationship with the gods, Thetis often took on the role of nurturer or even savior.

In one myth, Thetis kindly nursed Hephaestus back to health after he had been cast out of heaven (there were different versions of who exactly cast Hephaestus out of heaven: it was either Zeus or Hera). [14]

In another, similar myth, Thetis took in the young god Dionysus (or, in some versions, Dionysus’ nurses) when he was fleeing the prosecution of the barbarous Thracian king Lycurgus. As a reward, Dionysus gave Thetis a beautiful urn fashioned by Hephaestus—the urn in which Thetis would someday place the ashes of her son Achilles. [15]

Another time, Thetis saved Zeus himself—the most powerful of the Greek gods. Several of the other Olympians, led by Hera, Poseidon , and Athena , wished to overthrow Zeus and take over his power. While he was sleeping, they bound him in chains. But Thetis summoned Briareus , one of the invincibly strong Hecatoncheires (“Hundred-Handers”) to help Zeus: Briareus broke Zeus’ chains and helped Zeus reassert his dominance. [16]

Illustration by John Flaxman (1795) of a myth recounted in Book 1 of Homer's Iliad : Briareus is summoned by Thetis to help Zeus when the other Olympians try to overthrow him

Thetis and Peleus

Though she was a goddess, Thetis was forced to marry a mortal man, the hero Peleus. This myth was known in a few different forms.

Thetis was so beautiful that Zeus (or, in some versions, both Zeus and Poseidon) wanted to sleep with her. In one version, Thetis refused Zeus’ advances because she did not want to offend his jealous wife Hera; to punish her, Zeus vowed that she would marry a mortal. [17] But in another version, it was revealed by an oracle that Thetis was destined to have a son who would be stronger than his father—the last thing a god wanted (when a god had a son who was stronger than they were, that son usually ended up overthrowing their father); to prevent turmoil in heaven, it was decided that Thetis must marry a mortal. [18]

Eventually, Peleus was chosen as a suitable match for Thetis. Though a mortal, Peleus had an impressive lineage—his grandfather was Zeus—and he had a distinguished career as a hero, having sailed with the Argonauts and taken part in the Calydonian Boar Hunt. But before he could marry Thetis, Peleus had to capture her. He found her in a cave and grabbed her. Thetis transformed herself into different shapes in an effort to escape, but Peleus managed to hold on and thus won Thetis as his bride. [19] Thetis and Peleus were married in a lavish wedding, attended by all the great gods and mortals. [20]

Detail from an Attic red-figure kylix showing Peleus capturing Thetis as she changes shape, attributed to Douris (ca. 490 BCE)

There were also other, lesser known traditions about Thetis and Peleus. In one, it was Thetis who pursued Peleus rather than the other way around; [21] in another, Peleus’ wife was not the goddess Thetis but a mortal of the same name; [22] and in another, Peleus was actually married to the mortal Philomela (daughter of the Myrmidon warrior Actor), and his marriage to Thetis was simply a rumor started by the centaur Chiron. [23]

The Birth of Achilles

Thetis could not make peace with the fact that any children she had would be mortals doomed to die; in some traditions, Thetis learned from a prophecy that her son was destined to die in battle. [24]

Thetis went to dramatic lengths to save her son from his inevitable doom. In some traditions, she would throw her children by Peleus into a cauldron of boiling water or fire to test whether they were mortal, killing them all except Achilles, who was saved by Peleus. [25] In other traditions, Thetis tried to make the baby Achilles immortal by either anointing him in ambrosia and putting him into fire [26] or by dipping him into the river Styx. [27]

Thetis Dipping the Infant Achilles into the River Styx by Peter Paul Rubens (1630–1635)

In any case, Thetis failed to make her son immortal, either because Peleus walked in on her and caused her to let go of the child before she could complete the process or, alternatively, because the boy remained vulnerable in the part of his body from which Thetis held him—his heel.

In most traditions, Thetis left Peleus soon after the birth of Achilles, unwilling to live as the wife of a mortal or angry at Peleus for interfering with her attempts to make her child immortal. [28] In what became the dominant tradition, Peleus then sent Achilles to be raised and trained by the centaur Chiron. [29]

The Trojan War

When the Greeks were preparing to attack the city of Troy— Helen , the wife of one of the Greek kings, had been carried off by the Trojan prince Paris and the Greeks were bent on getting her back—Thetis wanted desperately to make sure her son Achilles would not fight and die in the war.

In one famous myth, Thetis (or Peleus in some versions) disguised the young Achilles as a girl and sent him to live with the daughters of Lycomedes, the king of the small Aegean island of Skyros. But the clever Greek king Odysseus eventually managed to find Achilles and trick him to come out of hiding. So in the end, Thetis’ plan failed and Achilles joined the Greek army in their war against Troy. [30]

Thetis continued protecting and helping Achilles throughout the Trojan War, even though she knew he was doomed to die. When Agamemnon , the commander-in-chief of the Greek army, insulted Achilles in the ninth year of the war, Achilles vowed to leave the fighting. He asked Thetis to ask Zeus to let the Trojans get the better of the Greeks for a while so that the Greeks would suffer for not giving him the honor he deserved. Thetis did as Achilles asked and Zeus agreed to help. [31]

Jupiter and Thetis by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1811)

Soon afterwards, Achilles' best friend Patroclus went into battle wearing Achilles’ armor and was killed by Hector , the crown prince of Troy and the greatest of the Trojan heroes. Achilles was consumed by grief. Thetis, accompanied by the other Nereids, came to comfort Achilles and mourn with him. She revealed to Achilles that if he tried to avenge Patroclus by fighting Hector, his fate would be sealed: he would die in battle. But when Achilles made it clear that he would not change his mind about returning to the fighting, Thetis promised she would bring Achilles new armor and weapons forged by Hephaestus. [32]

After Thetis brought Achilles his new suit of armor, Achilles marched into battle and killed Hector. [33] Achilles then dishonored Hector’s body for days, until Thetis warned him that the gods had commanded him to return the body to Troy for a proper funeral; Priam, Hector’s father and the king of Troy, came into the camp for the body and Achilles turned it over to him. [34]

Detail from an Attic black-figure hydria showing Thetis and her attendants (right) presenting Achilles (left) with armor (ca. 575–550 BCE)

Thetis continued to help Achilles after the death of Hector. For example, she interceded with Zeus on his behalf when he fought the Ethiopian hero Memnon , who had come to help the Trojans. [35] But soon Achilles fell in battle, just as had been predicted. In the familiar tradition, he was shot in the heel with an arrow shot by Hector’s brother Paris and guided by the god Apollo himself. Thetis and the other Nereids came to help bury and mourn Achilles. [36]

In some traditions, Thetis ultimately had her way and managed to make Achilles immortal, in a sense. After the hero was killed, she took him to the Isles of the Blessed, sometimes also called Leuce or Elysium. There, Achilles lived in eternal bliss with other great heroes and demigods. Some said that there he married the beautiful witch Medea or even Helen. [37]

Other Myths

Though most of Thetis’ mythology surrounded her role as wife of Peleus and mother of Achilles, there were other myths about her too.

