Broken Windows Theory of Criminology

Charlotte Ruhl

Research Assistant & Psychology Graduate

BA (Hons) Psychology, Harvard University

Charlotte Ruhl, a psychology graduate from Harvard College, boasts over six years of research experience in clinical and social psychology. During her tenure at Harvard, she contributed to the Decision Science Lab, administering numerous studies in behavioral economics and social psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

The Broken Windows Theory of Criminology suggests that visible signs of disorder and neglect, such as broken windows or graffiti, can encourage further crime and anti-social behavior in an area, as they signal a lack of order and law enforcement.

Key Takeaways

- The Broken Windows theory, first studied by Philip Zimbardo and introduced by George Kelling and James Wilson, holds that visible indicators of disorder, such as vandalism, loitering, and broken windows, invite criminal activity and should be prosecuted.

- This form of policing has been tested in several real-world settings. It was heavily enforced in the mid-1990s under New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani, and Albuquerque, New Mexico, Lowell, Massachusetts, and the Netherlands later experimented with this theory.

- Although initial research proved to be promising, this theory has been met with several criticisms. Specifically, many scholars point to the fact that there is no clear causal relationship between lack of order and crime. Rather, crime going down when order goes up is merely a coincidental correlation.

- Additionally, this theory has opened the doors for racial and class bias, especially in the form of stop and frisk.

The United States has the largest prison population in the world and the highest per-capita incarceration rate. In 2016, 2.3 million people were incarcerated, despite a massive decline in both violent and property crimes (Morgan & Kena, 2019).

These statistics provide some insight into why crime regulation and mass incarceration are such hot topics today, and many scholars, lawyers, and politicians have devised theories and strategies to try to promote safety within society.

One such model is broken windows policing, which was first brought to light by American psychologist Philip Zimbardo (famous for his Stanford Prison Experiment) and further publicized by James Wilson and George Kelling. Since its inception, this theory has been both widely used and widely criticized.

What Is the Broken Windows Theory?

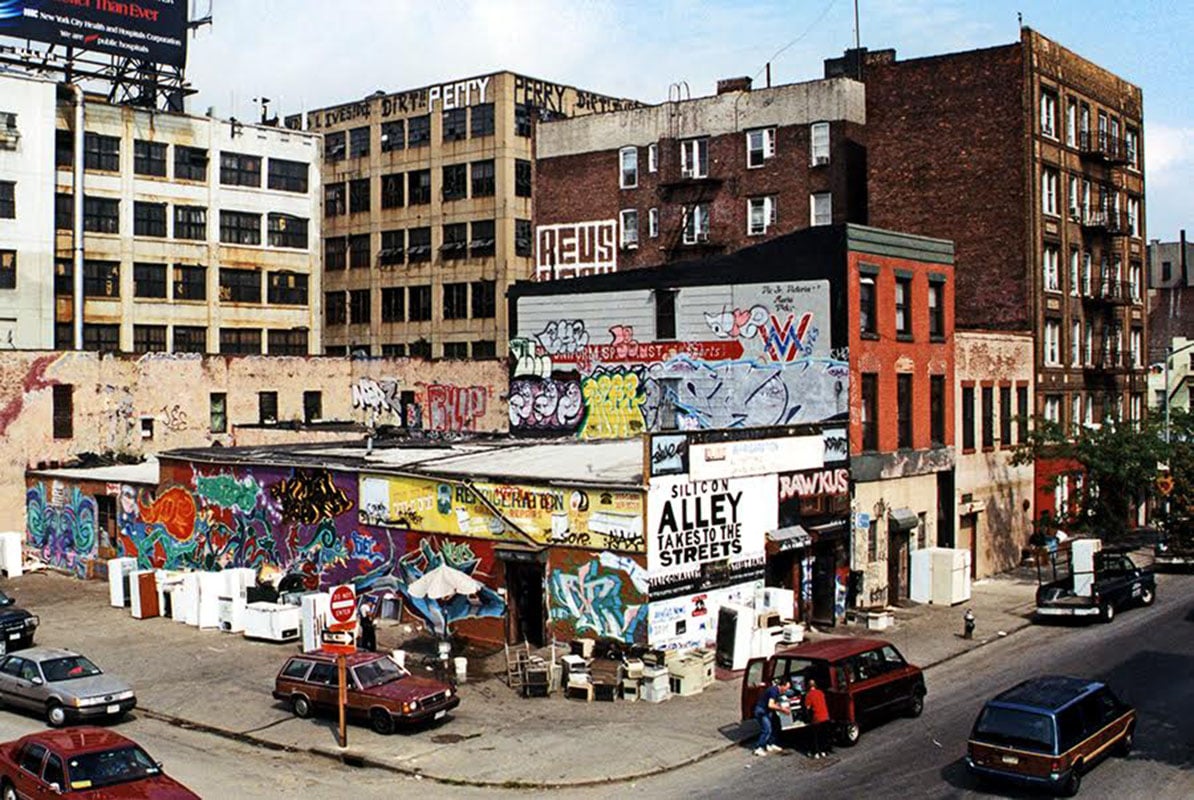

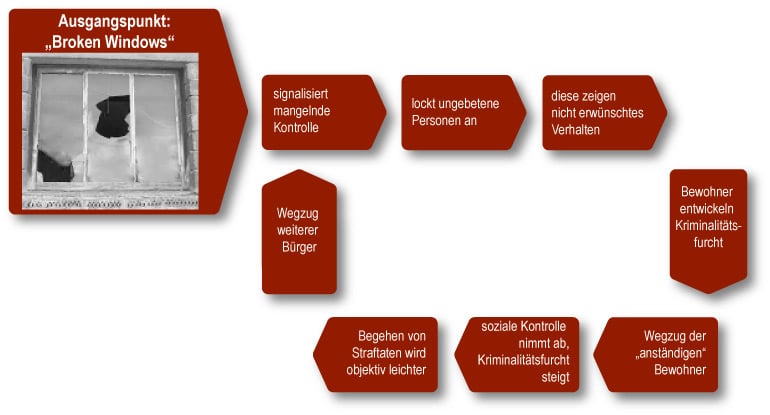

The broken windows theory states that any visible signs of crime and civil disorder, such as broken windows (hence, the name of the theory), vandalism, loitering, public drinking, jaywalking, and transportation fare evasion, create an urban environment that promotes even more crime and disorder (Wilson & Kelling, 1982).

As such, policing these misdemeanors will help create an ordered and lawful society in which all citizens feel safe and crime rates, including violent crime rates, are low.

Broken windows policing tries to regulate low-level crime to prevent widespread disorder from occurring. If these small crimes are greatly reduced, then neighborhoods will appear to be more cared for.

The hope is that if these visible displays of disorder and neglect are reduced, violent crimes might go down too, leading to an overall reduction in crime and an increase in public safety.

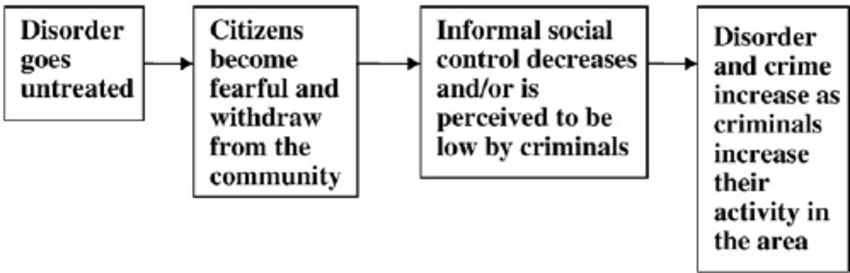

Source: Hinkle, J. C., & Weisburd, D. (2008). The irony of broken windows policing: A micro-place study of the relationship between disorder, focused police crackdowns and fear of crime. Journal of Criminal Justice, 36(6), 503-512.

Academics justify broken windows policing from a theoretical standpoint because of three specific factors that help explain why the state of the urban environment might affect crime levels:

- social norms and conformity;

- the presence or lack of routine monitoring;

- social signaling and signal crime.

In a typical urban environment, social norms and monitoring are not clearly known. As a result, individuals will look for certain signs and signals that provide both insight into the social norms of the area as well as the risk of getting caught violating those norms.

Those who support the broken windows theory argue that one of those signals is the area’s general appearance. In other words, an ordered environment, one that is safe and has very little lawlessness, sends the message that this neighborhood is routinely monitored and criminal acts are not tolerated.

On the other hand, a disordered environment, one that is not as safe and contains visible acts of lawlessness (such as broken windows, graffiti, and litter), sends the message that this neighborhood is not routinely monitored and individuals would be much more likely to get away with committing a crime.

With a decreased likelihood of detection, individuals would be much more inclined to engage in criminal behavior, both violent and nonviolent, in this type of area.

As you might be able to tell, a major assumption that this theory makes is that an environment’s landscape communicates to its residents in some way.