In one myth, Thetis and the Nereids helped the Argonauts sail through the Planctae, the “Wandering Rocks,” which crushed most ships that passed through them. [38]

Another myth, found in Ovid’s Metamorphoses , involved Thetis’ husband Peleus. Psamathe—a Nereid and thus one of Thetis’ sisters—wanted to punish Peleus for killing her son Phocus. She sent a monstrous wolf to attack Peleus’ lands and devour his herds. Peleus begged Thetis for help, and Thetis managed to convince her sister to forgive Peleus. [39]

Other myths involved Thetis’ role in the homecoming of the Greeks who had fought at Troy. After the Greeks sacked Troy, Thetis warned Neoptolemus, her grandson, to sacrifice to the gods before sailing home. He and those who stayed with him were able to get home safely, but those who left without sacrificing suffered terrible storms. [40] Some were even shipwrecked and killed—one of these casualties, the hero Ajax the Lesser, was said to have been buried by Thetis herself. [41]

In one strange, little known tradition, Thetis blamed the death of her son Achilles on Helen, who helped cause the Trojan War by running off with the Trojan Paris. Thetis punished Helen—according to Ptolemy Hephaestion at least—by transforming her into a seal after the war was over. [42]

Another obscure myth—also found in the work of Ptolemy Hephaestion—told of how the witch Medea challenged Thetis to a beauty contest. When the Cretan hero Idomeneus judged the contest in Thetis’ favor, Medea was so enraged that she cursed Idomeneus: claiming that his judgment was false, she made him incapable of ever telling the truth. [43]

Thetis was worshiped in some parts of Greece. There is evidence that she had cults in Sparta, [44] Thessaly, [45] and Pharsalus. [46] Her Spartan cult seems to have been particularly important: it was centered around an archaic temple called a Thetideion that contained a wooden cult image of the goddess said to be even more ancient than the temple itself.

Though Thetis was a minor goddess by the Classical Period of Greek history (ca. 490–323 BCE), it is possible that she was a much more important deity before then. For example, she plays a remarkably important role in the Iliad , which was put into writing around 750 BCE. Even more intriguing is a fragment from a poem by Alcman, who lived in Sparta in the seventh century BCE: here, Thetis appears to be named as the first being to come into existence and as one of the creators of the cosmos. [47]

Pop Culture

Thetis continues to appear in some modern adaptations of Greek myths, especially the myths of the Trojan War. Thetis has been a character in films such as Clash of the Titans (1981) and Troy (2004). In the latter, she is reimagined as a priestess rather than as an actual goddess.

Thetis also features in Madeline Miller’s 2011 novel, The Song of Achilles . She is portrayed as a cold character who has a strained relationship with her son Achilles and who strongly disapproves of Achilles friend (and lover) Patroclus.

Thesis The Greek Primordial Goddess of Creation

In Greek mythology , Thesis is the primordial goddess of creation , often associated with the concept of Physis (Mother Nature). She is believed to have emerged at the beginning of creation alongside Hydros (the Primordial Waters) and Mud. Thesis is sometimes portrayed as the female aspect of the first-born deity, Phanes. She holds a significant role in ancient cosmology and mythology’s origins.

Key Takeaways:

- Thesis is the Greek primordial goddess of creation in ancient Greek mythology .

- She is associated with Physis (Mother Nature) and emerged alongside Hydros and Mud at the beginning of creation .

- Thesis may be considered the female aspect of the first-born deity, Phanes.

- She embodies the concept of creation and plays a vital role in ancient cosmology .

- Thesis’s origins, family connections, and powers contribute to her importance as a mythological figure .

Origins of Thesis

Thesis, the Greek primordial goddess of creation , holds a significant place in Greek mythology and ancient cosmology . As the first being to emerge at the creation of the universe, she embodies the concept of the birth of the cosmos. Thesis is closely associated with Hydros and Mud, representing the elemental forces of water and earth, respectively. Some interpretations suggest that she is the female aspect of Phanes, a bi-gendered deity symbolizing the essence of life.

In the Orphic Theogonies, Thesis is prominently mentioned as the initial manifestation of creation. This mythological text provides insights into her role in the ancient Greek pantheon. As the Greek primordial goddess of creation , Thesis sets the foundation for the entire mythological framework and cosmological understanding of the ancient Greeks.

Family of Thesis

As a primordial goddess , Thesis does not have traditional parents. She is considered to have spontaneously emerged at the beginning of creation. However, she is associated with several important beings in Greek mythology.

- Hydros: The primordial god of water, is mentioned as a possible parent of Thesis. Together, they represent the fundamental elements of creation, water and earth.

- Mud: Another possible parent of Thesis, Mud symbolizes the primordial nature of the earth.

- Chronos: Thesis is connected to the birth of Chronos, the primordial god of time. This relationship highlights her role as a progenitor of important deities.

- Ananke: Thesis is also associated with Ananke, the primordial goddess of necessity. This connection further underscores her significance in the realm of Greek primordial gods .

These relationships highlight Thesis’s role in the family tree of primordial gods , emphasizing her importance as a foundational figure in Greek mythology.

Powers and Attributes of Thesis

As the Greek primordial goddess of creation, Thesis possesses a range of impressive powers and attributes. Her divine nature grants her omnipresence , meaning that she pervades every aspect of the universe. She exists in all places simultaneously, her essence intertwined with the fabric of reality.

Moreover, Thesis is blessed with omniscience . From the moment of creation, she has witnessed and comprehended every event that has unfolded in the cosmos. Her vast knowledge encompasses the intricate details of the universe, past, present, and future.

Thesis’s creative abilities are truly awe-inspiring. With a mere thought, she has the power to shape existence, bringing forth life and shaping the destiny of all beings. From the grandest celestial bodies to the tiniest microorganisms, Thesis can conjure them effortlessly out of nothingness.

Although Thesis is an ethereal being, she can manifest a physical form at will. She can assume any appearance, captivating mortals and immortals alike with her divine beauty and grace. This ability allows her to interact with the world and its inhabitants on a more tangible level, if she desires.

It is also crucial to note that Thesis transcends the constraints of mortality. As a primordial deity , she exists beyond the boundaries of time and the cycle of life and death. Her essence is eternal, sustaining the very essence of creation itself.

Role in Creation and Mythology

Thesis, the Greek primordial goddess , played a significant role in the creation of the cosmos. She is believed to have created a cosmic egg from water, which served as the vessel for the emergence of the first-born deity, Phanes. Phanes, also known as Life, became the first king of the universe and the ancestor of all other living beings.

Thesis is considered the mother of Hydros, the grandmother of Phanes, and the creator of the cosmic egg . Her involvement in the creation of life and the universe establishes her as a foundational figure in Greek mythology, symbolizing the origins of all living beings.

Mystery and Interpretations of Thesis

Despite her significant role in Greek mythology and ancient cosmology, much remains unknown about Thesis, the primordial goddess of creation. She remains a mysterious figure, with limited records and descriptions. Yet, the enigmatic nature of Thesis only adds to her allure and intrigue.

Thesis is often depicted as an ethereal being, capable of shape-shifting and assuming various forms. While she is typically referred to with female pronouns, it is believed that she has the ability to change her gender at will, further adding to the mystique surrounding her.

One prevailing theory suggests that Thesis, along with other primordial deities , has chosen to cast aside her anthropomorphized form. This deliberate act of transcendence may explain the scarcity of information and records about her existence. It is as if Thesis embodies the essence of creation itself, transcending human comprehension and defying categorization.

“Thesis, with her shape-shifting abilities, seems to elude our understanding, much like the very essence of creation she represents.”

Despite the lack of concrete information about Thesis, scholars and myth enthusiasts continue to speculate and interpret her character and motivations. Some theories delve into the metaphysical aspects of creation, linking Thesis to the concept of thesis as an idea or proposition that initiates the birth of new understanding.

In the absence of concrete facts, we are left to contemplate the elusive nature of this ancient deity. Perhaps the true essence of Thesis lies not in predefined descriptions and accounts but in the layers of interpretation and imagination that continue to unfold as we explore the depths of Greek mythology and the primordial deities .

Ethymology of Thesis

The word “thesis” comes from the Greek term “θέσις” (thésis), which means “a setting, a position, or a proposition.” This etymology further emphasizes the underlying connection between Thesis and the concept of creation, as she is the very embodiment of the initiating force behind the birth of the cosmos.

Comparative Analysis of Primordial Deities

Influence and legacy of thesis.

Thesis, the primordial goddess of creation in Greek mythology, had a profound influence on the cosmology and origins of mythology itself. As the embodiment of creation, she played a pivotal role in shaping the universe and the emergence of life. Her legacy as a revered deity continues to resonate in ancient Greek culture.