For example, proponents of this theory would argue that a broken window signals to potential criminals that a community is unable to defend itself against an uptick in criminal activity. It is not the literal broken window that is a direct cause for concern, but more so the figurative meaning that is ascribed to this situation.

It symbolizes a vulnerable and disjointed community that cannot handle crime – opening the doors to all kinds of unwanted activity to occur.

In neighborhoods that do have a strong sense of social cohesion among their residents, these broken windows are fixed (both literally and figuratively), giving these areas a sense of control over their communities.

By fixing these windows, undesired individuals and behaviors are removed, allowing civilians to feel safer (Herbert & Brown, 2006).

However, in environments in which these broken windows are left unfixed, residents no longer see their communities as tight-knit, safe spaces and will avoid spending time in communal spaces (in parks, at local stores, on the street blocks) so as to avoid violent attacks from strangers.

Additionally, when these broken windows are not fixed, it also symbolizes a lack of informal social control. Informal social control refers to the actions that regulate behavior, such as conforming to social norms and intervening as a bystander when a crime is committed, that are independent of the law.

Informal social control is important to help reduce unruly behavior. Scholars argue that, under certain circumstances, informal social control is more effective than laws.

And some will even go so far as to say that nonresidential spaces, such as corner stores and businesses, have a responsibility to actually maintain this informal social control by way of constant surveillance and supervision.

One such scholar is Jane Jacobs, a Canadian-American author and journalist who believed sidewalks were a crucial vehicle for promoting public safety.

Jacobs can be considered one of the original pioneers of the broken windows theory. One of her most famous books, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, describes how local businesses and stores provide a necessary sense of having “eyes on the street,” which promotes safety and helps to regulate crime (Jacobs, 1961).

Although the idea that community involvement, from both residents and non-residents, can make a big difference in how safe a neighborhood is perceived to be, Wilson and Keeling argue that the police are the key to maintaining order.

As major proponents of broken windows policing, they hold that formal social control, in addition to informal social control, is crucial for actually regulating crime.

Although different people have different approaches to the implementation of broken windows (i.e., cleaning up the environment and informal social control vs. an increase in policing misdemeanor crimes), the end goal is the same: crime reduction.

This idea, which largely serves as the backbone of the broken windows theory, was first introduced by Philip Zimbardo.

Examples of Broken Windows Policing

1969: philip zimbardo’s introduction of broken windows in nyc and la.

In 1969, Stanford psychologist Philip Zimbardo ran a social experiment in which he abandoned two cars that had no license plates and the hoods up in very different locations.

The first was a predominantly poor, high-crime neighborhood in the Bronx, and the second was a fairly affluent area of Palo Alto, California. He then observed two very different outcomes.

After just ten minutes, the car in the Bronx was attacked and vandalized. A family first approached the vehicle and removed the radiator and battery. Within the first twenty-four hours after Zimbardo left the car, everything valuable had been stripped and removed from the car.

Afterward, random acts of destruction began – the windows were smashed, seats were ripped up, and the car began to serve as a playground for children in the community.

On the contrary, the car that was left in Palo Alto remained untouched for more than a week before Zimbardo eventually went up to it and smashed the vehicle with a sledgehammer.

Only after he had done this did other people join the destruction of the car (Zimbardo, 1969). Zimbardo concluded that something that is clearly abandoned and neglected can become a target for vandalism.

But Kelling and Wilson extended this finding when they introduced the concept of broken windows policing in the early 1980s.

This initial study cascaded into a body of research and policy that demonstrated how in areas such as the Bronx, where theft, destruction, and abandonment are more common, vandalism would occur much faster because there are no opposing forces to this type of behavior.

As a result, such forces, primarily the police, are needed to intervene and reduce these types of behavior and remove such indicators of disorder.

1982: Kelling and Wilson’s Follow-Up Article

Thirteen years after Zimbardo’s study was published, criminologists George Kelling and James Wilson published an article in The Atlantic that applied Zimbardo’s findings to entire communities.

Kelling argues that Zimbardo’s findings were not unique to the Bronx and Palo Alto areas. Rather, he claims that, regardless of the neighborhood, a ripple effect can occur once disorder begins as things get extremely out of hand and control becomes increasingly hard to maintain.

The article introduces the broader idea that now lies at the heart of the broken windows theory: a broken window, or other signs of disorder, such as loitering, graffiti, litter, or drug use, can send the message that a neighborhood is uncared for, sending an open invitation for crime to continue to occur, even violent crimes.

The solution, according to Kelling and Wilson and many other proponents of this theory, is to target these very low-level crimes, restore order to the neighborhood, and prevent more violent crimes from happening.

A strengthened and ordered community is equipped to fight and deter crime (because a sense of order creates the perception that crimes go easily detected). As such, it is necessary for police departments to focus on cleaning up the streets as opposed to putting all of their energy into fighting high-level crimes.

In addition to Zimbardo’s 1969 study, Kelling and Wilson’s article was also largely inspired by New Jersey’s “Safe and Clean Neighborhoods Program” that was implemented in the mid-1970s.

As part of the program, police officers were taken out of their patrol cars and were asked to patrol on foot. The aim of this approach was to make citizens feel more secure in their neighborhoods.

Although crime was not reduced as a result, residents took fewer steps to protect themselves from crime (such as locking their doors). Reducing fear is a huge goal of broken-windows policing.

As Kelling and Wilson state in their article, the fear of being bothered by disorderly people (such as drunks, rowdy teens, or loiterers) is enough to motivate them to withdraw from the community.

But if we can find a way to make people feel less fear (namely by reducing low-level crimes), then they will be more involved in their communities, creating a higher degree of informal social control and deterring all forms of criminal activity.

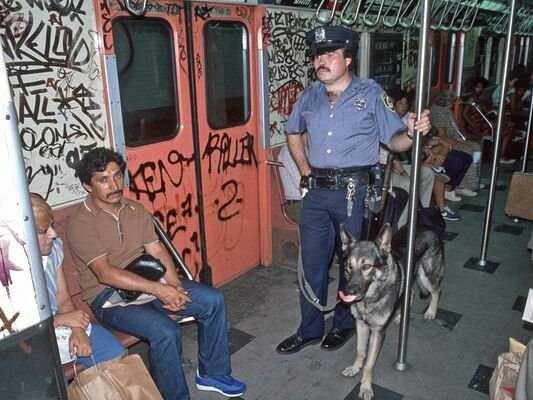

Although Kelling and Wilson’s article was largely theoretical, the practice of broken windows policing was implemented in the early 1990s under New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani. And Kelling himself was there to play a crucial role.

Early 1990s: Bratton and Giuliani’s implementation in NYC

In 1985, the New York City Transit Authority hired George Kelling as a consultant, and he was also later hired by both the Boston and Los Angeles police departments to provide advice on the most effective method for policing (Fagan & Davies, 2000).

Five years later, in 1990, William J. Bratton became the head of the New York City Transit Police. In his role, Bratton cracked down on fare evasion and implemented faster methods to process those who were arrested.

He attributed a lot of his decisions as head of the transit police to Kelling’s work. Bratton was just the first to begin to implement such measures, but once Rudy Giuliani was elected as mayor in 1993, tactics to reduce crime began to really take off (Vedantam et al., 2016).

Together, Giuliani and Bratton first focused on cleaning up the subway system, where Bratton’s area of expertise lay. They sent hundreds of police officers into subway stations throughout the city to catch anyone who was jumping the turnstiles and evading the fair.

And this was just the beginning.

All throughout the 90s, Giuliani increased misdemeanor arrests in all pockets of the city. They arrested numerous people for smoking marijuana in public, spraying graffiti on walls, selling cigarettes, and they shut down many of the city’s night spots for illegal dancing.

Conveniently, during this time, crime was also falling in the city and the murder rate was rapidly decreasing, earning Giuliani re-election in 1997 (Vedantam et al., 2016).

To further support the outpouring success of this new approach to regulating crime, George Kelling ran a follow-up study on the efficacy of broken windows policing and found that in neighborhoods where there was a stark increase in misdemeanor arrests (evidence of broken windows policing), there was also a sharp decline in crime (Kelling & Sousa, 2001).

Because this seemed like an incredibly successful mode, cities around the world began to adopt this approach.

Late 1990s: Albuquerque’s Safe Streets Program

In Albuquerque, New Mexico, a Safe Streets Program was implemented to deter and reduce unsafe driving and crime rates by increasing surveillance in these areas.

Specifically, the traffic enforcement program influenced saturation patrols (that operated over a large geographic area), sobriety checkpoints, follow-up patrols, and freeway speed enforcement.

The effectiveness of this program was analyzed in a study done by the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (Stuser, 2001).

Results demonstrated that both Part I crimes, including homicide, forcible rape, robbery, and theft, and Part II crimes, such as sex offenses, kidnapping, stolen property, and fraud, experienced a total decline of 5% during the 1996-1997 calendar year in which this program was implemented.

Additionally, this program resulted in a 9% decline in both robbery and burglary, a 10% decline in assault, a 17% decline in kidnapping, a 29% decline in homicide, and a 36% decline in arson.

With these promising statistics came a 14% increase in arrests. Thus, the researchers concluded that traffic enforcement programs can deter criminal activity. This approach was initially inspired by both Zimbardo’s and Kelling and Wilson’s work on broken windows and provides evidence that when policing and surveillance increase, crime rates go down.

2005: Lowell, Massachusetts

Back on the east coast, Harvard University and Suffolk University researchers worked with local police officers to pinpoint 34 different crime hotspots in Lowell, Massachusetts. In half of these areas, local police officers and authorities cleaned up trash from the streets, fixed streetlights, expanded aid for the homeless, and made more misdemeanor arrests.

There was no change made in the other half of the areas (Johnson, 2009).

The researchers found that in areas in which police service was changed, there was a 20% reduction in calls to the police. And because the researchers implemented different ways of changing the city’s landscape, from cleaning the physical environment to increasing arrests, they were able to compare the effectiveness of these various approaches.

Although many proponents of the broken windows theory argue that increasing policing and arrests is the solution to reducing crime, as the previous study in Albuquerque illustrates. Others insist that more arrests do not solve the problem but rather changing the physical landscape should be the desired means to an end.

And this is exactly what Brenda Bond of Suffolk University and Anthony Braga of Harvard Kennedy’s School of Government found. Cleaning up the physical environment was revealed to be very effective, misdemeanor arrests were less so, and increasing social services had no impact.

This study provided strong evidence for the effectiveness of the broken windows theory in reducing crime by decreasing disorder, specifically in the context of cleaning up the physical and visible neighborhood (Braga & Bond, 2008).

2007: Netherlands

The United States is not the only country that sought to implement the broken windows ideology. Beginning in 2007, researchers from the University of Groningen ran several studies that looked at whether existing visible disorder increased crimes such as theft and littering.

Similar to the Lowell experiment, where half of the areas were ordered and the other half disorders, Keizer and colleagues arranged several urban areas in two different ways at two different times. In one condition, the area was ordered, with an absence of graffiti and littering, but in the other condition, there was visible evidence for disorder.

The team found that in disorderly environments, people were much more likely to litter, take shortcuts through a fenced-off area, and take an envelope out of an open mailbox that was clearly labeled to contain five Euros (Keizer et al., 2008).

This study provides additional support for the effect perceived order can have on the likelihood of criminal activity. But this broken windows theory is not restricted to the criminal legal setting.

2008: Tokyo, Japan

The local government of Adachi Ward, Tokyo, which once had Tokyo’s highest crime rates, introduced the “Beautiful Windows Movement” in 2008 (Hino & Chronopoulos, 2021).

The intervention was twofold. The program, on one hand, drawing on the broken windows theory, promoted policing to prevent minor crimes and disorder. On the other hand, in partnership with citizen volunteers, the authorities launched a project to make Adachi Ward literally beautiful.

Following 11 years of implementation, the reduction in crime was undeniable. Felony had dropped from 122 in 2008 to 35 in 2019, burglary from 104 to 24, and bicycle theft from 93 to 45.

This Japanese case study seemed to further highlight the advantages associated with translating the broken widow theory into both aggressive policing and landscape altering.

Other Domains Relevant to Broken Windows

There are several other fields in which the broken windows theory is implicated. The first is real estate. Broken windows (and other similar signs of disorder) can indicate low real estate value, thus deterring investors (Hunt, 2015).

As such, some recommend that the real estate industry adopt the broken windows theory to increase value in an apartment, house, or even an entire neighborhood. They might increase in value by fixing windows and cleaning up the area (Harcourt & Ludwig, 2006).

Consequently, this might lead to gentrification – the process by which poorer urban landscapes are changed as wealthier individuals move in.

Although many would argue that this might help the economy and provide a safe area for people to live, this often displaces low-income families and prevents them from moving into areas they previously could not afford.

This is a very salient topic in the United States as many areas are becoming gentrified, and regardless of whether you support this process, it is important to understand how the real estate industry is directly connected to the broken windows theory.

Another area that broken windows are related to is education. Here, the broken windows theory is used to promote order in the classroom. In this setting, the students replace those who engage in criminal activity.

The idea is that students are signaled by disorder or others breaking classroom rules and take this as an open invitation to further contribute to the disorder.

As such, many schools rely on strict regulations such as punishing curse words and speaking out of turn, forcing strict dress and behavioral codes, and enforcing specific classroom etiquette.

Similar to the previous studies, from 2004 to 2006, Stephen Plank and colleagues conducted a study that measured the relationship between the physical appearance of mid-Atlantic schools and student behavior.

They determined that variables such as fear, social order, and informal social control were statistically significantly associated with the physical conditions of the school setting.

Thus, the researchers urged educators to tend to the school’s physical appearance to help promote a productive classroom environment in which students are less likely to propagate disordered behavior (Plank et al., 2009).

Despite there being a large body of research that seems to support the broken windows theory, this theory does not come without its stark criticisms, especially in the past few years.

Major Criticisms

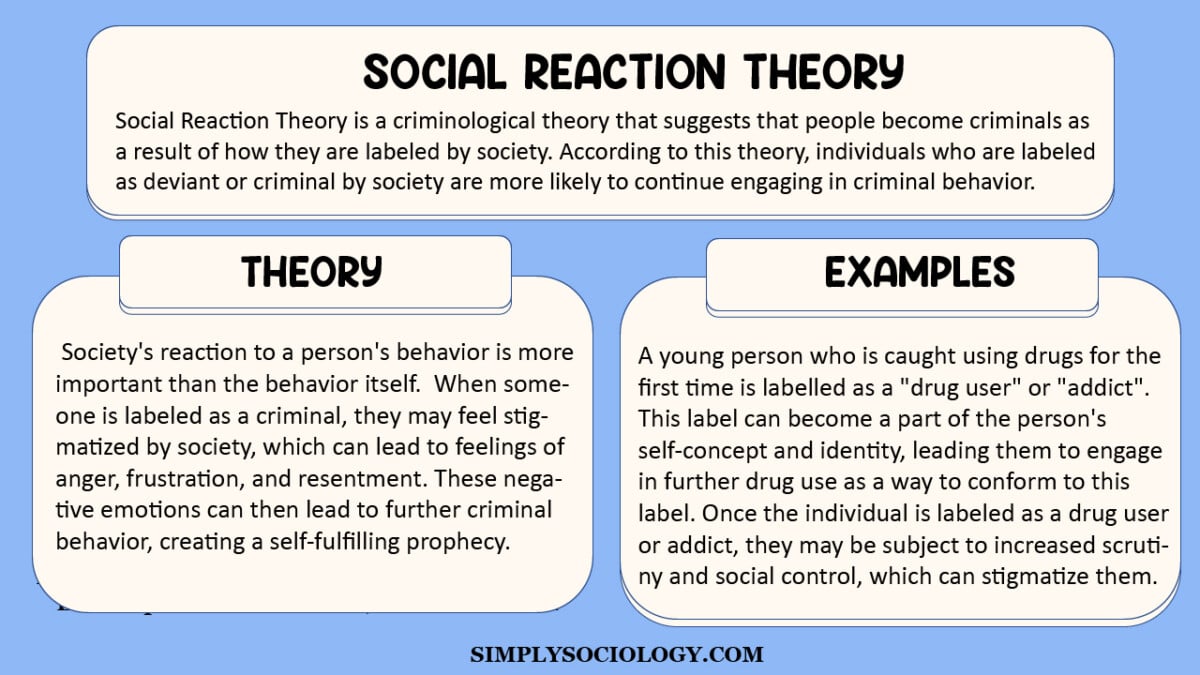

At the turn of the 21st century, the rhetoric surrounding broken windows drastically shifted from praise to criticism. Scholars scrutinized conclusions that were drawn, questioned empirical methodologies, and feared that this theory was morphing into a vehicle for discrimination.

Misinterpreting the Relationship Between Disorder and Crime

A major criticism of this theory argues that it misinterprets the relationship between disorder and crime by drawing a causal chain between the two.

Instead, some researchers argue that a third factor, collective efficacy, or the cohesion among residents combined with shared expectations for the social control of public space, is the causal agent explaining crime rates (Sampson & Raudenbush, 1999).

A 2019 meta-analysis that looked at 300 studies revealed that disorder in a neighborhood does not directly cause its residents to commit more crimes (O’Brien et al., 2019).

The researchers examined studies that tested to what extent disorder led people to commit crimes, made them feel more fearful of crime in their neighborhoods, and affected their perceptions of their neighborhoods.

In addition to drawing out several methodological flaws in the hundreds of studies that were included in the analysis, O’Brien and colleagues found no evidence that the disorder and crime are causally linked.

Similarly, in 2003, David Thatcher published a paper in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology arguing that broken windows policing was not as effective as it appeared to be on the surface.