One of Thesis’s significant contributions to Greek mythology was her creation of the cosmic egg . This cosmic egg served as the vessel from which Phanes, the first-born deity and embodiment of life, emerged. Symbolizing the origins of all living beings, the birth of Phanes represents the intrinsic connection between Thesis and the creation of life.

“Thesis, as the primordial goddess of creation, brought forth the cosmic egg, giving birth to the first deity and the essence of life itself.” – Greek Mythologist

Thesis’s presence in Greek mythology reinforces her importance as a divine being and one of the ancient deities revered by the ancient Greeks. As the primordial goddess of creation, she not only birthed the universe but also established the foundation for the ancient Greek cosmology .

Her legacy extends beyond Greek mythology, influencing the understanding and interpretation of creation in various cultures and religious beliefs. Thesis’s role as a creation deity highlights her significance and enduring influence, shaping the understanding of cosmology and the origins of existence.

Thesis’s influence and legacy continue to captivate scholars, historians, and enthusiasts who dive into the depths of Greek mythology. As one of the foundational figures in ancient Greek cosmology , she continues to inspire and provoke thoughtful analysis of the origins of existence and the ancient Greek understanding of creation. Thesis’s impact on mythology remains an enduring testament to her role as a primordial goddess.

The Primordial Goddess in Ancient Cosmology

In ancient Greek cosmology , Thesis occupies a significant role as the primordial goddess of creation. Rooted in the belief systems of ancient Greece, the concept of the cosmos emerging from primordial elements and beings is central to understanding the origins and structure of the world. Thesis represents the initial manifestation of creation, symbolizing the birth of life and the universe itself.

Within the framework of ancient creation beliefs , Thesis’s presence is instrumental in explaining the emergence of the cosmos. As a primordial deity , she embodies the primal forces that form the foundation of all existence. Her significance lies in her ability to symbolize the birth of life and the universe, delineating the beginnings of Greek cosmology.

“Thesis represents the initiation of creation, a symbol of the universe’s birth and the formation of life itself.” – Greek Scholar

Exploring the Primordial Deity

As a primordial deity , Thesis has a unique place in ancient Greek cosmology. She is considered a divine figure of immense power and influence, integral to the very fabric of the universe. While her character and motivations are often shrouded in mystery, her role as a primordial deity reflects the ancient Greeks’ understanding of creation and the forces that govern the cosmos.

Thesis’s presence in ancient cosmology highlights the importance of primordial deities in ancient Greek mythology and belief systems. These deities represent the fundamental aspects of the universe, embodying the elemental forces that shape reality. As the primordial goddess of creation, Thesis serves as a powerful symbol of the origins and structure of the world.

The Significance of Thesis in Ancient Greek Beliefs

Thesis’s role as the primordial goddess of creation aligns with ancient Greek beliefs regarding the origins of the universe. According to these ancient creation beliefs , the cosmos arose from a primordial state, with Thesis symbolizing the emergence of life and the birth of the universe.

Within the ancient Greek cosmological framework, Thesis’s presence signifies the beginning of existence and the formation of the natural world. She represents the creative force that brings order and structure to the chaotic primordial state, establishing the foundations upon which all subsequent beings and phenomena would arise.

Thesis’s presence in ancient Greek cosmology provides insight into the ancient Greeks’ understanding of the universe and their attempts to explain its formation. Her role as the primordial goddess of creation underscores the importance of divine beings in shaping the beliefs and worldview of the ancient Greeks.

Reflections in Literature and Mythology

References to Thesis can be found in various ancient literary works and mythological texts. Homer, in the Iliad , depicts Okeanos and Tethys (another name for Thesis) as the primordial gods of creation. Alcman describes Thesis as the first being to emerge, followed by Chronos and Ananke. Plato mentions Thesis as the mother of Eros (Procreation). These references point to the significance of Thesis in ancient Greek literature and mythology, solidifying her role as a mythological figure .

Speculations and Interpretations

Due to the limited information available about Thesis, speculation and interpretation surround her character and motivations. Some theories suggest that she was one of the first deities to cast aside her anthropomorphic form, leading to the scarcity of records about her. Others delve into the metaphysical aspects of creation and thesis as a concept. These speculations highlight the intrigue and fascination surrounding this enigmatic Greek primordial goddess.

Modern Influence and Popularity

While Thesis may not enjoy the same level of recognition as other Greek mythological figures, her significance resonates within the realm of mythological studies. Scholars and enthusiasts continue to explore and interpret her role in creation and mythology. Additionally, her portrayal in ancient texts and her connection to primordial deities contribute to the ongoing fascination with Greek mythology. Thesis’s presence in the realm of mythological characters remains intriguing to modern audiences.

Thesis, the Greek primordial goddess of creation, holds a prominent position in Greek mythology and ancient cosmology. As the embodiment of creation, she is intricately connected to the birth of the universe, the emergence of life, and the formation of deities. Although shrouded in mystery, her role as a foundational figure in Greek mythology and ancient beliefs is undeniable. Thesis’s influence and legacy continue to be explored and interpreted, captivating those who delve into the rich tapestry of ancient myth and lore.

Who is Thesis in Greek mythology?

Thesis is the primordial goddess of creation, often associated with the concept of Physis (Mother Nature). She is believed to have emerged at the beginning of creation alongside Hydros (the Primordial Waters) and Mud.

What role does Thesis play in ancient cosmology?

Thesis represents the initial manifestation of creation, symbolizing the emergence of life and the universe. Her presence in ancient cosmology underscores the significance of the primordial deities in explaining the origins and structure of the world.

Who are the possible parents of Thesis?

Thesis is associated with Hydros, the primordial god of water, and Mud. She is also connected to the birth of Chronos, the primordial god of time, and Ananke, the primordial goddess of necessity.

What powers and attributes does Thesis possess?

Thesis is omnipresent, omniscient, and has the ability to create anything from nothing. She can manifest a physical form when desired and exists outside the limitations of mortality as a primordial deity.

What is the role of Thesis in the creation of the cosmos?

Thesis created a cosmic egg from water, from which the first-born deity, Phanes, emerged. Phanes became the first king of the universe and ancestor to all other living beings.

Why is there limited information about Thesis?

Thesis remains a mysterious figure with limited records and descriptions. It is believed that she, like other primordial deities, has chosen to cast aside her anthropomorphized form, leading to a lack of information about her existence.

What is the legacy of Thesis in Greek mythology?

As the primordial goddess of creation, Thesis holds a prominent position in Greek mythology and ancient cosmology. She embodies the concept of the birth of the universe and the subsequent emergence of life, establishing her as a foundational figure.

How is Thesis portrayed in ancient literature and mythology?

References to Thesis can be found in various ancient literary works and mythological texts, including those by Homer, Alcman, and Plato. These references solidify her role as a mythological figure in ancient Greek literature and mythology.

What are the speculations and interpretations surrounding Thesis?

Due to limited information, there are speculations about Thesis’s motivations and character. Some theories suggest that she was one of the first deities to cast aside her anthropomorphic form, leading to the scarcity of records about her.

Does Thesis have modern influence and popularity?

While Thesis may not enjoy the same level of recognition as other Greek mythological figures, her significance resonates within the realm of mythological studies. Scholars and enthusiasts continue to explore her role in creation and mythology.

What is the role of the primordial goddess in ancient cosmology?

In ancient Greek cosmology, the primordial goddess represents the initial manifestation of creation, symbolizing the emergence of life and the universe. She is intricately connected to the birth of the cosmos and the formation of deities.

How does Thesis’s influence extend beyond her existence in Greek mythology?

Thesis’s role as the primordial goddess of creation aligns with ancient Greek cosmology. Her presence in ancient creation beliefs highlights the significance of the primordial deities in explaining the origins and structure of the world.

What is the significance of Thesis in ancient mythology and cosmology?

As the Greek primordial goddess of creation, Thesis played a prominent role in the formation of the cosmos and the emergence of life. Her importance as a divine being and one of the ancient deities revered by the Greeks cannot be overlooked.

Source Links

- https://www.theoi.com/Protogenos/Thesis.html

- https://superhuman-characters-and-their-powers.fandom.com/wiki/Thesis_(Greek_Mythology)

- https://www.worldanvil.com/w/a-world-of-myth-and-magic-power-of-a-name/a/thesis3A-primordial-goddess-of-creation-person

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

MythologySource

- What Were the Hamadryads in Greek Mythology?

- The Hades and Persephone Story

- Was the Griffin a Bird from Greek Mythology?

Thetis and Zeus

Thetis was the second goddess to be rejected by Zeus because he feared the power of her son. She didn’t give birth to a god, though; Thetis was the mother of a glorious hero!

Thetis was not one of the major goddesses of the Greek pantheon. Considering her status, her impact on mythology was oversized.

The one-time fiancee of Zeus was a protective goddess who saved the lives of many Olympic gods. According to Homer, one of these was Zeus himself.

Her wedding feast as a joyous occasion, but the exclusion of Eris from the guest list led to the beginning of the Trojan War and Thetis’s greatest personal tragedy.

Her influence was so great that she was able to convince Zeus, the famously rigid king of the gods, to change his mind in her favor. While it did not save her son’s life, the story of Zeus and Thetis does show that the protective Nereid may have once been more than she seemed.

Zeus Avoided Marriage Thetis

Thetis is usually seen as a fairly minor goddess in Greek mythology, but one whose life was intertwined with many major events.

Thetis was usually described as a water goddess, often a Nereid. She was also meant to be Zeus’s second wife.

Zeus married the Titaness Metis, but swallowed her when he learned that she would one day have a son who would overthrow him. Shortly afterward, he began to be interested in Thetis.

Before he could act on this attraction, however, he heard a similar prophecy regarding his new paramour. Thetis, too, was fated to one day give birth to a son who would be more powerful and famous than his father.

Zeus did not want to risk following in the footsteps of both his father and grandfather by being violently overthrown. To maintain his power, he abandoned Thetis and married Hera instead.

Thetis ended up not become the mother of Zeus’s child, but the foster mother of Hera’s. She and the ocean nymphs found Hephaestus when he was cast down from Olympus and raised him on earth.

Many times, Thetis came to the rescue of the gods. When Dionysus was expelled from Thrace, for example, Thetis hid him in a bed of seaweed.

She was most famous, however, for her role in human affairs rather than those of the gods.

Zeus eventually determined that the prophecy surrounding Thetis was too dangerous for any of the gods to risk marrying her. Instead, he arranged for her to be married to a mortal man.

Peleus was a great hero and because Thetis was well-loved by the Olympians the wedding was among the most elaborate feasts ever held on Mount Olympus. The only goddess who was not invited was Eris , the personification of discord.

The exclusion of the goddess of strife from the wedding prompted her to seek revenge on the Olympians for slighting her. She sent a golden apple addressed to the fairest goddess of Olympus and the resulting infighting among the goddesses helped to ignite the Trojan War.

Her involvement in the war went beyond its beginnings, however. Thetis became heavily involved in the conflict because her son with Peleus, Achilles, was one of the fighters.

Thetis attempted to protect her son by burning away his mortality, but Peleus stopped her because he believed she was hurting the baby. According to some legends, Achilles was left with a single vulnerability on the heel where his mother had held him.

Throughout the war, Thetis attempted to intervene to keep her son safe. She even went directly to Zeus to ask him to intercede on behalf of Achilles.

Homer’s Iliad is the only source that includes the leverage a minor goddess could use to sway the will of the king of the gods. According to the poet, the gods of Olympus had once rebelled against Zeus and Thetis had been the one to save him.

Hera, Poseidon, and Athena had put the king of the gods in chains in an attempted coup. Thetis had summoned a hundred-armed giant to break the chains and restore Zeus to power.

Homer may have believed that Zeus owed his throne to Thetis, but her requests did little good. As a prophecy had foretold, her son lived a short but glorious life and fell in battle during the Trojan War.

My Modern Interpretation

Thetis was unusual for the nymphs in the major role she played in shaping the outcome of many myths. She rescued many gods, mothered a great hero, nearly married the king of Olympus, and her marriage directly led to the beginning of the Trojan War.

Some historians see this role as evidence that Thetis was once a more powerful goddess in a pre-classical tradition.

It is possible that Thetis was a double of Tethys, the Titan goddess of the sea. The two may have once been the same entity, but developed separate mythologies and names over time.

The story of her engagement to Peleus also has aspects of more ancient sea gods. Like The Old Man of the Sea, Thetis was a shapshifter who could only be captured by someone able to hold on as she turned into a variety of bestial and monstrous creatures.

That would explain how Thetis was more prominent and powerful than most other nymphs, but her interactions with Zeus also show that she may have held greater power in the pre-literate past.

Her most prominent role is in the works of Homer, who was also one of the first poets to write down the Greek legends. Because of the style in which he wrote and his early date, Homer’s poems often seem to reflect older versions of well-known stories.

In the Iliad , Thetis is a powerful enough goddess to bend Zeus to her will. When she makes a request of the king of the gods, he changes his position to please her.

Homer attributes this in part to the fact that Thetis had saved his life and throne. Just as Metis had helped him defeat Cronus, Thetis helped him hold on to power.

The parallels between these suggest that this may have been a motif throughout the early Greek world. Different traditions existed of Zeus marrying, then discarding, an older goddess who had given him aid but whose son would be a threat to him.

In the Iliad Thetis had to go to Zeus to ask for her son to be protected. While Homer showed Thetis in a central role, this seems contrary to her appearances in other stories.

Thetis was consistently portrayed as a savior of the gods. On at least three occasions she protected or nursed one of the Olympians when they were at their most vulnerable.

This may indicate that in earlier myths Thetis was a protective goddess. By the time of Homer she was still well-regarded, but her position had declined enough that she had to ask Zeus for protection instead of providing it herself.

Thetis was meant to be the second wife of Zeus, but the engagement was abandoned when he learned that her son would one day be more powerful than his father.

To prevent the threat to any of the other gods, he had Thetis married to a human. Peleus was a heroic general, but his fame was far surpassed by their son, Achilles.

Thetis was usually cast in the role of a protective goddess, which could be a holdover from an earlier belief system. At least three stories describe her sheltering or freeing vulnerable Olympians.

She was not successful, however, in protecting her own son. Achilles died in the final days of the Trojan War despite his mother’s attempts to shield him from harm.

Thetis had even gone so far as to implore Zeus for aid, showing herself to be one of the few deities who could turn the god’s opinion in her favor. Homer alone explains that this deference was because Thetis had once freed the king of the gods when the other members of his family had attempted a rebellion.

The interactions between Thetis and Zeus seem to show that she was once a more powerful goddess of protection than she was later believed to be. Before the time of Homer, it was Zeus who asked for aid from Thetis instead of the other way around.

My name is Mike and for as long as I can remember (too long!) I have been in love with all things related to Mythology. I am the owner and chief researcher at this site. My work has also been published on Buzzfeed and most recently in Time magazine. Please like and share this article if you found it useful.

More in Greek

Thero: the beastly nymph.

The people of Sparta claimed that Ares had been nursed by a nymph called Thero. Does...

Who Was Nomia in Greek Mythology?

Some nymphs in Greek mythology were famous, but others were only known in a certain time...

Connect With Us

- View history

is a primordial goddess of creation in ancient Greek religion. She is sometimes thought to be the child of Khaos, and emerged with Hydros. It is believed that she and her sibling created the world Gaia and the waters that surround her, or either that cooperated with Khaos in the process.