Crime rates dropping in areas such as New York City were not a direct result of this new law enforcement tactic. Those who believed this were simply conflating correlation and causality.

Rather, Thatcher claims, lower crime rates were the result of various other factors, none of which fell into the category of ramping up misdemeanor arrests (Thatcher, 2003).

In terms of the specific factors that were actually playing a role in the decrease in crime, some scholars point to the waning of the cocaine epidemic and strict enforcement of the Rockefeller drug laws that contributed to lower crime rates (Metcalf, 2006).

Other explanations include trends such as New York City’s economic boom in the late 1990s that helped directly contribute to the decrease of crime much more so than enacting the broken windows policy (Sridhar, 2006).

Additionally, cities that did not implement broken windows also saw a decrease in crime (Harcourt, 2009), and similarly, crime rates weren’t decreasing in other cities that adopted the broken windows policy (Sridhar, 2006).

Specifically, Bernard Harcourt and Jens Ludwig examined the Department of Housing and Urban Development program that placed inner-city project residents into housing in more orderly neighborhoods.

Contrary to the broken windows theory, which would predict that these tenants would now commit fewer crimes once relocated into more ordered neighborhoods, they found that these individuals continued to commit crimes at the same rate.

This study provides clear evidence why broken windows may not be the causal agent in crime reduction (Harcourt & Ludwig, 2006).

Falsely Assuming Why Crimes Are Committed

The broken windows theory also assumes that in more orderly neighborhoods, there is more informal social control. As a result, people understand that there is a greater likelihood of being caught committing a crime, so they shy away from engaging in such activity.

However, people don’t only commit crimes because of the perceived likelihood of detection. Rather, many individuals who commit crimes do so because of factors unrelated to or without considering the repercussions.

Poverty, social pressure, mental illness, and more are often driving factors that help explain why a person might commit a crime, especially a misdemeanor such as theft or loitering.

Resulting in Racial and Class Bias

One of the leading criticisms of the broken windows theory is that it leads to both racial and class bias. By giving the police broad discretion to define disorder and determine who engages in disorderly acts allows them to freely criminalize communities of color and groups that are socioeconomically disadvantaged (Roberts, 1998).

For example, Sampson and Raudenbush found that in two neighborhoods with equal amounts of graffiti and litter, people saw more disorder in neighborhoods with more African Americans.

The researchers found that individuals associate African Americans and other minority groups with concepts of crime and disorder more so than their white counterparts (Sampson & Raudenbush, 2004).

This can lead to unfair policing in areas that are predominantly people of color. In addition, those who suffer from financial instability and may be of minority status are more likely to commit crimes in the first place.

Thus, they are simply being punished for being poor as opposed to being given resources to assist them. Further, many acts that are actually legal but are deemed disorderly by police officers are targeted in public settings but aren’t targeted when the same acts are conducted in private settings.

As a result, those who don’t have access to private spaces, such as homeless people, are unnecessarily criminalized.

It follows then that by policing these small misdemeanors, or oftentimes actions that aren’t even crimes at all, police departments are fighting poverty crimes as opposed to fighting to provide individuals with the resources that will make crime no longer a necessity.

Morphing into Stop and Frisk

Stop and frisk, a brief non-intrusive police stop of a suspect is an extremely controversial approach to policing. But critics of the broken windows theory argue that it has morphed into this program.

With broken-windows policing, officers have too much discretion when determining who is engaging in criminal activity and will search people for drugs and weapons without probable cause.

However, this method is highly unsuccessful. In 2008, the police made nearly 250,000 stops in New York, but only one-fifteenth of one percent of those stops resulted in finding a gun (Vedantam et al., 2016).

And three years later, in 2011, more than 685,000 people were stopped in New York. Of those, nine out of ten were found to be completely innocent (Dunn & Shames, 2020).

Thus, not only does this give officers free reins to stop and frisk minority populations at disproportionately high levels, but it also is not effective in drawing out crime.

Although broken windows policing might seem effective from a theoretical perspective, major valid criticisms put the practical application of this theory into question.

Given its controversial nature, broken windows policing is not explicitly used today to regulate crime in most major cities. However, there are still traces of this theory that remain.

Cities such as Ferguson, Missouri, are heavily policed and the city issues thousands of warrants a year on broken window types of crimes – from parking infractions to traffic violations.

And the racial and class biases that result from such an approach to law enforcement have definitely not disappeared.

Crime regulation is not easy, but the broken windows theory provides an approach to reducing offenses and maintaining order in society.

What is the broken glass principle?

The broken glass principle, also known as the Broken Windows Theory, posits that visible signs of disorder, like broken glass, can foster further crime and anti-social behavior by signaling a lack of regulation and community care in an area.

How does social context affect crime according to the broken windows theory?

The Broken Windows Theory proposes that the social context, specifically visible signs of disorder like vandalism or littering, can encourage further crime.

It suggests that these signs indicate a lack of community control and care, which can foster a climate of disregard for laws and social norms, leading to more severe crimes over time.

How did broken windows theory change policing?

The Broken Windows Theory influenced policing by promoting proactive attention to minor crimes and maintaining urban environments.

It led to strategies like “zero-tolerance” or “quality-of-life” policing, focusing on reducing visible signs of disorder to prevent more serious crime.

Braga, A. A., & Bond, B. J. (2008). Policing crime and disorder hot spots: A randomized controlled trial. Criminology, 46(3), 577-607.

Dunn, C., & Shames, M. (2020). Stop-and-Frisk data . Retrieved from https://www.nyclu.org/en/stop-and-frisk-data

Fagan, J., & Davies, G. (2000). Street stops and broken windows: Terry, race, and disorder in New York City. Fordham Urb. LJ , 28, 457.

Harcourt, B. E. (2009). Illusion of order: The false promise of broken windows policing . Harvard University Press.

Harcourt, B. E., & Ludwig, J. (2006). Broken windows: New evidence from New York City and a five-city social experiment. U. Chi. L. Rev., 73 , 271.

Herbert, S., & Brown, E. (2006). Conceptions of space and crime in the punitive neoliberal city. Antipode, 38 (4), 755-777.

Hunt, B. (2015). “Broken Windows” theory can be applied to real estate regulation- Realty Times. Retrieved from https://realtytimes.com/agentnews/agentadvice/item/40700-20151208-broken-windws-theory-can-be-applied-to-real-estate-regulation

Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities . Vintage.

Johnson, C. Y. (2009). Breakthrough on “broken windows.” Boston Globe.

Keizer, K., Lindenberg, S., & Steg, L. (2008). The spreading of disorder. Science, 322 (5908), 1681-1685.

Kelling, G. L., & Sousa, W. H. (2001). Do police matter?: An analysis of the impact of new york city’s police reforms . CCI Center for Civic Innovation at the Manhattan Institute.

Metcalf, S. (2006). Rudy Giuliani, American president? Retrieved from https://slate.com/culture/2006/05/rudy-giuliani-american-president.html

Morgan, R. E., & Kena, G. (2019). Criminal victimization, 2018. Bureau of Justice Statistics , 253043.

O”Brien, D. T., Farrell, C., & Welsh, B. C. (2019). Looking through broken windows: The impact of neighborhood disorder on aggression and fear of crime is an artifact of research design. Annual Review of Criminology, 2 , 53-71.

Plank, S. B., Bradshaw, C. P., & Young, H. (2009). An application of “broken-windows” and related theories to the study of disorder, fear, and collective efficacy in schools. American Journal of Education, 115 (2), 227-247.

Roberts, D. E. (1998). Race, vagueness, and the social meaning of order-maintenance policing. J. Crim. L. & Criminology, 89 , 775.

Sampson, R. J., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1999). Systematic social observation of public spaces: A new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. American Journal of Sociology, 105 (3), 603-651.

Sampson, R. J., & Raudenbush, S. W. (2004). Seeing disorder: Neighborhood stigma and the social construction of “broken windows”. Social psychology quarterly, 67 (4), 319-342.

Sridhar, C. R. (2006). Broken windows and zero tolerance: Policing urban crimes. Economic and Political Weekly , 1841-1843.

Stuster, J. (2001). Albuquerque police department’s Safe Streets program (No. DOT-HS-809-278). Anacapa Sciences, inc.

Thacher, D. (2003). Order maintenance reconsidered: Moving beyond strong causal reasoning. J. Crim. L. & Criminology, 94 , 381.

Vedantam, S., Benderev, C., Boyle, T., Klahr, R., Penman, M., & Schmidt, J. (2016). How a theory of crime and policing was born, and went terribly wrong . Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2016/11/01/500104506/broken-windows-policing-and-the-origins-of-stop-and-frisk-and-how-it-went-wrong

Wilson, J. Q., & Kelling, G. L. (1982). Broken windows. Atlantic monthly, 249 (3), 29-38.