Parents [ ]

Ancient text [ ].

Thesis (goddess)

- View history

Thesis ( Greek Θέσις ; Thesis ) is a primordial goddess of creation in ancient Greek religion. [1] She is sometimes thought to be the child of Chaos , and emerged with Hydros . It is believed that she and her sibling created the world Gaia and the waters that surround her, or either that cooperated with Chaos in the process. She is sometimes identified with Physis .

See also [ ]

References [ ].

- ↑ http://www.theoi.com/Protogenos/Thesis.html

Thesis Greek God

Enshrined in ancient lore as the god of creation and the personification of divine order and natural law, Thesis occupies a significant position in the intricate pantheon of Hellenic deities, casting a profound and enduring influence on the philosophical and artistic currents that have flowed through human history.

The name “Thesis” finds its etymological roots in the Greek term “thésis,” meaning “a proposition” or “a setting down.” This linguistic connection serves as a poignant reflection of Thesis’s paramount role in laying down the fundamental principles that govern the cosmos, establishing the bedrock upon which the intricate complexities of life and existence unfold. Often depicted as a majestic figure adorned in regal attire, with a countenance exuding wisdom and authority, Thesis symbolizes the inherent balance and harmony that underlie the intricate tapestry of the natural world.

Central to Thesis’s divine essence is the concept of cosmic order, an intricate web of interconnected forces that govern the ebb and flow of existence. As the divine architect of the universe, he is credited with orchestrating the harmonious interplay of elements, guiding the celestial bodies in their celestial dance and imbuing the natural world with an inherent sense of purpose and design. Through his unwavering commitment to balance and equilibrium, Thesis represents the philosophical underpinnings that have shaped humanity’s understanding of the delicate interplay between order and chaos, form and void.

In the annals of Greek mythology, Thesis’s influence extends far beyond the realm of celestial mechanics, permeating various aspects of human civilization, from the realms of art and literature to the spheres of governance and jurisprudence. His essence embodies the inherent desire for structure and coherence that lies at the heart of human endeavors, inspiring generations of thinkers and visionaries to seek out patterns and meaning within the complex tapestry of existence.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Theseus, hero of athens.

Terracotta amphora (jar)

Signed by Taleides as potter

Terracotta kylix: eye-cup (drinking cup)

Terracotta lekythos (oil flask)

Attributed to the Diosphos Painter

Terracotta kylix (drinking cup)

Attributed to the Briseis Painter

Terracotta calyx-krater (bowl for mixing wine and water)

Attributed to a painter of the Group of Polygnotos

Terracotta Nolan neck-amphora (jar)

Attributed to the Dwarf Painter

Attributed to the Eretria Painter

Marble sarcophagus with garlands and the myth of Theseus and Ariadne

Andrew Greene Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

August 2009

In the ancient Greek world, myth functioned as a method of both recording history and providing precedent for political programs. While today the word “myth” is almost synonymous with “fiction,” in antiquity, myth was an alternate form of reality . Thus, the rise of Theseus as the national hero of Athens, evident in the evolution of his iconography in Athenian art, was a result of a number of historical and political developments that occurred during the sixth and fifth centuries B.C.

Myth surrounding Theseus suggests that he lived during the Late Bronze Age, probably a generation before the Homeric heroes of the Trojan War. The earliest references to the hero come from the Iliad and the Odyssey , the Homeric epics of the early eighth century B.C. Theseus’ most significant achievement was the Synoikismos, the unification of the twelve demes, or local settlements of Attica, into the political and economic entity that became Athens.

Theseus’ life can be divided into two distinct periods, as a youth and as king of Athens . Aegeus, king of Athens, and the sea god Poseidon ( 53.11.4 ) both slept with Theseus’ mother, Aithra, on the same night, supplying Theseus with both divine and royal lineage. Theseus was born in Aithra’s home city of Troezen, located in the Peloponnesos , but as an adolescent he traveled around the Saronic Gulf via Epidauros, the Isthmus of Corinth, Krommyon, the Megarian Cliffs, and Eleusis before finally reaching Athens. Along the way he encountered and dispatched six legendary brigands notorious for attacking travelers.

Upon arriving in Athens, Theseus was recognized by his stepmother, Medea, who considered him a threat to her power. Medea attempted to dispatch Theseus by poisoning him, conspiring to ambush him with the Pallantidae Giants, and by sending him to face the Marathonian Bull ( 56.171.48 ).

Likely the most famous of Theseus’ deeds was the slaying of the Minotaur ( 64.300 ; 47.11.5 ; 09.221.39 ). Athens was forced to pay an annual tribute of seven maidens and seven youths to King Minos of Crete to feed the Minotaur, half man, half bull, that inhabited the labyrinthine palace of Minos at Knossos. Theseus, determined to end Minoan dominance, volunteered to be one of the sacrificial youths. On Crete, Theseus seduced Minos’ daughter, Ariadne, who conspired to help him kill the Minotaur and escape by giving him a ball of yarn to unroll as he moved throughout the labyrinth ( 90.12a,b ). Theseus managed to flee Crete with Ariadne, but then abandoned her on the island of Naxos during the voyage back to Athens. King Aegeus had told Theseus that upon returning to Athens, he was to fly a white sail if he had triumphed over the Minotaur, and to instruct the crew to raise a black sail if he had been killed. Theseus, forgetting his father’s direction, flew a black sail as he returned. Aegeus, in his grief, threw himself from the cliff at Cape Sounion into the Aegean, making Theseus the new king of Athens and giving the sea its name.

There is but a sketchy picture of Theseus’ deeds in later life, gleaned from brief literary references of the early Archaic period , mostly from fragmentary works by lyric poets. Theseus embarked on a number of expeditions with his close friend Peirithoos, the king of the Lapith tribe from Thessaly in northern Greece. He also undertook an expedition against the Amazons, in some versions with Herakles , and kidnapped their queen Antiope, whom he subsequently married ( 31.11.13 ; 56.171.42 ). Enraged by this, the Amazons laid siege to Athens, an event that became popular in later artistic representations.

There are certain aspects of the myth of Theseus that were clearly modeled on the more prominent hero Herakles during the early sixth century B.C. Theseus’s encounter with the brigands parallels Herakles’ six deeds in the northern Peloponnesos. Theseus’ capture of the Marathonian Bull mirrors Herakles’ struggle with the Cretan Bull. There also seems to be some conflation of the two since they both partook in an Amazonomachy and a Centauromachy. Both heroes additionally have links to Athena and similarly complex parentage with mortal mothers and divine fathers.

However, while Herakles’ life appears to be a string of continuous heroic deeds, Theseus’ life represents that of a real person, one involving change and maturation. Theseus became king and therefore part of the historical lineage of Athens, whereas Herakles remained free from any geographical ties, probably the reason that he was able to become the Panhellenic hero. Ultimately, as indicated by the development of heroic iconography in Athens, Herakles was superseded by Theseus because he provided a much more complex and local hero for Athens.

The earliest extant representation of Theseus in art appears on the François Vase located in Florence, dated to about 570 B.C. This famous black-figure krater shows Theseus during the Cretan episode, and is one of a small number of representations of Theseus dated before 540 B.C. Between 540 and 525 B.C. , there was a large increase in the production of images of Theseus, though they were limited almost entirely to painted pottery and mainly showed Theseus as heroic slayer of the Minotaur ( 09.221.39 ; 64.300 ). Around 525 B.C. , the iconography of Theseus became more diverse and focused on the cycle of deeds involving the brigands and the abduction of Antiope. Between 490 and 480 B.C. , interest centered on scenes of the Amazonomachy and less prominent myths such as Theseus’ visit to Poseidon’s palace ( 53.11.4 ). The episode is treated in a work by the lyric poet Bacchylides. Between 450 and 430 B.C. , there was a decline in representations of the hero on vases; however, representations in other media increase. In the mid-fifth century B.C. , youthful deeds of Theseus were placed in the metopes of the Parthenon and the Hephaisteion, the temple overlooking the Agora of Athens. Additionally, the shield of Athena Parthenos, the monumental chryselephantine cult statue in the interior of the Parthenon, featured an Amazonomachy that included Theseus.