Zimbardo, P. G. (1969). The human choice: Individuation, reason, and order versus deindividuation, impulse, and chaos. In Nebraska symposium on motivation. University of Nebraska press.

Further Information

- Wilson, J. Q., & Kelling, G. L. (1982). Broken windows. Atlantic monthly, 249(3), 29-38.

- Fagan, J., & Davies, G. (2000). Street stops and broken windows: Terry, race, and disorder in New York City. Fordham Urb. LJ, 28, 457.

- Fagan, J. A., Geller, A., Davies, G., & West, V. (2010). Street stops and broken windows revisited. In Race, ethnicity, and policing (pp. 309-348). New York University Press.

Related Articles

Criminology

What Do Criminal Psychologists Do?

Self-Control Theory Of Crime

Social Reaction Theory (Criminology)

What Is Social Control In Sociology?

Subcultural Theories of Deviance

Tertiary Deviance: Definition & Examples

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

- Amazon Alexa

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

How A Theory Of Crime And Policing Was Born, And Went Terribly Wrong

Shankar Vedantam

Chris Benderev

Renee Klahr

Maggie Penman

Jennifer Schmidt

The broken windows theory of policing suggested that cleaning up the visible signs of disorder — like graffiti, loitering, panhandling and prostitution — would prevent more serious crime as well. Getty Images/Image Source hide caption

The broken windows theory of policing suggested that cleaning up the visible signs of disorder — like graffiti, loitering, panhandling and prostitution — would prevent more serious crime as well.

In 1969, Philip Zimbardo, a psychologist from Stanford University, ran an interesting field study. He abandoned two cars in two very different places: one in a mostly poor, crime-ridden section of New York City, and the other in a fairly affluent neighborhood of Palo Alto, Calif. Both cars were left without license plates and parked with their hoods up.

After just 10 minutes, passersby in New York City began vandalizing the car. First they stripped it for parts. Then the random destruction began. Windows were smashed. The car was destroyed. But in Palo Alto, the other car remained untouched for more than a week.

Finally, Zimbardo did something unusual: He took a sledgehammer and gave the California car a smash. After that, passersby quickly ripped it apart, just as they'd done in New York.

This field study was a simple demonstration of how something that is clearly neglected can quickly become a target for vandals. But it eventually morphed into something far more than that. It became the basis for one of the most influential theories of crime and policing in America: "broken windows."

Thirteen years after the Zimbardo study, criminologists George L. Kelling and James Q. Wilson wrote an article for The Atlantic . They were fascinated by what had happened to Zimbardo's abandoned cars and thought the findings could be applied on a larger scale, to entire communities.

"The idea [is] that once disorder begins, it doesn't matter what the neighborhood is, things can begin to get out of control," Kelling tells Hidden Brain.

In the article, Kelling and Wilson suggested that a broken window or other visible signs of disorder or decay — think loitering, graffiti, prostitution or drug use — can send the signal that a neighborhood is uncared for. So, they thought, if police departments addressed those problems, maybe the bigger crimes wouldn't happen.

"Once you begin to deal with the small problems in neighborhoods, you begin to empower those neighborhoods," says Kelling. "People claim their public spaces, and the store owners extend their concerns to what happened on the streets. Communities get strengthened once order is restored or maintained, and it is that dynamic that helps to prevent crime."

Kelling and Wilson proposed that police departments change their focus. Instead of channeling most resources into solving major crimes, they should instead try to clean up the streets and maintain order — such as keeping people from smoking pot in public and cracking down on subway fare beaters.

The argument came at an opportune time, says Columbia University law professor Bernard Harcourt.

"This was a period of high crime, and high incarceration, and it seemed there was no way out of that dynamic. It seemed as if there was no way out of just filling prisons to address the crime problem."

An Idea Moves From The Ivory Tower To The Streets

As policymakers were scrambling for answers, a new mayor in New York City came to power offering a solution.

Rudy Giuliani won election in 1993, promising to reduce crime and clean up the streets. Very quickly, he adopted broken windows as his mantra.

It was one of those rare ideas that appealed to both sides of the aisle.

Conservatives liked the policy because it meant restoring order. Liberals liked it, Harcourt says, because it seemed like an enlightened way to prevent crime: "It seemed like a magical solution. It allowed everybody to find a way in their own mind to get rid of the panhandler, the guy sleeping on the street, the prostitute, the drugs, the litter, and it allowed liberals to do that while still feeling self-righteous and good about themselves."

Giuliani and his new police commissioner, William Bratton, focused first on cleaning up the subway system, where 250,000 people a day weren't paying their fare. They sent hundreds of police officers into the subways to crack down on turnstile jumpers and vandals.

Very quickly, they found confirmation for their theory. Going after petty crime led the police to violent criminals, says Kelling: "Not all fare beaters were criminals, but a lot of criminals were fare beaters. It turns out serious criminals are pretty busy. They commit minor offenses as well as major offenses."

The policy was quickly scaled up from the subway to the entire city of New York.

Police ramped up misdemeanor arrests for things like smoking marijuana in public, spraying graffiti and selling loose cigarettes. And almost instantly, they were able to trumpet their success. Crime was falling. The murder rate plummeted. It seemed like a miracle.

The media loved the story, and Giuliani cruised to re-election in 1997.

George Kelling and a colleague did follow-up research on broken windows policing and found what they believed was clear evidence of its success. In neighborhoods where there was a sharp increase in misdemeanor arrests — suggesting broken windows policing was in force — there was also a sharp decline in crime.

By 2001, broken windows had become one of Giuliani's greatest accomplishments. In his farewell address, he emphasized the beautiful and simple idea behind the success.

"The broken windows theory replaced the idea that we were too busy to pay attention to street-level prostitution, too busy to pay attention to panhandling, too busy to pay attention to graffiti," he said. "Well, you can't be too busy to pay attention to those things, because those are the things that underlie the problems of crime that you have in your society."

Questions Begin To Emerge About Broken Windows

Right from the start, there were signs something was wrong with the beautiful narrative.

"Crime was starting to go down in New York prior to the Giuliani election and prior to the implementation of broken windows policing," says Harcourt, the Columbia law professor. "And of course what we witnessed from that period, basically from about 1991, was that the crime in the country starts going down, and it's a remarkable drop in violent crime in this country. Now, what's so remarkable about it is how widespread it was."

Harcourt points out that crime dropped not only in New York, but in many other cities where nothing like broken windows policing was in place. In fact, crime even fell in parts of the country where police departments were mired in corruption scandals and largely viewed as dysfunctional, such as Los Angeles.

"Los Angeles is really interesting because Los Angeles was wracked with terrible policing problems during the whole time, and crime drops as much in Los Angeles as it does in New York," says Harcourt.

There were lots of theories to explain the nationwide decline in crime. Some said it was the growing economy or the end of the crack cocaine epidemic. Some criminologists credited harsher sentencing guidelines.

In 2006, Harcourt found the evidence supporting the broken windows theory might be flawed. He reviewed the study Kelling had conducted in 2001, and found the areas that saw the largest number of misdemeanor arrests also had the biggest drops in violent crime.

Harcourt says the earlier study failed to consider what's called a "reversion to the mean."

"It's something that a lot of investment bankers and investors know about because it's well-known and in the stock market," says Harcourt. "Basically, the idea is if something goes up a lot, it tends to go down a lot."

A graph in Kelling's 2001 paper is revealing. It shows the crime rate falling dramatically in the early 1990s. But this small view gives us a selective picture. Right before this decline came a spike in crime. And if you go further back, you see a series of spikes and declines. And each time, the bigger a spike, the bigger the decline that follows, as crime reverts to the mean.

Kelling acknowledges that broken windows may not have had a dramatic effect on crime. But he thinks it still has value.

"Even if broken windows did not have a substantial impact on crime, order is an end in itself in a cosmopolitan, diverse world," he says. "Strangers have to feel comfortable moving through communities for those communities to thrive. Order is an end in itself, and it doesn't need the justification of serious crime."

Order might be an end in itself, but it's worth noting that this was not the premise on which the broken windows theory was sold. It was advertised as an innovative way to control violent crime, not just a way to get panhandlers and prostitutes off the streets.

'Broken Windows' Morphs Into 'Stop And Frisk'

Harcourt says there was another big problem with broken windows.

"We immediately saw a sharp increase in complaints of police misconduct. Starting in 1993, what you're going to see is a tremendous amount of disorder that erupts as a result of broken windows policing, with complaints skyrocketing, with settlements of police misconduct cases skyrocketing, and of course with incidents, brutal incidents, all of a sudden happening at a faster and faster clip."

The problem intensified with a new practice that grew out of broken windows. It was called "stop and frisk," and was embraced in New York City after Mayor Michael Bloomberg won election in 2001.

If broken windows meant arresting people for misdemeanors in hopes of preventing more serious crimes, "stop and frisk" said, why even wait for the misdemeanor? Why not go ahead and stop, question and search anyone who looked suspicious?