The rise in prominence of Theseus in Athenian consciousness shows an obvious correlation with historical events and particular political agendas. In the early to mid-sixth century B.C. , the Athenian ruler Solon (ca. 638–558 B.C. ) made a first attempt at introducing democracy. It is worth noting that Athenian democracy was not equivalent to the modern notion; rather, it widened political involvement to a larger swath of the male Athenian population. Nonetheless, the beginnings of this sort of government could easily draw on the Synoikismos as a precedent, giving Solon cause to elevate the importance of Theseus. Additionally, there were a large number of correspondences between myth and historical events of this period. As king, Theseus captured the city of Eleusis from Megara and placed the boundary stone at the Isthmus of Corinth, a midpoint between Athens and its enemy. Domestically, Theseus opened Athens to foreigners and established the Panathenaia, the most important religious festival of the city. Historically, Solon also opened the city to outsiders and heightened the importance of the Panathenaia around 566 B.C.

When the tyrant Peisistratos seized power in 546 B.C. , as Aristotle noted, there already existed a shrine dedicated to Theseus, but the exponential increase in artistic representations during Peisistratos’ reign through 527 B.C. displayed the growing importance of the hero to political agenda. Peisistratos took Theseus to be not only the national hero, but his own personal hero, and used the Cretan adventures to justify his links to the island sanctuary of Delos and his own reorganization of the festival of Apollo there. It was during this period that Theseus’s relevance as national hero started to overwhelm Herakles’ importance as Panhellenic hero, further strengthening Athenian civic pride.

Under Kleisthenes, the polis was reorganized into an even more inclusive democracy, by dividing the city into tribes, trittyes, and demes, a structure that may have been meant to reflect the organization of the Synoikismos. Kleisthenes also took a further step to outwardly claim Theseus as the Athenian hero by placing him in the metopes of the Athenian treasury at Delphi, where he could be seen by Greeks from every polis in the Aegean.

The oligarch Kimon (ca. 510–450 B.C. ) can be considered the ultimate patron of Theseus during the early to mid-fifth century B.C. After the first Persian invasion (ca. 490 B.C. ), Theseus came to symbolize the victorious and powerful city itself. At this time, the Amazonomachy became a key piece of iconography as the Amazons came to represent the Persians as eastern invaders. In 476 B.C. , Kimon returned Theseus’ bones to Athens and built a shrine around them which he had decorated with the Amazonomachy, the Centauromachy, and the Cretan adventures, all painted by either Mikon or Polygnotos, two of the most important painters of antiquity. This act represented the final solidification of Theseus as national hero.

Greene, Andrew. “Theseus, Hero of Athens.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/thes/hd_thes.htm (August 2009)

Further Reading

Barber, Elizabeth Wayland, and Paul T. Barber. When They Severed Earth from Sky: How the Human Mind Shapes Myth . Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Boardman, John "Herakles." In Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologicae Classicae , vol. V, 1. Zürich: Artemis, 1981.

Camp, John McK. The Archaeology of Athens . New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001.

Gehrke, Hans-Joachim. "Myth, History, and Collective Identity: Uses of the Past in Ancient Greece and Beyond." In The Historian's Craft in the Age of Herodotus , edited by Nino Luraghi, pp. 286–313. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Harrison, Evelyn B. "Motifs of the City Siege of Athena Parthenos." American Journal of Archaeology 85, no. 3 (July 1981), pp. 281–317.

Hornblower, Simon, and Antony Spawforth, eds. The Oxford Classical Dictionary . 3d ed., rev. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Neils, Jenifer. "Theseus." In Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologicae Classicae , vol. VII, 1, pp. 922–51. Zürich: Artemis, 1981.

Servadei, Cristina. La figura di Theseus nella ceramica attica: Iconografia e iconologia del mito nell'Atene arcaica e classica . Bologna: Ante Quem, 2005.

Shapiro, H. A. "Theseus: Aspects of the Hero in Archaic Greece." In New Perspectives in Early Greek Art , edited by Diana Buitron-Oliver, pp. 123–40. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1991.

Shapiro, H. A. Art and Cult under the Tyrants in Athens . Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern, 1989.

Simon, Erika. Festivals of Attica . Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1983.

Related Essays

- Greek Gods and Religious Practices

- The Labors of Herakles

- Minoan Crete

- The Achaemenid Persian Empire (550–330 B.C.)

- Ancient Greek Colonization and Trade and their Influence on Greek Art

- Athenian Vase Painting: Black- and Red-Figure Techniques

- Death, Burial, and the Afterlife in Ancient Greece

- Greek Art in the Archaic Period

- Heroes in Italian Mythological Prints

- The Kithara in Ancient Greece

- Music in Ancient Greece

- Mycenaean Civilization

- Mystery Cults in the Greek and Roman World

- Paintings of Love and Marriage in the Italian Renaissance

- The Rediscovery of Classical Antiquity

- Scenes of Everyday Life in Ancient Greece

- Women in Classical Greece

List of Rulers

- List of Rulers of the Ancient Greek World

- Ancient Greece, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- Ancient Greece, 1–500 A.D.

- Achaemenid Empire

- Ancient Greek Art

- Ancient Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Roman Art

- Anthropomorphism

- Archaeology

- Archaic Period

- Black-Figure Pottery

- Classical Period

- Deity / Religious Figure

- Funerary Art

- Greek and Roman Mythology

- Greek Literature / Poetry

- Herakles / Hercules

- Homer’s Iliad

- Homer’s Odyssey

- Literature / Poetry

- Mycenaean Art

- Mythical Creature

- Painted Object

- Poseidon / Neptune

- Relief Sculpture

- Sarcophagus

- Sculpture in the Round

Artist or Maker

- Briseis Painter

- Diosphos Painter

- Dwarf Painter

- Eretria Painter

- Pollaiuolo, Antonio

- Polygnotos Group

- Taleides Painter

ARTS & CULTURE

An absolutely fabulous celebration of history’s greatest divas.

This heady, exquisitely delightful new book reveals the power behind the sequins

Brandon Tensley

:focal(800x503:801x504)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d0/84/d0840f93-a9cf-4471-998b-094a82ea3791/jun24diva.jpg)

Bottled rage, sublime violence, threats and tears, love and anger. Never has a woman bared so much of her soul,” the French dramatist and poet Théophile Gautier wrote of Italian opera singer Giulia Grisi in the 1830s. Gautier was the first to use “diva”—Latin for “goddess”—to describe an opera soloist of epic talent. In the next two centuries, the term moved from describing performers—Bette Davis, Eartha Kitt, Diana Ross, Beyoncé—to describing almost anyone who’s fierce, provocative and generally beaucoup.

In her latest book, American Diva: Extraordinary, Unruly, Fabulous , Deborah Paredez, who teaches creative writing at Columbia University, celebrates divas of all sorts, arguing that their successes are particularly inspiring for people in marginalized communities, especially racial minorities. Paredez weaves historical accounts of these bold women into a thrilling cultural memoir: Over 250-odd pages, she illustrates how divas have historically used their authoritative talents to embolden the lives of those on society’s fringes.

Take Rita Moreno, the Puerto Rican actress who stunned viewers with her portrayal of Anita in the 1961 film adaptation of West Side Story . Paredez describes how, for many Latinos, Moreno’s turn as the heroine Anita, with her high kicks and twirls, challenged inherited notions of who could make claims to own a spot in America—at a time when film and theater were both still lily-white. “She moves across dance styles and harmonies and perspectives and the borderlines of turf and tribe,” Paredez writes of Moreno’s rebellious spirit. In similar ways, Tina Turner and Aretha Franklin assumed a diva persona that electrified their Black fans while creating opportunities for later Black artists who also wanted to make a living in the white worlds of rock and pop.