There were high-profile cases where misdemeanor arrests or stopping and questioning did lead to information that helped solve much more serious crimes, even homicides. But there were many more cases where police stops turned up nothing. In 2008, police made nearly 250,000 stops in New York for what they called furtive movements. Only one-fifteenth of 1 percent of those turned up a gun.

Even more problematic, in order to be able to go after disorder, you have to be able to define it. Is it a trash bag covering a broken window? Teenagers on a street corner playing music too loudly?

In Chicago, the researchers Robert Sampson and Stephen Raudenbush analyzed what makes people perceive social disorder . They found that if two neighborhoods had exactly the same amount of graffiti and litter and loitering, people saw more disorder, more broken windows, in neighborhoods with more African-Americans.

George Kelling is not an advocate of stop and frisk. In fact, all the way back in 1982, he foresaw the possibility that giving police wide discretion could lead to abuse. In his article, he and James Q. Wilson write: "How do we ensure ... that the police do not become the agents of neighborhood bigotry? We can offer no wholly satisfactory answer to this important question."

In August of 2013, a federal district court found that New York City's stop and frisk policy was unconstitutional because of the way it singled out young black and Hispanic men. Later that year, New York elected its first liberal mayor in 20 years. Bill DeBlasio celebrated the end of stop and frisk. But he did not do away with broken windows. In fact, he re-appointed Rudy Giuliani's police commissioner, Bill Bratton.

And just seven months after taking over again as the head of the New York Police Department, Bratton's broken windows policy came under fresh scrutiny. The reason: the death of Eric Garner.

In July 2014, a bystander caught on cellphone video the deadly clash between New York City police officers and Garner, an African-American. After a verbal confrontation, officers tackled Garner, while restraining him with a chokehold, a practice that is banned in New York City.

Garner died not long after he was brought down to the ground. His death sparked massive protests, and his name is now synonymous with the distrust between police and African-American communities.

For George Kelling, this was not the end that he had hoped for. As a researcher, he's one of the few whose ideas have left the academy and spread like wildfire.

But once politicians and the media fell in love with his idea, they took it to places that he never intended and could not control.

"When, during the 1990s, I would occasionally read in a newspaper something like a new chief comes in and says, 'I'm going to implement broken windows tomorrow,' I would listen to that with dismay because [it's] a highly discretionary activity by police that needs extensive training, formal guidelines, constant monitoring and oversight. So do I worry about the implementation about broken windows? A whole lot ... because it can be done very badly."

In fact, Kelling says, it might be time to move away from the idea.

"It's to the point now where I wonder if we should back away from the metaphor of broken windows. We didn't know how powerful it was going to be. It simplified, it was easy to communicate, a lot of people got it as a result of the metaphor. It was attractive for a long time. But as you know, metaphors can wear out and become stale."

These days, the consensus among social scientists is that broken windows likely did have modest effects on crime. But few believe it caused the 60 or 70 percent decline in violent crime for which it was once credited.

And yet despite all the evidence, the idea continues to be popular.

Bernard Harcourt says there is a reason for that:

"It's a simple story that people can latch onto and that is a lot more pleasant to live with than the complexities of life. The fact is that crime dropped in America dramatically from the 1990s, and that there aren't really good, clean nationwide explanations for it."

The story of broken windows is a story of our fascination with easy fixes and seductive theories. Once an idea like that takes hold, it's nearly impossible to get the genie back in the bottle.

The Hidden Brain Podcast is hosted by Shankar Vedantam and produced by Maggie Penman, Jennifer Schmidt and Renee Klahr. Our supervising producer is Tara Boyle. You can also follow us on Twitter @hiddenbrain , and listen for Hidden Brain stories each week on your local public radio station.

- New York Police Department

- NYPD stop-and-frisk

- racial profiling

- broken windows

- hidden brain podcast

clock This article was published more than 4 years ago

How a 50-year-old study was misconstrued to create destructive broken-windows policing

The harmful policy was built on a shaky foundation.

2019 marked the 50th anniversary of a study that unwittingly contributed to the violent and racialized policing that dominates our criminal justice system today. In 1969, social psychologist Philip G. Zimbardo published research that became the basis for the controversial broken-windows theory of policing, which emerged in a 1982 Atlantic article penned by James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling. These two social scientists used the Zimbardo article as the sole empirical evidence for their theory, arguing, “If a window in a building is broken and is left unrepaired, all the rest of the windows will soon be broken.”

The problem? Wilson and Kelling distorted the study to suit their purposes. In short, the broken-windows theory was founded on a lie.

Even in the face of direct and damning challenges by the Movement for Black Lives and scholars of policing , the broken-windows theory has maintained its hold on police precincts across the nation. Most recently, broken windows has seen a resurgence in the subways of New York, where the Metropolitan Transportation Authority police doubled down on its assault against fare evasion.

By laying bare the fabrications at the foundation of the broken-windows theory, we can see what critics have long alleged and what those targeted by the policy have known to be true: By focusing on low-level offenses, this theory of policing works to criminalize communities of color and expand mass incarceration without making people safer.

This isn’t what Zimbardo set out to do. In the immediate wake of the 1960s urban uprisings, Zimbardo wanted to document the social causes of vandalism to disprove the conservative argument that it stemmed from individual or cultural pathology. His research team parked an Oldsmobile in the South Bronx and Palo Alto, Calif., surveilling the cars for days. Zimbardo hypothesized that the informal economies of the Bronx would make quick work of the car.

He was right.

Although the research team was surprised that the first “vandals” were not youths of color but, rather, a white, “well-dressed” family, Zimbardo considered his basic hypothesis confirmed: The lack of community cohesion in the Bronx produced a sense of “anonymity,” which in turn generated vandalism. He concluded, “Conditions that create social inequality and put some people outside of the conventional reward structure of the society make them indifferent to its sanctions, laws, and implicit norms.”

The Palo Alto Oldsmobile, in contrast, went untouched. After a week-long, unremarkable stakeout, Zimbardo drove the car to the Stanford campus, where his research team aimed to “prime” vandalism by taking a sledgehammer to its windows. Upon discovering that this was “stimulating and pleasurable,” Zimbardo and his graduate students “got carried away.” As Zimbardo described it, “One student jumped on the roof and began stomping it in, two were pulling the door from its hinges, another hammered away at the hood and motor, while the last one broke all the glass he could find.” The passersby the study had intended to observe had turned into spectators and only joined in after the car was already wrecked.

Zimbardo’s conclusions were the stuff of liberal criminology: Anyone — even Stanford researchers! — could be lured into vandalism, and this was particularly true in places like the Bronx with heightened social inequalities. For Zimbardo, what happened in the Bronx and at Stanford suggested that crowd mentality, social inequalities and community anonymity could prompt “good citizens” to act destructively. This was no radical critique; it was an indictment of law-and-order politics that viewed vandalism as a senseless, unpardonable act. In a line that could have been lifted directly out of the countless “riot reports” published in the late 1960s, Zimbardo asserted, “Vandalism is a rebellion with a cause.”

Zimbardo’s study claimed little immediate impact outside academic circles. Almost 15 years later, Wilson and Kelling gave it new life, building their broken-windows theory atop a fundamental misrepresentation of Zimbardo’s experiment. In Wilson and Kelling’s account, Zimbardo’s experiment proved that “one unrepaired broken window is a signal that no one cares, and so breaking more windows costs nothing.”

Their misleading recap of Zimbardo’s study not only conflated the Stanford and Palo Alto experiments but also so distorted the order of events that it routed readers away from Zimbardo’s conclusions. In their version, “the car in Palo Alto sat untouched for more than a week. Then Zimbardo smashed part of it with a sledgehammer. Soon, passersby were joining in.” What they conveniently neglected to mention was that the researchers themselves had laid waste to the car.

By omitting this crucial detail, Wilson and Kelling manipulated Zimbardo’s experiment to draw a straight line between one broken window and “a thousand broken windows.” This enabled them to claim that all it took was a broken window to transform “staid” Palo Alto into the Bronx, where “no one car[ed].” The problem is, it wasn’t a broken window that enticed onlookers to join the fray; it was the spectacle of faculty and students destroying an Oldsmobile in the middle of Stanford’s campus. In place of Zimbardo’s critique of inequality and anonymity, Wilson and Kelling had invented a broken window and invested it with the ability to spur vandalism.

Why would Wilson and Kelling go through the trouble of introducing Zimbardo’s study only to misrepresent it? Because what they got out of the study was not its empirical evidence, but the evocative, racialized image of the Bronx’s broken windows, which had already been drilled into the national psyche.

During the 1970s, journalists frequently invoked the South Bronx as “the American urban problem in microcosm,” in the words of one New York Times article. These reports about the Bronx featured photographs of empty-eyed tenements and opened with lines like “abandoned buildings, with smoke stains flaring up from their blind and broken windows.” Media outlets thereby weaponized the broken windows of the Bronx as a symbol of urban and racial degeneration.

So potent and “unnerving” was the symbol of the broken window that one of the few municipal housing initiatives in the early-1980s Bronx was devoted to papering over empty window frames that faced commuters on the Cross Bronx Expressway. The vinyl decals the city installed depicted “a lived-in look of curtains, shades, shutters and flowerpots.”

It was the symbol of the “unnerving” broken window that Wilson and Kelling sought to fold into their theory. In their telling, the Bronx’s “thousand broken windows” were juxtaposed with Palo Alto’s one. For them, the danger was proliferation — the creation of many Bronxes — through small signs of disorder. The racist subtext rang loud and clear. Citing Zimbardo’s experiment allowed Wilson and Kelling to sound alarms over the possibility that all cities would go the way of the Bronx if they didn’t embrace their new regime of policing. What was missing, of course, was Zimbardo’s restrained, but resolute, focus on structural causation and systemic inequality.

By exploiting this set of fears and meanings, the broken-windows theory gained currency in policy circles and police precincts across the nation and globe. Accordingly, to “ dislodge this boulder ,” in the words of prison abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore, we need to challenge its intellectual foundations head-on. The movement against this criminological cockroach has largely drawn attention to the violence that broken windows policing has inflicted on communities of color. This is urgent and essential work, which can be bolstered by the project of exposing and then obliterating the shaky intellectual ground upon which it stands.

From its origins to its ruinous rise, the broken-windows theory was just that — broken. It’s time to tear it down.

What Is the Broken Windows Theory?

- Equal Rights

- The U. S. Government

- U.S. Foreign Policy

- U.S. Liberal Politics

- U.S. Conservative Politics

- Women's Issues

- The Middle East

- Race Relations

- Immigration

- Crime & Punishment

- Canadian Government

- Understanding Types of Government

- B.S., Texas A&M University

The broken windows theory states that visible signs of crime in urban areas lead to further crime. The theory is often associated with the 2000 case of Illinois v. Wardlow , in which the U.S. Supreme Court confirmed that the police, based on the legal doctrine of probable cause , have the authority to detain and physically search, or “stop-and-frisk,” people in crime-prone neighborhoods who appear to be behaving suspiciously.

Key Takeaways: Broken Windows Theory

- The broken windows theory of criminology holds that visible signs of crime in densely-populated, lower-income urban areas will encourage additional criminal activity.

- Broken windows neighborhood policing tactics employ heightened enforcement of relatively minor “quality of life” crimes like loitering, public drinking, and graffiti.

- The theory has been criticized for encouraging discriminatory police practices, such as unequal enforcement based on racial profiling.

Broken Windows Theory Definition

In the field of criminology, the broken windows theory holds that lingering visible evidence of crime, anti-social behavior, and civil unrest in densely populated urban areas suggests a lack of active local law enforcement and encourages people to commit further, even more serious crimes.

The theory was first suggested in 1982 by social scientist, George L. Kelling in his article, “Broken Windows: The police and neighborhood safety” published in The Atlantic. Kelling explained the theory as follows:

“Consider a building with a few broken windows. If the windows are not repaired, the tendency is for vandals to break a few more windows. Eventually, they may even break into the building, and if it's unoccupied, perhaps become squatters or light fires inside.

“Or consider a pavement. Some litter accumulates. Soon, more litter accumulates. Eventually, people even start leaving bags of refuse from take-out restaurants there or even break into cars.”

Kelling based his theory on the results of an experiment conducted by Stanford psychologist Philip Zimbardo in 1969. In his experiment, Zimbardo parked an apparently disabled and abandoned car in a low-income area of the Bronx, New York City, and a similar car in an affluent Palo Alto, California neighborhood. Within 24 hours, everything of value had been stolen from the car in the Bronx. Within a few days, vandals had smashed the car’s windows and ripped out the upholstery. At the same time, the car abandoned in Palo Alto remained untouched for over a week, until Zimbardo himself smashed it with a sledgehammer. Soon, other people Zimbardo described as mostly well dressed, “clean-cut” Caucasians joined in the vandalism. Zimbardo concluded that in high-crime areas like the Bronx, where such abandoned property is commonplace, vandalism and theft occur far faster as the community takes such acts for granted. However, similar crimes can occur in any community when the people’s mutual regard for proper civil behavior is lowered by actions that suggest a general lack of concern.

Kelling concluded that by selectively targeting minor crimes like vandalism, public intoxication, and loitering, police can establish an atmosphere of civil order and lawfulness, thus helping to prevent more serious crimes.

Broken Windows Policing

In1993, New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani and police commissioner William Bratton cited Kelling and his broken windows theory as a basis for implementing a new “tough-stance” policy aggressively addressing relatively minor crimes seen as negatively affecting the quality of life in the inner-city.

Bratton directed NYPD to step up enforcement of laws against crimes like public drinking, public urination, and graffiti. He also cracked down on so-called “squeegee men,” vagrants who aggressively demand payment at traffic stops for unsolicited car window washings. Reviving a Prohibition-era city ban on dancing in unlicensed establishments, police controversially shuttered many of the city’s night clubs with records of public disturbances.

While studies of New York’s crime statistics conducted between 2001 and 2017 suggested that enforcement policies based on the broken windows theory were effective in reducing rates of both minor and serious crimes, other factors may have also contributed to the result. For example, New York’s crime decrease may have simply been part of a nationwide trend that saw other major cities with different policing practices experience similar decreases over the period. In addition, New York City’s 39% drop in the unemployment rate could have contributed to the reduction in crime.

In 2005, police in the Boston suburb of Lowell, Massachusetts, identified 34 “crime hot spots” fitting the broken windows theory profile. In 17 of the spots, police made more misdemeanor arrests, while other city authorities cleared trash, fixed streetlights, and enforced building codes. In the other 17 spots, no changes in routine procedures were made. While the areas given special attention saw a 20% reduction in police calls, a study of the experiment concluded that simply cleaning up the physical environment had been more effective than an increase in misdemeanor arrests.

Today, however, five major U.S. cities—New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Boston, and Denver—all acknowledge employing at least some neighborhood policing tactics based on Kelling’s broken windows theory. In all of these cities, police stress aggressive enforcement of minor misdemeanor laws.

Despite its popularity in major cities, police policy based on the broken windows theory is not without its critics, who question both its effectiveness and fairness of application.

In 2005, University of Chicago Law School professor Bernard Harcourt published a study finding no evidence that broken windows policing actually reduces crime. “We don’t deny that the ‘broken windows’ idea seems compelling,” wrote Harcourt. “The problem is that it doesn’t seem to work as claimed in practice.”

Specifically, Harcourt contended that crime data from New York City’s 1990s application of broken windows policing had been misinterpreted. Though the NYPD had realized greatly reduced crime rates in the broken windows enforcement areas, the same areas had also been the areas worst affected by the crack-cocaine epidemic that caused citywide homicide rates to soar. “Everywhere crime skyrocketed as a result of crack, there were eventual declines once the crack epidemic ebbed,” Harcourt note. “This is true for police precincts in New York and for cities across the country.” In short, Harcourt contended that New York’s declines in crime during the 1990s were both predictable and would have happened with or without broken windows policing.

Harcourt concluded that for most cities, the costs of broken windows policing outweigh the benefits. “In our opinion, focusing on minor misdemeanors is a diversion of valuable police funding and time from what really seems to help—targeted police patrols against violence, gang activity and gun crimes in the highest-crime ‘hot spots.’”

Broken windows policing has also been criticized for its potential to encourage unequal, potentially discriminatory enforcement practices such as racial profiling , too often with disastrous results.

Arising from objections to practices like “Stop-and-Frisk,” critics point to the case of Eric Garner, an unarmed Black man killed by a New York City police officer in 2014. After observing Garner standing on a street corner in a high-crime area of Staten Island, police suspected him of selling “loosies,” untaxed cigarettes. When, according to the police report, Garner resisted arrest, an officer took him to the ground in a chock hold. An hour later, Garner died in the hospital of what the coroner determined to be homicide resulting from, “Compression of neck, compression of chest and prone positioning during physical restraint by police.” After a grand jury failed to indict the officer involved, anti-police protests broke out in several cities.

Since then, and due to the deaths of other unarmed Black men accused of minor crimes predominantly by white police officers, more sociologists and criminologists have questioned the effects of broken windows theory policing. Critics argue that it is racially discriminatory, as police statistically tend to view, and thus, target, non-whites as suspects in low-income, high-crime areas.

According to Paul Larkin, Senior Legal Research Fellow at the Heritage Foundation, established historic evidence shows that persons of color are more likely than whites to be detained, questioned, searched, and arrested by police. Larkin suggests that this happens more often in areas chosen for broken windows-based policing due to a combination of: the individual’s race, police officers being tempted to stop minority suspects because they statistically appear to commit more crimes, and the tacit approval of those practices by police officials.