Most people associate the “diva” title with singers, such as Judy Garland and Whitney Houston, who are tagged as being high maintenance, or merely too much . Paredez reclaims the “diva” label as a celebration—and makes an intriguing case for widening the canon to include Venus and Serena Williams, “shimmering divas” who “were neither queens nor princesses, though they held countless titles” and became something like tennis royalty.

By the book’s end, Paredez’s thesis becomes entirely persuasive: The word “diva” is best used not for an opera virtuoso, but for any bold person whose work nourishes people too often starved of power.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/48/13/4813a69c-cc37-4e04-a104-2c68a5072d9a/microsoftteams-image.png)

Subscribe to Smithsonian magazine now for just $19.99

This article is a selection from the June 2024 issue of Smithsonian magazine

Get the latest Travel & Culture stories in your inbox.

Brandon Tensley | READ MORE

Brandon Tensley is a national political writer at CNN, where he covers culture and politics. His work has appeared in The Atlantic , Time and the Washington Post .

Advertisement

Supported by

‘Tits Up’ Aims to Show Breasts a Respect Long Overdue

The sociologist Sarah Thornton visits strip clubs, milk banks and cosmetic surgeons with the goal of shoring up appreciation for women’s breasts.

- Share full article

By Lucinda Rosenfeld

Lucinda Rosenfeld, a novelist and essayist, is the author of five books, including “Class.”

- Barnes and Noble

- Books-A-Million

When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission.

TITS UP: What Sex Workers, Milk Bankers, Plastic Surgeons, Bra Designers, and Witches Tell Us About Breasts, by Sarah Thornton

It’s a testament to the sociologist Sarah Thornton’s central thesis — women’s breasts are unjustly sexualized, trivialized and condescended to — that I expected her new book, “Tits Up,” to be a light read. In fact, her impassioned polemic makes a convincing case that the derogatory way Western culture views tits (Thornton contrasts her chosen slang with the relatively “silly” and “foolish” boobs ) helps perpetuate the patriarchy.

Breasts have been seen as “visible obstacles to equality, associated with nature and nurture rather than reason and power,” Thornton announces upfront. Over five, sometimes fascinating, sometimes frustrating chapters, each examining mammaries in a different context, “Tits Up” asks readers to reimagine the bosom, no matter its size and shape, as a site of empowerment and even divinity.

The author of a similarly discursive survey of the early 2000s art world , Thornton arrived at her new topic not entirely by choice. In 2018, after one too many stressful biopsies, she underwent a double mastectomy. But neither a fraught origin story nor Thornton’s argument that women are unfairly restrained by their mammalian status prevents “Tits Up” from being funny, too. Keen to make peace with her larger than expected implants — Thornton had requested more modest “lesbian yoga boobs” — she names her new pair Ernie and Bert.

The three of them soon hit the research road.

First stop: the Condor, a historic strip club in San Francisco, where Thornton interviews a racially and size-diverse group of strippers, who paint a relatively sunny portrait of a notoriously sleazy industry. Additional interviews with feminist sex activists and performance artists such as Annie Sprinkle — if you’re in need of a good laugh, Google “ Bosom Ballet ” — lead Thornton to conclude that, even when breasts are targets of overt objectification (after all, most patrons of topless bars are male), they might be thought of less as “sex toys” than as “salaried assistants.”

Feminists have been fighting about what’s now known as “sex work” for as long as feminism has been around. Thornton comes down squarely on the side of the workers. But she goes further than that. “I think the most fundamental issue inhibiting women’s autonomy — our right to choose what we do with our bodies — is the state’s policing of sex work,” she writes. “If some women can’t sell their bodies, then none of us actually own our bodies.” Reading these lines, I admit my first thought was, Huh? Should women’s ability to prostitute themselves really be the measure of our liberation?

But the chapter that follows, a cri de coeur on behalf of breastfeeding and the legacy of communal “allomothers” — women who nurse children who are not their own — seems to make a counterargument in favor of configuring breasts outside both capitalism and sexuality. After interviewing the women who run, provide and reap the benefits of a San Jose-based nonprofit milk “reservoir” (Thornton prefers the term to “bank”), she writes, “In a capitalist society where women’s breasts are commodified like no other body part, here their jugs are the key players in an economy that is not about money.”

It’s to Thornton’s credit that, her polemical tone notwithstanding, she is open-minded enough to entertain paradoxes. (And entertain she does.) While she despairs at the discouraging lingo that surrounds nursing — “milk letdown” comes in for particular condemnation — she admits to having felt conflicted while breastfeeding her own, now grown, children, insofar as the practice evoked for her the enervating specter of the selfless mother.

Semantics are at the heart of “Tits Up,” as Thornton rightly notes that the words we use inform the ideologies we subscribe to. But, again, the contradictions mount. Even as Thornton employs trans-activist-approved jargon such as “AMAB,” for assigned male at birth, and insists that both men and women have breasts, she draws the line at the term “chest feeding,” pointing out that “the expression obfuscates the highly gendered history of this maternal labor.”

Is it highly gendered or highly sexed? Either women’s lives are too much hampered by the fetishization and fear of their anatomy, or — paging Judith Butler — sexual difference is socially constructed and therefore, at least in theory, susceptible to change. I don’t quite see how these arguments can coexist.

Another research trip lands Thornton in the studio of a mass-market bra designer, where she decides that, although the brassiere is an impressive feat of engineering designed to make women feel safe, it’s past time we stopped hiding our nipples. In the operating room of a high-end plastic surgeon who performs augmentations, lifts and reductions, she concludes that breast alterations are not simply capitulations to normative beauty standards. Instead, such procedures might be understood in terms of female agency — as gestures that exist outside the logic of resistance or submission. Finally, she attends a neo-pagan retreat for women in the California redwoods, where she reflects on how alternative spiritual practices provide more space for aging female bodies — the kind of woman once referred to as a “crone” — and fantasizes half in jest about a world where saggy breasts are regarded as “sagacious.”

Drawing on her art history background, Thornton also leads us on an enlightening tour of female deities and their bosoms, including the Greek goddess of the hunt, Artemis (frequently depicted with multiple breasts); a Buddhist goddess of compassion, Guanyin (always portrayed as pancake flat); and the Virgin Mary, who, in portraits of her nursing baby Jesus, often appears to have only one boob. (Go figure.)

What does it all add up to? “Women have no federal right to breastfeed or to obtain an abortion, but we have the right to fake tits,” Thornton writes, noting that since 1998 health insurance companies have been required to pay for breast implants following medically necessary mastectomies. But what would a “federal right to breastfeed” look like, anyway? This declaration is among countless thought-provoking ones in this deceptively trenchant if inconsistently argued treatise. In any event, I eagerly await the sequel: “Asses Down”?

TITS UP : What Sex Workers, Milk Bankers, Plastic Surgeons, Bra Designers, and Witches Tell Us About Breasts | By Sarah Thornton | Norton | 307 pp. | $28.99

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

As book bans have surged in Florida, the novelist Lauren Groff has opened a bookstore called The Lynx, a hub for author readings, book club gatherings and workshops , where banned titles are prominently displayed.

Eighteen books were recognized as winners or finalists for the Pulitzer Prize, in the categories of history, memoir, poetry, general nonfiction, fiction and biography, which had two winners. Here’s a full list of the winners .

Montreal is a city as appealing for its beauty as for its shadows. Here, t he novelist Mona Awad recommends books that are “both dreamy and uncompromising.”

The complicated, generous life of Paul Auster, who died on April 30 , yielded a body of work of staggering scope and variety .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Thesis was the primordial, ancient Greek goddess of creation, a divinity related to Physis (Mother Nature). She occurs in the Orphic Theogonies as the first being to emerge at creation alongside Hydros (the Primordial Waters) and Mud. Thesis was sometimes portrayed as the female aspect of the first-born, bi-gendered god Phanes (Life).