Sources and Further Reference

- Wilson, James Q; Kelling, George L (Mar 1982), “ Broken Windows: The police and neighborhood safety .” The Atlantic.

- Harcourt, Bernard E. “ Broken Windows: New Evidence from New York City & a Five-City Social Experiment .” University of Chicago Law Review (June 2005).

- Fagan, Jeffrey and Davies, Garth. “ Street Stops and Broken Windows .” Fordham Urban Law Journal (2000).

- Taibbi, Matt. “ The Lessons of the Eric Garner Case .” Rolling Stone (November 2018).

- Herbert, Steve; Brown, Elizabeth (September 2006). “ Conceptions of Space and Crime in the Punitive Neoliberal City .” Antipode.

- Larkin, Paul. “ Flight, Race, and Terry Stops: Commonwealth v.Warren .” The Heritage Foundation.

- Criminology Definition and History

- How the Illinois v. Wardlow Case Affects Policing

- The History of Modern Policing

- What Is a Criminal Infraction?

- 5 Common Misconceptions About Black Lives Matter

- What Is Restorative Justice?

- Why Racial Profiling Is a Bad Idea

- What Is Retributive Justice?

- Racial Profiling and Why it Hurts Minorities

- An Overview of Labeling Theory

- What Is Procedural Justice?

- Terry v. Ohio: Supreme Court Case, Arguments, Impact

- Racial Bias and Discrimination: From Colorism to Racial Profiling

- Manifest Function, Latent Function, and Dysfunction in Sociology

- What Is Social Learning Theory?

- What's the Difference Between Probation and Parole?

How a 50-Year-Old Study Was Misconstrued to Create Destructive Broken-Windows Policing

2019 marked the 50th anniversary of a study that unwittingly contributed to the violent and racialized policing that dominates our criminal justice system today. In 1969, social psychologist Philip G. Zimbardo published research that became the basis for the controversial broken-windows theory of policing, which emerged in a 1982 Atlantic article penned by James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling. These two social scientists used the Zimbardo article as the sole empirical evidence for their theory, arguing, “If a window in a building is broken and is left unrepaired, all the rest of the windows will soon be broken.”

The problem? Wilson and Kelling distorted the study to suit their purposes. In short, the broken-windows theory was founded on a lie.

Even in the face of direct and damning challenges by the Movement for Black Lives and scholars of policing , the broken-windows theory has maintained its hold on police precincts across the nation. Most recently, broken windows has seen a resurgence in the subways of New York, where the Metropolitan Transportation Authority police doubled down on its assault against fare evasion.

By laying bare the fabrications at the foundation of the broken-windows theory, we can see what critics have long alleged and what those targeted by the policy have known to be true: By focusing on low-level offenses, this theory of policing works to criminalize communities of color and expand mass incarceration without making people safer.

This isn’t what Zimbardo set out to do. In the immediate wake of the 1960s urban uprisings, Zimbardo wanted to document the social causes of vandalism to disprove the conservative argument that it stemmed from individual or cultural pathology. His research team parked an Oldsmobile in the South Bronx and Palo Alto, Calif., surveilling the cars for days. Zimbardo hypothesized that the informal economies of the Bronx would make quick work of the car.

He was right.

Although the research team was surprised that the first “vandals” were not youths of color but, rather, a white, “well-dressed” family, Zimbardo considered his basic hypothesis confirmed: The lack of community cohesion in the Bronx produced a sense of “anonymity,” which in turn generated vandalism. He concluded, “Conditions that create social inequality and put some people outside of the conventional reward structure of the society make them indifferent to its sanctions, laws, and implicit norms.”

The Palo Alto Oldsmobile, in contrast, went untouched. After a week-long, unremarkable stakeout, Zimbardo drove the car to the Stanford campus, where his research team aimed to “prime” vandalism by taking a sledgehammer to its windows. Upon discovering that this was “stimulating and pleasurable,” Zimbardo and his graduate students “got carried away.” As Zimbardo described it, “One student jumped on the roof and began stomping it in, two were pulling the door from its hinges, another hammered away at the hood and motor, while the last one broke all the glass he could find.” The passersby the study had intended to observe had turned into spectators and only joined in after the car was already wrecked.

Zimbardo’s conclusions were the stuff of liberal criminology: Anyone — even Stanford researchers! — could be lured into vandalism, and this was particularly true in places like the Bronx with heightened social inequalities. For Zimbardo, what happened in the Bronx and at Stanford suggested that crowd mentality, social inequalities and community anonymity could prompt “good citizens” to act destructively. This was no radical critique; it was an indictment of law-and-order politics that viewed vandalism as a senseless, unpardonable act. In a line that could have been lifted directly out of the countless “riot reports” published in the late 1960s, Zimbardo asserted, “Vandalism is a rebellion with a cause.”

Zimbardo’s study claimed little immediate impact outside academic circles. Almost 15 years later, Wilson and Kelling gave it new life, building their broken-windows theory atop a fundamental misrepresentation of Zimbardo’s experiment. In Wilson and Kelling’s account, Zimbardo’s experiment proved that “one unrepaired broken window is a signal that no one cares, and so breaking more windows costs nothing.”

Their misleading recap of Zimbardo’s study not only conflated the Stanford and Palo Alto experiments but also so distorted the order of events that it routed readers away from Zimbardo’s conclusions. In their version, “the car in Palo Alto sat untouched for more than a week. Then Zimbardo smashed part of it with a sledgehammer. Soon, passersby were joining in.” What they conveniently neglected to mention was that the researchers themselves had laid waste to the car.

By omitting this crucial detail, Wilson and Kelling manipulated Zimbardo’s experiment to draw a straight line between one broken window and “a thousand broken windows.” This enabled them to claim that all it took was a broken window to transform “staid” Palo Alto into the Bronx, where “no one car[ed].” The problem is, it wasn’t a broken window that enticed onlookers to join the fray; it was the spectacle of faculty and students destroying an Oldsmobile in the middle of Stanford’s campus. In place of Zimbardo’s critique of inequality and anonymity, Wilson and Kelling had invented a broken window and invested it with the ability to spur vandalism.

Why would Wilson and Kelling go through the trouble of introducing Zimbardo’s study only to misrepresent it? Because what they got out of the study was not its empirical evidence, but the evocative, racialized image of the Bronx’s broken windows, which had already been drilled into the national psyche.

During the 1970s, journalists frequently invoked the South Bronx as “the American urban problem in microcosm,” in the words of one New York Times article. These reports about the Bronx featured photographs of empty-eyed tenements and opened with lines like “abandoned buildings, with smoke stains flaring up from their blind and broken windows.” Media outlets thereby weaponized the broken windows of the Bronx as a symbol of urban and racial degeneration.

So potent and “unnerving” was the symbol of the broken window that one of the few municipal housing initiatives in the early-1980s Bronx was devoted to papering over empty window frames that faced commuters on the Cross Bronx Expressway. The vinyl decals the city installed depicted “a lived-in look of curtains, shades, shutters and flowerpots.”

It was the symbol of the “unnerving” broken window that Wilson and Kelling sought to fold into their theory. In their telling, the Bronx’s “thousand broken windows” were juxtaposed with Palo Alto’s one. For them, the danger was proliferation — the creation of many Bronxes — through small signs of disorder. The racist subtext rang loud and clear. Citing Zimbardo’s experiment allowed Wilson and Kelling to sound alarms over the possibility that all cities would go the way of the Bronx if they didn’t embrace their new regime of policing. What was missing, of course, was Zimbardo’s restrained, but resolute, focus on structural causation and systemic inequality.

By exploiting this set of fears and meanings, the broken-windows theory gained currency in policy circles and police precincts across the nation and globe. Accordingly, to “ dislodge this boulder ,” in the words of prison abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore, we need to challenge its intellectual foundations head-on. The movement against this criminological cockroach has largely drawn attention to the violence that broken windows policing has inflicted on communities of color. This is urgent and essential work, which can be bolstered by the project of exposing and then obliterating the shaky intellectual ground upon which it stands.

From its origins to its ruinous rise, the broken-windows theory was just that — broken. It’s time to tear it down.

Broken Windows Thesis

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 27 November 2018

- Cite this reference work entry

- Joshua C. Hinkle 5

1097 Accesses

3 Citations

Incivilities thesis ; Order maintenance

Few ideas in criminology have had the type of direct impact on criminal justice policy exhibited by the broken windows thesis. From its inauspicious beginnings in a nine-page article by James Q. Wilson and George Kelling in The Atlantic Monthly , the broken windows thesis has impacted policing strategies around the world. From the “quality of life policing” efforts in New York City (Kelling and Sousa 2001 ) to “Zero Tolerance” policing in England (Dennis and Mallon 1998 ), police agencies around the world have embraced Wilson and Kelling’s idea that focusing on less serious offenses can yield important benefits in terms of community safety and prevention of more serious crime. Despite this broad policy influence, research on the theory itself has been relatively weak and has produced equivocal findings as will be detailed in this entry.