Thetis (/ ˈ θ iː t ɪ s / THEEH-tiss, / ˈ θ ɛ t ɪ s / THEH-tiss; Greek: Θέτις) is a figure from Greek mythology with varying mythological roles. She mainly appears as a sea nymph, a goddess of water, and one of the 50 Nereids, daughters of the ancient sea god Nereus.. When described as a Nereid in Classical myths, Thetis was the daughter of Nereus and Doris, and a granddaughter of ...

The name Thesis is one given to a rarely spoken about goddess from Greek mythology; with her name mainly surviving only in fragments of ancient texts. In her own right Thesis was an important goddess for she was a Greek goddess of Creation, but Thesis' role was within the Orphic tradition whilst surviving tales are based on the tradition ...

Avi Kapach is a writer, scholar, and educator who received his PhD in Classics from Brown University. Thetis was a nymph and goddess of the sea, one of the fifty Nereids born to Nereus and Doris, and the wife of the mortal hero Peleus. When her son Achilles went to fight in the Trojan War, she did everything in her power to prevent his death.

Thetis Facts Summarized. Thetis is a daughter of Nereus, making her a Nereid, and is often associated with the sea's gentle and protective qualities. A prophecy stated that Thetis's son would be greater than his father, leading to her marriage with the mortal Peleus and the birth of Achilles. Beyond her maternal role, Thetis is known for ...

Greek Gods and Goddesses - Thetis (May 02, 2024) "Peleus Taming Thetis," pelike by the Marsyas Painter, c. 340-330 bc; in the British Museum. Thetis, in Greek mythology, a Nereid loved by Zeus and Poseidon. When Themis (goddess of Justice), however, revealed that Thetis was destined to bear a son who would be mightier than his father, the ...

Thetis was an ancient goddess of the sea and the leader of the fifty Nereides. Like many other sea gods she possessed the gift of prophesy and power to change her shape at will. Because of a prophesy that she was destined to bear a son greater than his father, Zeus had her marry a mortal man. Peleus, the chosen groom, was instructed to ambush her on the beach, and not release his grasp of the ...

In Greek mythology, Thesis is the primordial goddess of creation, often associated with the concept of Physis (Mother Nature).She is believed to have emerged at the beginning of creation alongside Hydros (the Primordial Waters) and Mud.Thesis is sometimes portrayed as the female aspect of the first-born deity, Phanes. She holds a significant role in ancient cosmology and mythology's origins.

Hesiod's primordial genealogy. Hesiod's Theogony, (c. 700 BCE) which could be considered the "standard" creation myth of Greek mythology, tells the story of the genesis of the gods. After invoking the Muses (II.1-116), Hesiod says the world began with the spontaneous generation of four beings: first arose Chaos (Chasm); then came Gaia (the Earth), "the ever-sure foundation of all"; "dim ...

Thetis and Zeus. Thetis was the second goddess to be rejected by Zeus because he feared the power of her son. She didn't give birth to a god, though; Thetis was the mother of a glorious hero! Thetis was not one of the major goddesses of the Greek pantheon. Considering her status, her impact on mythology was oversized.

Thetis was a sea goddess of ancient Greek mythology and leader of the Nereides, a group of fifty nymphs that represented the many characteristics of the seas. She played a strong supporting role ...

Thesis. is a primordial goddess of creation in ancient Greek religion. She is sometimes thought to be the child of Khaos, and emerged with Hydros. It is believed that she and her sibling created the world Gaia and the waters that surround her, or either that cooperated with Khaos in the process.

Thesis (goddess) Thesis ( Greek Θέσις; Thesis) is a primordial goddess of creation in ancient Greek religion. [1] She is sometimes thought to be the child of Chaos, and emerged with Hydros. It is believed that she and her sibling created the world Gaia and the waters that surround her, or either that cooperated with Chaos in the process.

In the annals of Greek mythology, Thesis's influence extends far beyond the realm of celestial mechanics, permeating various aspects of human civilization, from the realms of art and literature to the spheres of governance and jurisprudence. His essence embodies the inherent desire for structure and coherence that lies at the heart of human ...

Theseus (UK: / ˈ θ iː sj uː s /, US: / ˈ θ iː s i ə s /; Greek: Θησεύς [tʰɛːsěu̯s]) was a divine hero and the founder of Athens from Greek mythology.The myths surrounding Theseus, his journeys, exploits, and friends, have provided material for storytelling throughout the ages. Theseus is sometimes described as the son of Aegeus, King of Athens, and sometimes as the son of ...

In Greek mythology was the god of the primordial waters. In the Orphic Theogonies Hydros (Water), Thesis (Creation) and Mud were the first entities to emerge at the dawn of creation. Mud in turn solidified into Gaea (Earth) who, together with Hydros, produced Chronos (Time) and Ananke (Compulsion). This latter pair then crushed the cosmic-egg with their serpentine coils to hatch Phanes (Life ...

Theseus' life can be divided into two distinct periods, as a youth and as king of Athens. Aegeus, king of Athens, and the sea god Poseidon ( 53.11.4) both slept with Theseus' mother, Aithra, on the same night, supplying Theseus with both divine and royal lineage. Theseus was born in Aithra's home city of Troezen, located in the ...

Themis, in Greek religion, personification of justice, goddess of wisdom and good counsel, and the interpreter of the gods' will.According to Hesiod's Theogony, she was the daughter of Uranus (Heaven) and Gaea (Earth), although at times she was apparently identified with Gaea, as in Aeschylus's Eumenides and Prometheus Bound.In Hesiod she is Zeus's second consort and by him the mother ...

Myths / Heroes / Theseus. The son of either Poseidon or Aegeus and Aethra, Theseus was widely considered the greatest Athenian hero, the king who managed to politically unify Attica under the aegis of Athens. Son of either Aegeus, the king of Athens, or Poseidon, the god of the sea, and Aethra, a princess, Theseus was raised by his mother in ...

The voices of these women from. Greek myth, when brought together, then resemble more of a chorus, and their stories become a. loud and clear call for change that is needed in the actions and minds of society in order to create. a safer and equal space for women to not only exist, but freely express themselves.

Physis is a goddess who appears primarily in the Orphic tradition of Greek mythology. In the Orphic tradition, Physis is the goddess of nature, both the origin of nature, and the natural order of things. ... From her though, all of nature derived, and so Physis can be thought of similarly to Eros, Phanes and Thesis. The English word Physics ...

Mythology Redefined: A Creative Thesis By Tracy Carlin A departmental senior thesis submitted to the Department of English at Trinity University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with departmental honors. DATE April 20th, 2010 _____ _____ THESIS ADVISOR DEPARTMENT CHAIR

Translation. Origin, Nature ( phusis) PHYSIS was the primordial goddess of the origin and ordering of nature. The Orphics titled her Protogeneia "the First Born." Physis was similar to the primordial deities Eros (Procreation), Phanes and Thesis (Creation). The creator-god was regarded as both male and female.

Gautier was the first to use "diva"—Latin for "goddess"—to describe an opera soloist of epic talent. ... By the book's end, Paredez's thesis becomes entirely persuasive: The word ...

Drawing on her art history background, Thornton also leads us on an enlightening tour of female deities and their bosoms, including the Greek goddess of the hunt, Artemis (frequently depicted with ...

HWST 270, Hawaiian Mythology [ F17, F15 ] HWST 275, Wahi Pana [ F18, S16 ] HWST 296, Nā Mo'olelo o Ko'olau [ SUM 18 ] Graduate Teaching Assistant, Fall 2015 - Fall 2016 Hawai`inuiakea School of Hawaiian Knowledge Fall 2009 - Spring 2010 HWST 107, Hawai'i: Center of the Pacific [F17, S17, F16, S16, F15, S15]